Asbestos fine reduced?

Workers faced dangerous asbestos exposure at Aneth Gas Plant, NOSHA says

By Marley Shebala

Navajo Times

MONTEZUMA CREEK, Utah, May 21, 2009

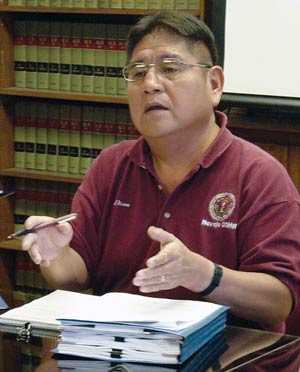

(Times photo - Marley Shebala)

Navajo Occupation Safety and Health Administration inspector Edison Owens reported to the Utah Navajo Commission on Wednesday about asbestos removal violations at the former Aneth Gas Plant near Montezuma Creek.

Nearly two dozen workers were exposed to cancer-causing asbestos while working for an asbestos removal company under contract to Chevron, Navajo Nation Occupational Safety and Health Administration inspector Edison Owens told the Utah Navajo Commission on May 13.

Moreover, he said, the entire community of Montezuma Creek, Utah, may be at risk of exposure due to unsafe practices by Envirocon Inc., which was hired by Chevron to remove asbestos from its now closed Aneth Gas Plant.

Owens' charges come less than two months after NOSHA shut down work at the site, citing an imminent threat to workers, and reportedly levied fines of more than $15 million against Chevron and its contractor.

His warning prompted the commission to call for special meetings on the situation.

Speaking at a commission meeting in Window Rock, Owens reported that he made the discovery during an Aug. 21 field inspection of the gas plant, which is located on a bluff overlooking Montezuma Creek.

NOSHA's field inspection resulted in a stop-work order - the most stringent enforcement action the agency can take and one that is only imposed when workers face a serious threat to their health or safety.

Chevron, which owns and operated the plant, hired Envirocon to demolish the plant as part of a plan to turn over the property to the Navajo Nation.

Envirocon, which is based in Missoula, Mont., had hired Maryboy LLC of Montezuma Creek, Utah, as a subcontractor to perform the asbestos removal.

NOSHA learned of the asbestos problems at the plant from Maryboy officials. The Maryboy workers arrived at the site to find that considerable demolition has already been done, leaving asbestos exposed where it would become airborne and could be inhaled by workers or could be blown by the wind onto the nearby community.

Asbestos is a proven cause of mesothelioma, a type of lung cancer.

Exposure is forever

Owens emphasized to the Utah Navajo Commission that he is very concerned about the 23 people who had been working at the site, saying, "They will die."

They may not die today or tomorrow because the cancer that is caused by asbestos only surfaces in about 20 or 30 years, he said. And once an individual is told that he or she has been contaminated with asbestos, it will change that person's lifestyle and mental attitude, he added.

Owens recalled that during the Aug. 21, 2008, inspection, he saw asbestos loose on the ground. Asbestos is dangerous when loose, or "friable."

He said he personally called U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to report it. Owens said he spoke with Bob Trotter, an official in the National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants office in San Francisco, which includes oversight for asbestos abatement rules. Owens urged Trotter to come down and see the Aneth Gas Plant.

He said Trotter responded by asking him to send pictures. Trotter, whose agency is mandated to guard public health, later told the Navajo Times that NOSHA, which is limited to enforcing workplace safety standards, was doing a "great job" of handling the problem.

"This is an environmental issue," Owens stressed to the contrary. "We need your help. Get these people to help us."

He said NOSHA needs to do more monitoring of the asbestos abatement at the gas plant site, and noted that its authority ends at the workplace boundary.

NOSHA director Timothy Bitsie, also addressing the commission May 13, recalled that when NOSHA inspectors were at the plant last August, he saw about 25 school-age children in the vicinity of the site.

Owens and Bitsie reported that their field inspection resulted in Envirocon and Chevron being charged with 65 violations of federal workplace safety laws.

However, Bitsie declined to comment on the original size of the fine or on reports that it had been lowered from millions to thousands of dollars following negotiations between NOSHA and Envirocon.

On Dec. 3, he lifted the closure order that had been issued.

"The source of the unsafe asbestos abatement work practices has been since corrected," he stated in the authorization to Envirocon to resume operations.

On March 31, Council Delegate Kenneth Maryboy (Mexican Water/Aneth/Red Mesa) issued a press release stating that Envirocon was fined more than $15 million "for the violations and for exposing Navajo workers, surrounding communities and others to the carcinogenic fibers.

"Chevron and Envirocon are denying any responsibility," he stated in the release.

Maryboy accused Chevron and Envirocon of trying to eliminate Maryboy LLC as the subcontractor on the project after it blew the whistle to NOSHA. Maryboy LLC, which is owned by a Navajo female (no relation to Mark or Kenneth Maryboy), put its workers through special training to qualify for the job.

Mark Maryboy, a former council delegate who attended the commission meeting as a concerned citizen, told the commission that the fines had been reduced to thousands of dollars.

Information off limits

Council Delegate Davis Filfred (Aneth/Mexican Water/Red Mesa), a member of the Navajo Utah Commission, asked for more information about the 65 violations, but was cut short by fellow commissioner and delegate Katherine Benally (Dennehotso).

Benally urged Paul Spruhan, assistant attorney general for the Navajo Nation, to go into executive session, during which the public is excluded from the meeting.

Spruhan did so, explaining to the commission that a settlement conference was held between NOSHA and Envirocon in March.

He said the settlement terms are confidential, calling it "standard practice," and said the commission could hear the rest of NOSHA's report behind closed doors.

Under federal law, enforcement actions under the Occupational Safety & Health Act, including negotiated settlements, are public record. The only exception in the law is that a company's trade secrets are subject to protection.

Spruhan represented the tribe during the negotiations with Envirocon's attorneys, which included former Navajo president Albert Hale.

In response to questions by the Navajo Times about his authority and expertise to negotiate away multi-million fines, Spruhan said, "None of it is relevant. I'm not commenting."

After Spruhan's presentation, Filfred and Kenneth Maryboy both said that information regarding the public's safety was once again being withheld in the interest of non-Navajo corporations.

"They're walking all over us," Filfred said. "They probably only got a slap on the wrist. What is it going to take for those guys to negotiate with us?"

Filfred was referring to Charles Bird, director of the Envirocon-Aneth Gas Plant, and Eric Page an environmental management company/remediation project coordinator for Chevron, who were sitting in the commission meeting to report on the plant project.

Kenneth Maryboy said he was very concerned about the children living downwind of the plant, noting that both Owens and Bitsie had emphasized that asbestos "will kill you."

Kenneth Maryboy, who also sits on the council's Economic Development Committee, said he had scheduled a committee Wednesday, May 20, in Kayenta to discuss the Aneth gas plant situation.

"Today I'm concerned what Mr. Maryboy is saying," Owens said on May 13. "He wants to hear all the facts and I can share it."

Navajo Utah Commission chair Francis Redhouse (Teec Nos Pos) said that instead of going into an executive session, the commission would set a couple of special meetings to hear from NOSHA.

Page, in a brief interview May 13, emphasized that Chevron and Envirocon are very concerned about public health, and have hired an asbestos inspector to oversee the project with NOSHA. The work plan was reviewed and approved by NOSHA and the Navajo EPA, they also said.

When asked why it took a closure order and heavy fines before Chevron and Envirocon acted to protect the public's health, Page said, "I would say that I'm not sure how to answer that question."