Navajo woman tried for years to share Ruess story

By Cindy Yurth

Tséyi' Bureau

CHINLE, April 30, 2009

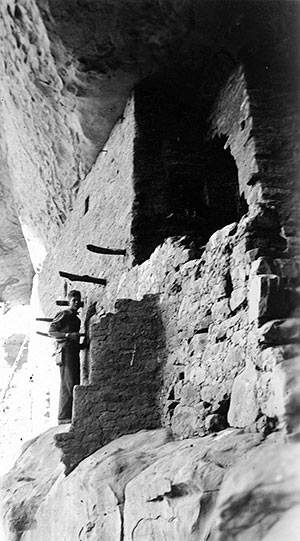

(Courtesy photo - EverettRuess.net, used under license)

Everett Ruess is shown at Mesa Verde in Colorado in this undated photo.

For 75 years, people have been looking for Everett Ruess. For 38 years, Daisy Johnson of Shiprock has been telling a story passed down from her grandfather about a young red-haired white man killed by Utes in the mid-1930s.

Somehow, the searchers and the Navajo woman never found each other, and Ruess’s brother Waldo died without knowing what happened to the young poet, artist and desert wanderer who disappeared near Escalante, Utah, in 1934.

Now the mystery is solved — sort of.

Through DNA matching, "we were able to show unequivocally" that a skeleton found by Johnson’s brother on Comb Ridge was "a very close blood relative" of Ruess’s surviving nieces and nephews, University of Colorado molecular biologist Kenneth Krauter told reporters during a telephone press conference hosted by National Geographic Adventure magazine Thursday morning.

The magazine had sponsored the investigation, and a report on it appears in its most recent issue.

The DNA evidence, combined with Johnson’s story and matching skull fragments to photos of the 20-year-old Ruess, makes "an irrefutable case" that Ruess’s body has at last been found, Krauter said.

How Ruess managed to cross the Colorado and San Juan Rivers and travel 60 miles from his last known camp in Davis Gulch, Utah, when he was planning to go the other direction — well, that’s still a mystery for future sleuths. The fact that Ruess’s body turned up in a place no one had ever looked for it may explain why no one ever asked the Navajos around Buff, Utah, if they had encountered a wandering young white man.

Had they asked, Johnson told reporters ranging from the New York Times to the Navajo Times, Ruess’s whereabouts may have been established decades ago.

"There are stories all over Bluff and Red Mesa about a young Anglo man who used to come to the houses and live with the people for a week or so," Johnson said. "There are even ceremonies involving him."

Johnson first heard the murder story in 1971, when her grandfather, Aneth Nez, was being treated for cancer.

"They took him to a medicine man and the medicine man told him what he had done," Johnson recalled.

Nez had moved a dead body and been splashed by blood, and that was why he was sick, the singer said.

Johnson said she overheard her grandparents arguing about the incident and her interest was piqued.

"My grandmother said, ‘You should never have messed with that body!’" she recalled. "My grandfather said, "He was a human being; he deserved a decent burial. I put him away before the coyotes could get to him."

Johnson, a young woman at the time, was shocked.

"What body?" she demanded. "What are you talking about?"

That’s when she first heard the story: Nez had been sitting atop Comb Ridge some time in the 30s when he observed a young Anglo man riding one burro and leading another in the bottom of the Chinle Wash. Three Ute men were chasing him, and he was riding fast. They caught up and one of the Utes bashed his head in with a rock, took his burros and rode away.

Nez waited until the murderers were gone, stole into the wash, dragged the body up a slope, stashed it in a crevice and covered it with rocks.

Johnson said she never made a secret of the story.

"All these years, I’ve been telling people, ‘There’s a man out there that needs to go home,’" she recalled.

A few times, she called the TV show "Unsolved Mysteries," "but I just got a recording saying, ‘All circuits are busy,’" she said.

Eventually, she told the story to the right person: her younger brother Dennison Bellson.

"Denny was the only one who ever followed up on it," she said.

Ironically, neither Johnson nor Bellson had ever heard of Everett Ruess. After he heard the story last spring, Bellson got on the Internet and searched a database of missing persons reported in southern Utah. Ruess was the only one who matched Nez’s description: a young, red-haired white man traveling alone with two burros.

After Nez was diagnosed by the medicine man, Johnson drove him to Comb Ridge to look for the body. The medicine man had told him he would need a lock of the dead man’s hair for a ceremony to cure Nez’s cancer.

Johnson dropped her grandfather off at a certain point, and waited for him — she never saw the grave. But last May 25, she was able to show Bellson on a map the direction Nez had walked.

From the road, Bellson said, he walked about two hours before he saw a piece of leather that turned out to be, probably, his grandfather’s saddle, abandoned because it too had been contaminated by blood. Nearby he saw a crevice covered with rocks, and peeked between them to see a skeleton.

Bellson originally called the FBI, but after a cursory investigation they declared the site a Native burial and closed the case.

According to National Geographic Adventure contributing editor David Roberts, who wrote the story on the find, FBI agents actually compromised the site by throwing the saddle into the crevice on top of the body, crushing the skull.

Juan Vecerra, spokesman for the FBI’s Salt Lake City office, did not return a phone call to respond to that allegation.

Bellson didn’t believe the grave was Native. All the details matched his grandfather’s story too closely.

"When I looked at him, I just knew," he said.

A friend suggested he contact Roberts, who had written an article 10 years previously about a failed search for Ruess. Roberts contacted the CU anthropologists who eventually cracked the case.

Meanwhile, Johnson was doing a little sleuthing of her own. Bellson had shown her pictures of Ruess on the Internet.

"When I saw that picture, for some strange reason, it did something to me," she said.

She asked her mother if she had ever encountered the strange young wanderer in her younger years. She had.

"My mother said, ‘At a very young age, this person had respect for Mother Earth, the sun and the moon,’" Johnson recalled. "’In your life, some of you will never acquire the respect that he had.’"

That description seemed to match the man she and Bellson had read about, who combed the red canyons, as he said, "in search of beauty."

Ruess’s niece Michelle Ruess, also on the conference call, said she appreciated hearing these details of her uncle’s last days.

Ruess was "very much a part of our family" even after his death, she said, and as recently as 1981 her father had written a letter to the editor of Desert Magazine imploring readers to reveal any traces of Ruess they had encountered while hiking in the desert. Waldo Ruess died at the age of 98 – just nine months before Bellson found his brother’s remains.

"I’ve heard people say, ‘Wouldn’t it have been better if it had just remained a mystery?’" Michelle Ruess said. "That’s not how the family feels. We’re very appreciative and very grateful to have the mystery solved.

"We’re happy there was such a person as Aneth Nez who gave him the opportunity of a respectful burial."

For now, Ruess’s bones remain "securely stored" at the University of Colorado, according to CU anthropology professor Dennis Van Gerven, who used the skull fragments to reconstruct Ruess’s features for the identification process.

"We await instructions" from the family, Van Gerven said.

Ruess said the family would like the remains delivered to California where they will be cremated and scattered over the Santa Barbara Channel — "our family burial plot."

She closed the press conference with her uncle’s words:

"So until then, live gaily, live deeply and wrest from life some of its infinite possibilities."