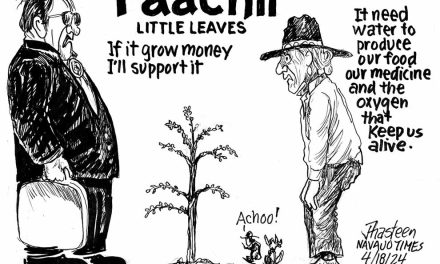

Drawing humor: A conversation with cartoonist Jack Ahasteen

By Rhiannon Koehler

Special to the Times

CHICAGO

Cartoonist Jack Ahasteen of the Navajo Times is not a fan of notoriety. In fact, during the most contentious days of the Navajo-Hopi Land Dispute, he often didn’t sign his own cartoons.

Navajo Times | File

Jack Ahasteen has been drawing cartoons for the Navajo Times for many years.

“I didn’t want to be in the limelight,” he says. “I don’t want to be in the public, but somehow the word got out…” Despite Ahasteen’s best efforts, a measure of fame has found him. Sometimes strangers will even approach his grown daughters in Phoenix, inquiring about Ahasteen. He says, “They say, ‘You know, whenever we introduce ourselves to somebody, they recognize our last name.

And they want to know if this is your dad that’s doing (all these) cartoons(s).”

Ahasteen’s work stands out for its unflinching representations of life in the Four Corners region and, specifically, the reality of the injustice of Diné forced removal.

It’s an issue that hits close to home. Ahasteen’s own family faced forced removal from their ancestral home at the hands of U.S. officials. “Right where that land was divided up, it was where I was born,” he said. “I wasn’t born in the hospital.” Facing relocation was traumatic, Ahasteen says, especially for elders who didn’t speak English and therefore couldn’t understand what United States officials were telling them.

“They didn’t understand what the laws are, or what was going on,” Ahasteen remembers, noting that he was getting most of the information about relocation and range wars from the Navajo Times that he read each week while studying at Arizona State University.

“So really, I used to always tell my parents in a humorous way what was going on and they would just laugh about it,” he said. “And that’s where I got the ideas, how to draw cartoons and stuff like that…I had to draw these cartoons in a way they could understand it.”

Showcased on front page

Soon, Ahasteen’s work became known to the Navajo Times. Even before he had an official job with the paper, his work was being showcased on the front page. “(Back then) they didn’t have computers, to do the layout and stuff like that,” he recalled. “They had an old-fashioned way of doing it, using wax and pasting it onto a sheet.

“And sometimes they would have a space that I started (drawing in),” he said. “(They’d just) tell me to scribble something on there, a graphic illustration. Then, pretty soon, people wanted me to do some cartoons. (They’d say) ‘Can you draw a cartoon?’”

Of course, Ahasteen wasn’t the only cartoonist drawing editorial cartoons related to the Navajo-Hopi Land Dispute. He followed Clare Thompson, who passed away in December 1974, and he was producing work at the same time as Philip Sekaquaptewa, the Hopi cartoonist with Qua’Toqti. Soon, a conversation between the two developed, taking place entirely in images.

“I could read the Hopi newspaper,” Ahasteen remembers, “And I would create something (in response to their cartoons), kind of like copying something that they said or something that they done (sic), and put it back in there.”

The cartoons that were created as a result gave voice to the trauma of forced removal. As Ahasteen remarked in a 2019 Navajo Times front-page article written by Rima Krisst, “There’s no word for relocation in Navajo. It was like a death sentence to them.”

The breakdown in communication between officials enacting removal and the Diné who experienced it was worse than most people knew. As Ahasteen says, in Diné cosmology death is explained as your spirit going away, over the hill, and not coming back.

“That’s a process of a funeral,” he said, “when they have somebody that leave this world. That’s what they usually say. Just go over the hill, don’t come back. Wherever the spirit goes, they tell them and encourage them to don’t look back at the school or the hill, and don’t come back.”

