50 Years Ago: Hopi’s lawyer hits pot of gold

Hopi Tribe logo.

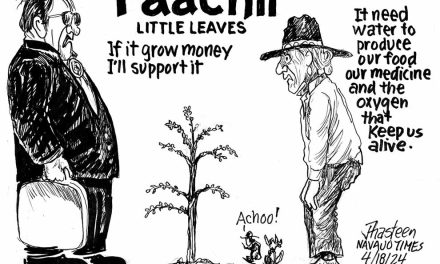

There had been a lot of stories over the past two years in the paper about Robert Littell, the general counsel of the Navajo Tribe who had come under attack for his efforts to convince the Navajo Tribal Council to accept a lawsuit from the Hopis over some 1.8 million acres of land in the western portion of the reservation that was occupied almost entirely by Navajo families.

The Navajos did not have to accept the suit and could have just cited sovereign immunity and the dispute would basically have been over but Littell convinced the tribe to accept the suit because he believed it would have resulted in the Navajos winning and getting clear title to the land.

But what was going on inside the Hopi government?

Word came out near the end of November 1964 that the Hopi government was so happy at the efforts of their Utah attorney, John Boyden, that they agreed to pay him almost $1 million, the highest award given to any tribal attorney up to this point.

The Hopi Council said $778,000 was for legal fees and $220,000 was in appreciation for “taking the case when no one else would.”

This came in response to a decision by a federal district court in 1963 to give the Hopis clear title to 631,000 acres and one-half interest to another 1.8 million acres.

The victory, said Boyden, was “a wonderful opportunity for a wonderful group of people.

Boyden pointed out that the value of the land given to the Hopis by the court decision was in excess of $38 million.

He also explained that the dispute between the two tribes had been going on for more than 26 years and he had received almost no money from the tribe during the years of the land dispute because “the tribe had no money” which required him to pay most of the court costs and fees himself.

Since that court decision, things had turned around for the Hopis, who received a $3 million bonus from oil companies who received permission to drill on Hopi land.

The money to pay Boyden will come from these funds. Boyden said he plans to split the Hopi monies with two of his associates who worked with him on the case — Allen Tibbals and Bryan Croft.

Littell was making about $35,000 from the tribe but later, in the 1970s, he threatened to sue the tribe if its government did not give him a big amount of money as well because of his contract as general counsel, which gave him 10 percent of the value of anything he acquired for the tribe.

He claimed that the tribe received rights to half the disputed land and therefore he should get 10 percent of the value of that land. The Navajo Tribe reportedly backed down and reached a settlement with him that netted him several hundred thousand dollars.

Back in 1964, there were thousands of Navajos who were employed annually as migrant farm laborers, leaving the reservation for months at a time and going to California and other states to work on farms during the planting and harvesting season.

Like Navajos who traveled most of the year working for the railroads, Navajo migrant workers were usually ignored by the tribal government, in part because no one knew just how many Navajos were doing it and whether they were being treated fairly.

But tribal leaders under Raymond Nakai hoped to change this, which is why they agreed to support Victor C. Uchendu, a graduate student at Northwest University in Illinois who approached Nakai for help in his research on Navajo migrant workers.

“His work is of comparative research as he has already done much work and studies among his own people in Nigeria, West Africa,” the Navajo Times said in a front-page article.

Uchendu has a bachelor’s degree in economics and a master’s degree in anthropology, which he says he wants to use to look not only at the numbers of Navajos who are part of this industry but also to look at their lifestyle and how well they are treated by their employers.

Stories that have been published by the Times over the years has shown it to be a fairly harsh lifestyle from the low payment and reports of abuse by farmers who hire them to help bring in their crops.

In other news, Nakai journeyed to Greasewood some 22 miles southwest of Ganado where dedication services were held for the new boarding house, which included four new 160-pupil dormitories, an academic building with 23 classrooms, a library and a new dining room and kitchen.

There were also 52 new two- and three-bedroom houses, 20 new efficiency apartments and a fire station. The school has 600 students as well as 50 day students.

“This is one more step towards the progress of getting in line with my aim to seat every Navajo child eligible to attend a government school on the reservation,” he said, adding that he planned to speak at a number of other school dedications since the Bureau of Indian Affairs was in the midst of building several more in and around the Navajo Reservation.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow