'A beautiful gold medal'

Long-lost U.S. military medal unlocks memories of code talker, tribal judge

By Marley Shebala

Navajo Times

WINDOW ROCK, Sept. 4, 2010

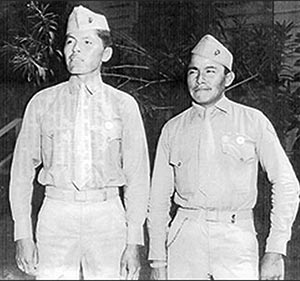

TOP PHOTO: Defense Dept. Photo (Marine Corps) #145995: On March 2, 1947, Marine privates first class Alec E. Nez of Flagstaff and William D. Yazzie of Teec Nos Pos competed in the Marine Corps Pacific Division Rifle and Pistol matches at Puuloa Point, near Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Yazzie won a gold medal for third place and Nez won a silver medal for fourth place. (Courtesy photo)

BOTTOM PHOTO: U.S. Marine veteran Fuzzy Melton and his wife Gail returned a long-lost 1947 sharpshooters medal to Mary Louise Defender-Wilson, widow of the late Navajo Code Talker William Dean Wilson. (Times photo - Paul Natonabah)

The exact date that the late Navajo Code Talker William Dean Wilson of Teec Nos Pos, Ariz., lost his medal, given for excelling in a 1947 Marine Corps Pacific Division Rifle and Pistol Competition, is unknown.

But it found its way home to his wife, Mary Louise Defender-Wilson, who lives on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota, in early August 2009.

In a Tuesday telephone interview, Defender-Wilson said Wilson returned from one of his many code talker trips in the early 1980s and said that he had lost some things.

Wilson, who was Áshiihí (Salt Clan), born for Tódík'ózhi (Salt Water Clan), traveled often to make public appearances with other code talkers after the U.S. publicly recognized their existence in 1969, she said. (Before that, their existence was a closely guarded military secret and they were all sworn to secrecy.)

Defender-Wilson put down the phone momentarily and retrieved Wilson's long-lost medal, describing it over the phone.

"It's a beautiful gold medal," she said. "There's an enameled center where two rifles are crossed. The center is a target."

According to the caption on a March 2, 1947, military photo, Brigadier Gen. H. D. Linscott presented the medal to the young Navajo - then known as William Diné Yazzie - after he took third place in the Pacific Division shooting match, held at Puuloa Point near Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

The annual competition pits elite marksmen from each service branch in a series of matches that eventually selects a national champion.

Standing beside Yazzie in the photo is Marine Pfc. Alec E. Nez of Flagstaff, who placed fourth and received a silver medal.

Lost on a plane

Yazzie's gold medal was found by an airline employee cleaning out a plane after a commercial flight, and was put in the lost-and-found of the airline company, according to Marine veteran Fuzzy Melton of Axton, Va.

The company gave it to the employee after no one claimed it, and he in turn gave it to Melton as a Marine memento two years ago when the two friends were attending the annual Memorial Day Rolling Thunder tribute in Washington, D.C.

Melton said he turned the medal over and saw that it was inscribed with the name "WD YAZZIE" and year "1947." He then began a yearlong search of military libraries that lead him to Zonnie Gorman, the daughter of the late Navajo Code Talker Carl Gorman, and the revelation that W.D. Yazzie was a code talker.

Gorman was a close friend of Yazzie, so his family knew that W.D. Yazzie had become William Dean Wilson after the war, was deceased, and had a widow living in South Dakota.

Defender-Wilson recalled her husband telling her that he used his grandfather's name, William Diné Yazzie, to enlist in the Marines at the age of 15 or 16. When he returned from the war he learned that some missionaries had named his father Paul Wilson, so he took that last name. His middle name morphed from Diné to Dean over the years.

Wilson met his future wife at Haskell Indian School in Lawrence, Kan., where he enrolled after the war.

Defender-Wilson laughed gently as she remembered that a lot of Navajo boys were sent to Haskell after they were discharged from the military.

She and William took their time getting to know each other and didn't marry until 1969.

She remembered with more laughter the irony of growing up herding sheep and eating mutton on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, and then marrying a Navajo, whose people's connection to sheep is legendary.

She said the one thing she remembers about her husband is that "he always talked the Navajo language and sang those Navajo songs. And he loved Navajo food."

Up to that point in the interview, Defender-Wilson had been very talkative but suddenly there was a long silence.

"I would like to say that it's very, very important to be involved with the culture of your people because that's what makes you strong and able to accomplish a lot in one's life," she said softly. "And try to pass it on to the future generation because all of that is who we are as people. And that's what he did."

A life of service

Defender-Wilson said her husband became a judge after the late Annie Wauneka recruited him in the early 1960s.

"The Navajos were upgrading their judicial system and were seeking responsible tribal members to apply, so he applied and was hired," Defender-Wilson said.

Throughout his career, Wilson presided in the Shiprock, Chinle and Window Rock district courts and served temporary assignments in Tuba City and Crownpoint, before retiring.

Defender-Wilson said that throughout his time on the Navajo Nation bench, he also served in the Marine Corps Reserves and retired after 20 years of service.

She added that Wilson also continued to represent the Marines in military shooting competitions across the country.

Once the code talkers were released from their vow of silence, they received many invitations to appear in public. Defender-Wilson remembers that her husband, one of the original 29 code talkers, always wore his gold sharpshooter medal when he donned his Navajo Code Talker Association uniform.

Fortunately for history, photographer Kenji Kawano photographed Wilson wearing his medal before it disappeared. The photo graces the cover of Kawano's book, "Warriors - Navajo Code Talkers."

On Wednesday, Kawano recalled that Wilson asked him to take his photo in front of the Iwo Jima memorial in Washington, D.C. The date was July 4, 1983, and Wilson and other code talkers had been invited to the nation's capital to march in an Independence Day parade.

Kawano's book was published in 1990, 11 years before President George W. Bush presented each of the original 29 Navajo Code Talkers with a Congressional gold medal in a ceremony in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol.

Wilson, who had died Dec. 19, 1999, received his medal posthumously.

On Tuesday, Defender-Wilson said she didn't know how prestigious his first gold medal, the Marine Corps marksmanship medal, was until she met Melton and his wife, Gail.

Last year the Meltons rode a motorcycle from their Virginia hometown to Porcupine Creek, N.D., a journey of about 1,700 miles, to personally deliver the lost medal to Wilson's widow.

Last month, the Navajo Times learned of the story when the Meltons came to Window Rock for Navajo Code Talker Day, where Melton had been invited to tell the story of the medal's return.

Melton said he and his wife did the months of research and drove those hundreds of miles because the medal's owner was a code talker.

"And it was the Christian and Marine thing to do," Melton said. "He was my Marine brother."