Hwéeldi at 150

Making peace with a painful past

By Cindy Yurth

Tséyi' Bureau

FORT SUMNER, N.M., Oct. 2, 2014

They are prime specimens of the present generation of Navajos: healthy, smartly dressed, and hopefully on their way to a good education and fulfilling lives.

Megan has never heard of the Long Walk. Summer says she knows "a little." Virgil, a descendant of Chief Manuelito whose favorite class is Navajo culture, provides a sort of Twitter version: "They marched us to Fort Sumner. We were really sad. We cried. Then we got to come home and we were all happy when we saw our land again."

Is it possible for the cellphone generation to truly appreciate the privations of their ancestors? Should they have to? How much should they be taught, and is it time -- 150 years after the Long Walk -- to break the old taboos against talking about it?

The fact is, the taboos have been broken for a long time, or we wouldn't know as much as we do. Almost every Diné family has a Long Walk story that has been handed down, either about going to Hwéeldi or escaping the cavalry somehow.

Evangeline Parsons Yazzie, former Navajo culture professor and author of the recent historical romance "Her Land, Her Love," asked nearly 5,000 Navajo elders for information that had been passed down to them and almost every one of them agreed to talk.

Virgil's mother, Priscilla "Percy" Manuelito, says her interest in the subject was lukewarm until, as a young child, two elders visited her school to talk to the children about it. One of them, who must have been over 100, was an actual survivor, having been born at Hwéeldi and made the trek back to Dinétah with her family as a toddler.

"I think it was the details she gave -- how even on the way back, they were looking around, making sure no one was going to catch them again; how the children were not allowed to cry; how everybody fell to their knees at the first sight of Mount Taylor -- that really made it sink in, how much they had suffered," Manuelito mused. "I'm so glad I got to have that experience; that the lady was willing to share her story with us."

Tragic trail

A stronger taboo surrounds the actual trail and destination of the Long Walk, known variously as Bosque Redondo ("Round Forest), Hwéeldi (possibly a corruption of the Spanish word "fuerte," "fort") or Fort Sumner (after Civil War hero Col. Edwin Vose Sumner, who actually opposed the reservation).

There are those even now -- including some in the tribe's Historic Preservation Department -- who don't believe people should tread in those tragic footprints.

Just a few years back, the National Park Service studied the route as a potential national historic trail.

"We did a thorough study and discovered it met all the criteria for a national historic trail under the National Trail System Act," revealed Aaron Mahr, superintendent of the Park Service's National Trails Office in Santa Fe. "We held public hearings at a lot of the chapters, and it had a lot of support. There were also some elders who were very uncomfortable with the idea."

Ultimately, the Navajo Nation Council voted the national trail proposal down, and the Park Service abandoned the project. The NPS turned over the study to the tribe, and it is presently archived at Historic Preservation, where Tony Joe, supervisory anthropologist for the Traditional Culture Program, guards it with his life.

Joe refused to share the study with the Times for this article or even disclose some details of it over the phone.

"When they came back from Fort Sumner, our leaders at the time told us never to go back to that place," Joe stated, "and it is the tribe's position to take that advice."

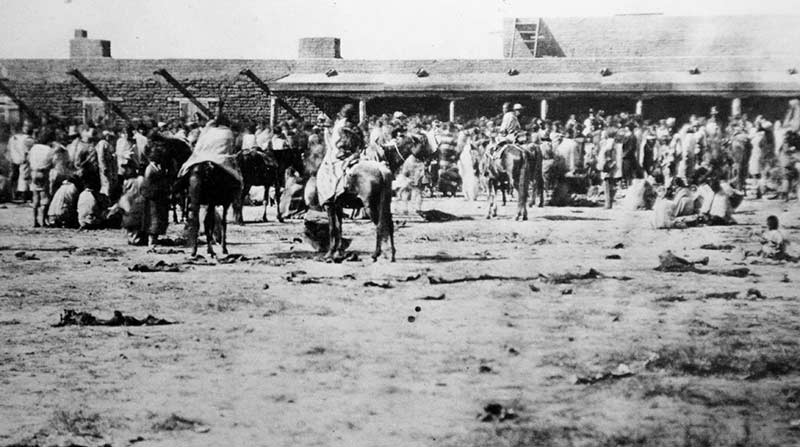

There's no doubt that the Bosque Redondo in eastern New Mexico -- the million-acre reservation where 8,000 Navajos and 500 Mescalero Apaches were forced to eke out a living between 1864 and 1868 -- conjures up nothing but bad memories for the Diné.

Two thousand Diné internees -- one out of four -- died there, of dysentery, exposure or starvation, and are buried in unmarked graves on the northern quadrant of the present 250-acre historic site, not far from where Billy the Kid met his fate.

Diné visitors

But over the years Fort Sumner -- now the state-funded Bosque Redondo Memorial -- has been visited by at least two Navajo Nation presidents (Peterson Zah and Joe Shirley Jr.), Navajo medicine men, Navajo historians, Navajo schoolteachers and their classes, not to mention hundreds of Navajos who just want to see it for themselves.

"Probably the majority of our visitors are Navajo," said Mary Ann Cortese, president of the Friends of the Bosque Redondo Memorial, a volunteer group that fundraises for the site and works with Navajo and Mescalero Apache tribal members to design the exhibits.

"Many of them come to pray. Some of them come to leave something behind."

At the "Navajo shrine," a spot near where the Treaty of 1868 was signed, Navajos over the years have left stones from Dinétah or wherever they now call home, jewelry, coins and currency, war memorabilia and, in one case, a Purple Heart medal.

It was a note left by seven young Navajos at the shrine in 1995 that inspired the present memorial, which includes a spacious visitors' center, a self-guided walking tour of the grounds, a reconstruction of the fort's foundation (all the original buildings have been swept away by the flood-prone Pecos over the last century) and one of the soldiers' barracks.

"At the time," said Cortese, "the only thing here was a small visitors' center that basically told the story from the soldiers' point of view."

The note said, "Why don't you tell our story?"

A change of view

That inspired the state to rethink the site as a memorial to the Native Americans who were interned there, both those who survived to return home and those who died.

A committee comprised of representatives of both tribes along with state personnel came up with the present design, including a visitors' center incorporating both Apache and Navajo symbolism that takes visitors up a gently sloping ramp flanked by two murals.

On the left, Navajo artist Shonto Begay has portrayed a long line of ragged, trudging Native men, women and children; on the right, an Army regiment depicted by local artist G. Donald Bain points guns or just scowls at the Natives -- and the visitors trapped between the two sides.

"Creepy!" exclaimed Melinda Gonzales of Roswell, N.M., who was at the monument with her husband Isidro Sunday in hopes of finding some information on an ancestor who was interned there.

Roybal gently explained that no records of the internees were kept by name; only tallies. In September of 1864, for example, we know that 7,384 Navajos and 430 Apaches were here. (The Apache count eventually dwindled to zero; every one of them managed to escape.) The Army did record, however, the name of every soldier stationed here, and occasionally their descendants show up, too.

The ramp leads up to a central theater where visitors can watch an informative film.

But for those who have lived on the Navajo Reservation, the most striking part of the monument is the landscape outside.

"You can see," said Cortese, "it looks nothing like the Navajos' homeland."

Flat grasslands stretch out in every direction -- no sacred mountains, no canyons, no trees except the ones planted by park staff and the ancient cottonwoods the military forced the Navajos to plant along the road from the town of Sunnyside (now named Fort Sumner, after the fort the Natives built for their captors). Today, the grounds are planted in native grasses and pretty little farms surround the site, and it takes a some imagination to picture it as the Navajos must have first seen it: a dusty wasteland they were supposed to farm with the alkaline water of the Pecos.

Sad but stunning

On the day the Times visited, the weather was perfect, but a ridge in distance sports a long line of power-generating windmills, which are there for a reason. The locals will tell you it's a rare day when the wind isn't blowing here.

It's a sad place, but also a testament to the human spirit.

"What I hope people take away," said Roybal, "is how much these people wanted to survive, in spite of how awful their life was here. They never gave up the thought that they would one day go home."

The Times crew had planned to approximate the route of Long Walk on the way to Fort Sumner, but the gods did not seem to like that idea (the reporter's car broke down en route). We compromised by retracing the trail in the happier direction: the way home.

It's really no secret; coming from Fort Sumner, if you take I-40 west to I-84, shoot up 84 to I-25 to pass through Santa Fe and Albuquerque, and then take I-40 home through Gallup, you've pretty much approximated the route your ancestors walked (although it will it will take you a day vs. a month).

Even traveling by interstate freeway in a modern car, it's a long, desolate journey. But it doesn't give you the feel of the elements, the hunger, the uncertainty of whether you would survive or be left to the coyotes along the way.

We asked Yazzie if there was a quick way for modern folks to connect to the Navajos who made the grueling trek.

"Take off your shoes," she advised, "and walk across the lava fields near Grants."

Cousins Virgil Manuelito, Summer James and Megan James meet us at the Grants McDonald's to see if they can follow in the footsteps of their great-great-great-grandparents.

We find a nice rough patch of lava rock and take off our shoes.

"Socks too?" asks Virgil.

Yes, the Diné of old did not have socks.

"Look how white my feet are!" Virgil laughs, showing a clear tan line just above his ankle.

The joy soon turns to agony.

"Ow ow ow!" howls Virgil. "How did they do this?"

The girls silently pick their way in single file, tiptoeing over the black shards. After a few yards, we're all spent.

"That was horrible!" exclaims Virgil. "I have a lot of respect for the people that did this."

If the children's ancestors are watching, one can only imagine that they're smiling, proud that they endured unfathomable hardship, and survived to produce offspring whose tender feet would not have to know a life outside of their canvas and rubber moccasins.