When it came to relocation, officials who spoke zero Navajo and often failed to bring translators with them to conversations with Diné people managed to transmit the expectation to traditional elders that relocation meant moving away, over the hill, and not coming back. “Actually you’re told to die and don’t come back,” Ahasteen says.

A ‘better life’

For many people, including second-generation relocatees, any government offers regarding relocation assistance, housing assistance, or funding paled in comparison to the reality of leaving.

For Ahasteen’s family, relocation from Window Rock was accompanied by empty promises. As he originally told Krisst of the Navajo Times: “The federal government promised us, ‘You’re going to have a better life. That ‘better life’ might come with a house boasting new amenities, but it meant leaving behind land, livestock, and traditional lifeways.”

Ahasteen, seeing the sorrow of his parents and his community, knew that there had to be a better way to survive. He reflects on the reality of the value of people’s lives being rejected by officials tasked with relocating thousands of people.

“What is it going to do (to you) when you’re told to leave this world?” he asks. There’s no answers, only loose ends. Still, Ahasteen believes, “There has to be some kind of humor for them to understand that you can still be happy. You can still smile.”

Editorial cartoons, during and after the dispute, proved to be a balm to the open wound. Still the historical trauma of relocation persists to this day. In the cartoons that Ahasteen published with the Navajo Times in the years following partition the emotional scars are drawn as physical wounds.

In “After the dust settle,” originally published on Feb. 16, 2005, Ahasteen presents two battered and beleaguered men representing the Hopi and Diné nations. The dust includes all of the harms of the past hundred years: relocation, job loss, religious desegregation, loss (of) revenue, and livestock reduction.

Barbed wire remains

The fences between the Hopi and Diné stand, their sharp barbed wire a reminder of the thorns in the relationship that still exists. For Ahasteen, it isn’t over. The past isn’t the past. As he notes, “One of my daughters who is always tuned into people, she has health issues, and she’s always saying that I’ve been traumatized by this. What do you do? “Their grandparents, what they had to go through,” he said. “How to cope with all of this stuff? It goes back to that, but for me it’s like…”

It’s clear exactly what he means. Ahasteen clears his throat and notes, “I wish these reporters, some of these reporters, (that I’d) told them about it. What does historical trauma do?”

For many people in the region, Ahasteen’s cartoons themselves have become a guide for how to survive. In fact, Ahasteen found out through a reporter that there was a hogan literally wallpapered with his art in what was then known as the Joint-Use Area. Now, Ahasteen continues serving as a guide for his community.

“I just focus on the cartoons,” he says. He even brings cartooning to his other endeavors. Sometimes, for example, he helps out one of his daughters at her bakery, illustrating cakes so that they transform into edible works of art. And sometimes he holds public conversations about his role as a cartoonist, about forced relocation, and about the range wars.

He’s a photographer too, and often takes photos that, like his cartoons, build important linguistic and cultural bridges.

Continuing the conversation

Ahasteen believes that continuing the conversation is important. The second generation, as he knows first-hand, is often only exposed to the reality of the dispute through his work. “They (second-generation relocates) come up to me and say, ‘We didn’t know nothing about all this stuff that happened until we saw that cartoon,’” Ahasteen says. “And they get emotional about it and they want to be a part of it,” he said.

Thinking of ways to heal, and the people who have experienced relocation and passed on, Ahasteen says, “We can create a memorial for them, or something. “We keep telling them, ‘You had great grandparents that fought all of this.They were talking about all this relocation. You still need to talk about that because they left. But they prayed for you. That’s why you’re here. They prayed that one day (their) grandkids are going to live in this world and they can continue their legacies,’” he said.

The fight goes on. But Ahasteen would rather laugh than succumb to weariness. After all, the joy, the humor, and the community that defines his cartoons can’t ever be taken away from Diné people who are protecting their traditions and fighting injustice. That, at least, is theirs to keep.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow