'The same funny laugh'

Mom and son reunite through Navajo Times letter

By Cindy Yurth

Tséyi' Bureau

CHINLE, Feb. 26, 2009

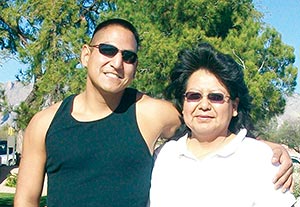

(Courtesy photo)

Cameron Page Curley, left, meets his birth mother, Sharon Sloan, Feb. 18 for the first time in Tucson.

There was no question in Sharon Sloan's mind that it was the right thing to do.

For the 19-year-old unwed mother, taking care of a premature baby would have meant dropping out of high school just when she was about to graduate, and what kind of future would that leave for the child?

The baby's father wanted nothing to do with them, and the last thing her own parents needed was another mouth to feed.

Yes, calling the adoption agency and giving her tiny, sickly infant a chance at a better life had undoubtedly been the right thing to do.

So why was it so hard?

And why, so many years later, after marrying and having five other children, did she still think about him so often?

After all, having weighed only 2 pounds at birth, maybe he was dead. At the very least, he was probably halfway across the country - she had asked for Native adoptive parents, and she didn't know many Natives in Arizona who needed another kid.

Still, "Every so often," said Sloan's best friend and clan cousin Molita Yazzie, "Sharon would say, 'I wonder what Eric is doing now? I wonder what he looks like?'"

A few hours away

In reality, baby Eric - whose name had been changed to Cameron Page Curley after the town where he was born and the town where his adoptive parents were married - was growing up in Prescott, Ariz., just a few hours from Sloan's home in Tempe. He had a white mom and a Navajo dad.

As Sloan had hoped, Curley was having a good life, after surviving an early struggle with the rare autoimmune disorder Kawasaki disease.

He had a loving family and enjoyed playing sports in school.

"But you wonder," he said. "I always wondered where I came from, you know?"

When he was 12, Curley wrote to his birth mom at the Tuba City address she had left with the adoption agency. He never heard back, and assumed she didn't want contact.

The truth was Sloan had already moved to Tempe, and whoever had her old post office box didn't bother to forward the letter. She never received it.

The years went by, and just hours apart, a mother and son went on with their lives and tried to forget about each other. It didn't work.

When Curley hit his early 20s, said his adoptive mom, Rita Volpe, "He started asking me a bunch of questions I couldn't answer."

Volpe had seen letters to the editor in the Navajo Times where people were trying to find long-lost relatives. She wrote one, trying to disclose enough details so that someone would recognize the scenario, but not enough to embarrass the birth mother.

The very next day, she got a call.

Sloan had learned about the letter from her parents in Tuba City.

"I was in shock," she said. "I thought Eric was probably gone."

She had to screw up her courage to pick up the phone and dial Volpe.

"I was afraid," she said. "I didn't know what she would think of me."

Volpe said she had never borne Sloan any ill will for giving up her child, and was ecstatic when Sloan contacted her.

"I never worried about having to share Page or anything like that," she said. "I just wanted him to have some answers. Everyone has the right to know where they came from."

A good kid

Sloan asked what her boy was like. Volpe replied he was a good kid: well mannered, easygoing, athletic, with a ready smile.

Volpe gave Sloan Curley's number. He was living in Tucson, just two hours from Sloan. The mother and son talked on Friday, Saturday and Sunday.

"We talked about family," Curley recalled. "She told me about my grandparents, my brothers and sisters, where I come from."

Curley learned his half-brothers, as he had, ran cross-country for their school teams.

He finally learned his maternal clan: Tó'aheedlíinii (Water Flowing Together, appropriately enough).

"I still can't pronounce it," he admitted. "I'm working on it."

By Sunday, Sloan and Curley were ready to meet. They arranged for Sloan to drive down from Tempe on Feb. 18, her day off from her job at a casino gift shop.

Sloan didn't sleep all Tuesday night. She enlisted some moral support from Yazzie, and the two set out for Tucson in the morning.

The closer they got to Tucson, the more agitated Sloan became.

"She kept saying, 'Open the windows! It's hot in here!'" Yazzie recalled. "I said, 'Sharon, stop it. The weather is fine.'"

In Tucson, they ran into that interminable road construction along the freeway. There was only one exit open.

"Then we both started to get nervous, because we didn't know where we were going and we knew we would be late," Yazzie said.

They managed to find Curley's house. A smiling young man was standing outside, flicking his gaze anxiously through the car windshield from Sloan to Yazzie and back.

My gosh, thought Yazzie, it's Eric all right. He has Sharon's smile.

"I said, 'Sharon, he doesn't know which one of us is his mom!'" Yazzie recalled. "'Get out of the car!'"

A long hug

"I was so nervous, I couldn't get the door handle open," Sloan said.

Once out of the car, the anxiety was gone. The mother and son who hadn't seen each other for 23 years shared a long, long hug.

"We hugged for probably like half an hour," Curley said.

Then he laughed.

"I thought, 'Wow, he has Sharon's same kind of funny laugh,'" Yazzie said. "Except louder."

Sloan told Curley he looked like his dad, but all Curley could see was how much he looked like her.

"I'm looking at this person I've never seen before, and I'm seeing my same facial features," he said.

He had never met a blood relative.

Sloan shared some family photos. Curley caught her up on his life and his current ambition to enlist in the military.

The two started planning a trip to Tuba City to meet Curley's grandparents and other relatives.

"I'm just really happy to have him back in my life," Sloan said.

"It went all good," added Curley. "I was kind of worried that it might be tense, but once we started talking it was like we'd known each other all our lives."

And he finally knows where he gets that silly, infectious giggle.