Proud moment in a sad legacy: Fortress Rock

By Cindy Yurth

Tséyi' Bureau

This canyon, elegant, sexy, ancient, and all at once dangerous, demands the price of memory and the stories of jiní.

- Laura Tohe, "Tséyi': Deep in the Rock"

CANYON DEL MUERTO, Ariz., June 4, 2009

(Special to the Times - Donovan Quintero)

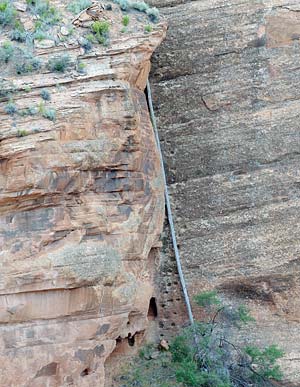

An aged log stands against the wall of Fortress Rock in Canyon del Muerto in Canyon de Chelley National Park. Foot and hand holes were carved into the rock next to the pole.

There are not many triumphant stories associated with the Long Walk, but the Navajos in these parts have one.

The story stretches one's credulity. There are few if any traces of it in the journals of the U.S. cavalrymen who would have witnessed it, but the elders here tell it with gusto and surprising consistency, and the evidence is there for anyone to see.

It is the story of how, using only ingenuity, teamwork and local materials, a handful of Diné were able to escape the Long Walk for nearly a month.

The story ends sadly - eventually all of the resisters were captured and joined the forced march to Hwééldi - but the fact that these Diné civilians were able to embarrass a well-armed mounted fighting force, however briefly, is a still a source of pride for their descendants.

It was the winter of 1863-64, cold but not yet snowy. The residents of Canyon del Muerto had already been approached by the U.S. government about voluntarily leaving their land and refused. Based on previous dealings with the white man, they figured the soldiers would not be far behind the smiling negotiators.

The Diné of Canyon del Muerto held a meeting and crafted a plan. They had successfully hid out from the Spanish on top of the slick-walled, 700-foot-high mesa they called Tsélaa. Maybe it would shelter them from the Americans as well.

The strong men were assigned to hike up the canyon walls to where the tall ponderosa grew and cut down the tallest ones they could find, then drag them back into the canyon to the base of Tsélaa.

The women, meanwhile, got busy drying fruit and meat to be cached at the top of the mesa for a long sojourn.

When all was ready, the Diné - some put the number at 60, some closer to 200 men, women and children - started the ascent.

There are handholds in Tsélaa carved by the Anasazi, but with packs full of food and water, elders in tow and crying babies strapped to cradleboards on their mothers' backs, it was a grueling hike. Even today, it's a climb few people have made.

When they came to cliff faces too steep to climb, the Navajos propped the big ponderosa poles against them, notched footholds into them and teetered up. They dragged the poles up behind them so their enemies couldn't use them.

Then they waited, using the time to pile rocks as bulwarks against bullets around the rim of the rock.

It wasn't long before the cavalry arrived. Possibly the soldiers saw fires on top of the rock; at any rate, they got wind of the plan. This will be easy, they must have thought. They camped at the cottonwood-rimmed spring at the base of the rock to wait the Navajos out.

According to Chinle resident Teddy Draper's account, quoted by Lawrence W. Cheek in "The Navajo Long Walk," the soldiers figured the Navajos would soon run out of food, and started frying bacon, hoping the smell would entice the Indians down the mesa.

But the Navajos had plenty of food. They did, however, run out of water some time during the second week of the standoff.

The leaders of the group had already anticipated this and devised an ingenious plan. They waited for a full moon night, then made a human chain down the mountain, each person locking wrists with the one above him.

While the soldiers slept, one of the stealthiest Navajo hunters crept to the spring, filling pot after pot passed down to him from above and sending it back up the human chain to the top.

Ironically, it was the cavalry that was running short of food. They hadn't anticipated this assignment taking this long.

After about three weeks, they packed up and left, and the Navajos climbed down, rejoicing that they had resisted capture and could stay in their beloved canyon.

Unfortunately, they had underestimated the government's designs on their land. It wasn't long before the soldiers came back, and this time, there was no time to hide.

This stunning tale is found in precious few history books, possibly because it relies mostly on "jiní."

The National Park Service plaque at Canyon de Chelly's Antelope House overlook, from which you can view Fortress Rock, does not even mention it, merely stating that "use of this refuge continued into the 1860s."

While the tale is widely recounted in "Del Merto," as the locals pronounce the canyon's name, most young people in nearby Chinle would have a tough time finding Fortress Rock on a map. Of a group of six local youths sitting on a curb in Chinle, only Derwin Claw, 19, had heard the story of Fortress Rock.

"It was a long time ago," he said. "I think I heard it in school."

But lest you doubt the story's veracity, Tsélaa itself holds the proof.

If you know where to look, you can still see the treacherous ponderosa poles leaning against the cliffs, and the bulwarks of stone on top.

To picture a young Navajo mom with a baby on her back shinnying up the poles stretches the imagination. But it happened. Jiní.