Proving himself

Diné elder gets birth certificate at age 74

By Cindy Yurth

Tséyi' Bureau

CORRALES, N.M., June 17, 2011

(Times photo - Cindy Yurth)

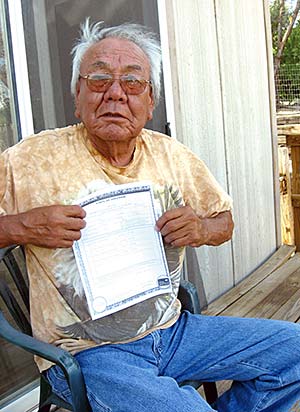

On his front porch in Corrales, N.M., Eric "Ed" Camron poses with his newly acquired birth certificate.

Just don't get him started on it. "The whole thing is dumber than pig s__t," Camron said. "I don't even want to talk about it."

But, after a little coaxing on a pleasant afternoon on his front porch in this horsey hamlet just west of Albuquerque, he did.

Camron, who is Tsi'naajinii (Black Streak Wood Clan), born for Tábaahá (Edge Water Clan), was born in his family hogan in Klagetoh, Ariz., on Feb. 9, 1937. Or so everyone always told him.

He got through 74 years, and a tour in the military, without having to prove it to anyone.

Then, four years ago, his commercial driver's license expired.

A semi-retired lineman, Camron had had a CDL for decades. Linemen occasionally need to drive big rigs that require one. If you're on the union's on-call list, as Camron is, not having a CDL makes you that much less desirable.

Camron did what he had always done when his license expired: he took it to the New Mexico Motor Vehicle Division to get it renewed.

That's when he encountered a new rule, courtesy of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security: To get a CDL, you now have to produce an original copy of your birth certificate.

Like many Navajo elders, Camron didn't have a birth certificate.

"The medicine man didn't give me one," he quipped.

The DMV was not amused. They instructed Camron to go to Arizona and apply for a delayed certificate of birth.

Four years and about a thousand dollars later, he has it. The process, according to Camron's wife Joyce Fay, was "like an extended scavenger hunt."

Fay encouraged Camron to share his story in case it helps other Navajo elders brave the process.

Long slog

The first step is to call the Arizona Department of Vital Records and order an application packet. (New Mexico and Utah each have a similar department and application.)

Then you have to go through a rather involved process of proving you don't, in fact, have a birth certificate (why you would undergo this ordeal if you already had one is not explained).

This involves a month or two of relying on a series of public servants who, according to Fay and Camron, don't much care whether you get your birth certificate or not.

Eventually, you get a letter stating what you already know: that you don't have a birth certificate. Then you can start the actual application process.

This involves a hunt for a variety of suggested documents. The application does not say how many you have to have or which ones are better, only that they will examine them and decide your fate on a case-by-case basis.

Most of the suggested documents seem to have little to do with when and where you were born, like applications for employment or insurance policies.

One shortcut is an affidavit from someone who witnessed the birth. But they have to be 10 years older than you, and in a traditional Diné situation, it's quite possible the only person to witness the birth was your mother and possibly a female relative.

"I'm 74 years old," Camron said. "Who's around to sign for me?"

So the hunt was on. But there were many twists and turns, and they soon found that recordkeeping on the Navajo Nation in the 1930s and '40s was ... well, to call it spotty would be the understatement of the year.

"For a few years, he just gave up," Fay said. "I can see why it made him mad. It would make me mad, as an Anglo. But to be Native American and not be able to prove you were born in America, that's just crazy."

"If it weren't for Joyce, I wouldn't have this," said Camron, waving his brand new birth certificate. "She's my lawyer, my banker, my everything."

The couple restarted the process a few months ago, after Fay got tired of hearing Camron complaining about not being able to work.

"Let's just get this done," she suggested. "If you take it all at once, it seems impossible, but if we go through it step by step, we can do it."

They contacted former state Rep. Albert Tom, a fellow Klagetoh native who had helped many Navajo elders get their documents when he was in office. Tom referred them to his former secretary, Kat Clark, who advised the couple to look for "the green paper and the yellow paper" in Camron's tribal census documents.

That turned out to be the Certificate of Indian Blood and something called an "affidavit of birth," with an official tribal stamp.

"I was surprised when I saw that," said Fay. "If your tribe says you were born on the reservation, shouldn't that be enough?"

More proof needed

But it wasn't. They looked through the other suggestions from the state: military discharge papers, life insurance policy, elementary school records, employment application, U.S. passport (which you can't get without a birth certificate), marriage license, an original application for a Social Security card (the card itself doesn't count) and proof of mother's residency.

Camron had some of the suggested records, but there was a glitch. Like many Diné, he had gone by several different names during his lifetime. In 1981, for personal reasons, he had officially changed his name from Edward Curley to Eric Camron (although people continued to call him "Ed").

Then it turned out that his baptismal record was in yet a third name: George Curley III.

The secretary at St. Michael's mission explained that, in those days, it was common practice to baptize the baby in the father's name followed by the birth order (in fact, George Curley I and II had actually been girls).

With the Catholic belief that if an unbaptised baby died, it would go to Limbo, it was more urgent to save a little soul than to record its correct name.

To complicate matters, Camron's mother's maiden name had been listed as "unknown," even though the entire family knew it was Clark.

As far as proving where and to whom Camron had been born, the document seemed worthless, but the secretary told them not to worry.

"The state," she said, "has seen this before."

The couple searched for records of Camron's mother's residency, and came across a tribal census document known as a "family card" that listed each enrolled member's dependants. But that was issued in the name of Camron's mother's first husband, who died six years before Camron was born.

As gas prices rose toward $4 a gallon, Camron and Fay made four trips to Phoenix to deliver the original documents ("After all that work, we couldn't risk having them lost in the mail," Fay explained). Each trip from Corrales to Phoenix required a motel stay.

Even getting the documents was expensive. The Social Security Administration, for example, wanted $27 to track down Camron's original application for a Social Security card.

"When you look at all these things, none of them really prove you were born at a certain time and place," Fay mused, rifling through the yellowed papers. "I think they just want you to jump through all the hoops to prove you're serious."

Crossing their fingers and holding their breaths, the couple dropped off the last of the documents.

Two weeks ago, the certificate of birth came in the mail. Camron applied for his CDL, and also a passport, which arrived last week. Just because, finally, he could.

"I don't really want to go anywhere, except maybe Canada to visit my son," Camron said. "But I feel like I should pave the way for the next person."

Just maybe, he already has.