The controversial Sioux, Indian rights activist dies at 72

By Bill Donovan

Special to the Times

WINDOW ROCK, October 25, 2012

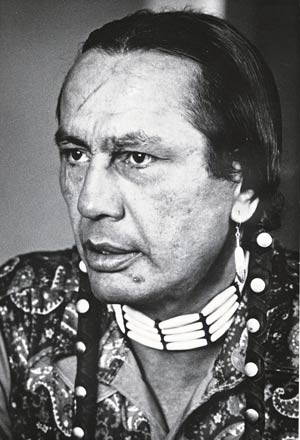

TOP: (Times file photo) Russell Means listens during a press conference in the 1980s.

SECOND FROM TOP: (Times file photo – Paul Natonabah) Russell Means puts a headlock on James Stevens, Bureau of Indian Affairs Navajo Area Director at the time, at Stevens' office in Window Rock, Ariz. in July 1989, as Means tried to make a citizen's arrest. Two BIA police officers move in to stop Means.

R ussell Means, the Oglala Sioux activist, speaker and film actor who died Monday at the age of 72, never turned his back on controversy.

That was true of all of the years he was a leader of the American Indian Movement and it was true of the few years he spent living in the Chinle area of the Navajo Reservation.

He died at his home in Porcupine, S.D. on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation of esophageal cancer, a disease that affected his tongue, lymph nodes and lungs. Media stories about his death said that when he was told in the summer of 2011 that he had the disease and that it was incurable, he opted to treat his illness with herbal and other native remedies instead of with the western medical treatments.

Means was probably most known to non-Natives from his works in movies such as "The Last of the Mohicans" or from his hundreds of protests throughout his life and his involvement with the occupation of Wounded Knee, S.D.

At the end of that 72-day occupation, Means was tried for assault, larceny and conspiracy, but the case was thrown out by a judge because of misconduct from the prosecution.

Here on the Navajo Reservation, he was most known for three things - his undying support of former Navajo Tribal Chairman Peter MacDonald during his period when he was suspended by the 49ers and went to federal prison, his decision to arrest a BIA area director for crimes against the Native people and for his almost decade-long dispute with the Navajo Nation over a paternity dispute.

He came to the Navajo Reservation after he married Gloria Grant, the first of two Navajos wives he would have.

While Means was living in Chinle, MacDonald was finding himself in deep trouble from 1988 to 1989 with members of Congress and the majority members of the Navajo Tribal Council over his involvement in the purchase of the Big Boquillas Ranch a 491,000-acre ranch west of Flagstaff.

That was the ranch the Navajo Tribe bought from Bud Brown and Tom Tracy, two non-Indians, for some $34 million just minutes after they bought it from someone else for $26 million.

This led to MacDonald's suspension and a series of demonstrations that ended with a riot in front of Administration Building No. 1 and resulted in the death of two MacDonald supporters from gunshot wounds.

Throughout this ordeal, according to statements made by Means at the time and from which he wrote in his 1995 autobiography, "Where White Men Fear To Tread," MacDonald would ask him for advice.

This really wasn't that strange since Means throughout the ordeal was saying that MacDonald's problem was being caused by outside interests, including BIA officials, who wanted him brought down so he would lose his power.

Means urged MacDonald to fight those on the Senate Select Sub-committee on Indian Affairs who wanted him to go to prison for his involvement in the deal.

Means urged MacDonald to demand a chance to speak before the committee so he could say that if the purchase of the ranch was a good deal for the non-Indians, it was a better deal for the Navajos. On saying that, Means urged him to just stand up and walk out of the meeting room, refusing to answer any questions.

But MacDonald balked, according to Means in his book, saying he was afraid he would be held in contempt of Congress. "You have contempt for Congress," Means, said, adding there was no chance that MacDonald would get a fair hearing.

MacDonald never did this and Means said he wished he had taken his advice because by doing nothing, he dealt with the feds from a weakened position.

After that confrontation in July 1989, Means sponsored another march in front of the administration building about a week later but by then MacDonald supporters were still reeling from the shock of the two deaths. Means was only able to get a few die-hard supporters - mostly women - to join in what would be the final march in the dispute.

But about the same time, means was able to get his name and his picture in the Navajo Times and other papers throughout this area because of his attempt to place Fred Stevens under civilian arrest for alleged crimes against the Indian people.

Stevens was in his office in the building in Window Rock directly across from the Navajo council chambers holding a press conference to explain what the BIA was doing about all of the turmoil that arose after MacDonald's suspension.

Means asked for permission to attend the event and Stevens said before the conference that he had no idea what Means would do but he wasn't going to take any chances. Stevens had three or four BIA police officers waiting in the next room if there was any trouble.

Means was standing to the side and halfway through the press conference, he said, "I can't take this anymore" and rushed up to Stevens and grabbed his arm and placing him behind his back as if he was going to put handcuffs on.

Photographers captured all this for the Navajo Times and other papers at the scene. He didn't have a hold of Stevens for more than a few seconds because the BIA police immediately placed him under arrest although he would later say that Stevens was trying to grab his braids and that he wouldn't let him go.

The decision was to prosecute him in tribal court instead of in federal court but nothing came of this because of another dispute that Means would fight with the Navajo government over for years – whether the tribal courts had any jurisdiction over him because he was not Navajo.

He and his attorneys said the Navajos didn't have authority, which created quite a stir because the Apache County Sheriff's Office said they didn't have jurisdiction since they only arrested whites on the reservation who violated the law. As for the federal government, they had jurisdiction but they didn't handle misdemeanors, leaving that to the tribal court.

At about the same time, Means was in an argument with the Navajo police and courts over problems he was having with his wife and his father-in-law, Leon Grant.

There were accusations that Means had a domestic violence incident with his wife and that he may or may not have hit his father-in-law during another confrontation. In any case, his wife told him that there had been complaint forms filed against him and that Navajo police would be coming to pick him up.

This is from his book: "I knew I was in trouble. The cops could fill in those forms and allege anything they wanted. After all of the confrontations I had had in the 1970s, I knew they would do so.

"Expecting the police, I decided I wasn't going to jail. I borrowed guns and ammunition and fortified my home office with mattresses and furniture piled up against the windows and walls…"

Means said he stayed awake all night expecting the Navajo police to show up but they never did. What he didn't realize is something that most Navajos have come to know - Navajo police are very slow to serve warrants and it can be weeks, months or even years before they get around to it.

He was also in another dispute over the paternity of a boy his wife had after they got married. Gloria Grant had been married before to a non-Indian by the name of Gary Davis and Davis claimed that he was the father of the boy and not Means. He wanted visitation rights.

Means' wife supported his version but the matter went to the Navajo family court where the judge ordered a paternity test to determine just who was the father. Means, however, refused to take the test or allow it to be taken on his son, saying that this violated Sioux tradition, even though Sioux leaders contacted by the press said this was a new tradition to them.

The matter went all the way up to the Navajo Nation Supreme Court, which also ordered that the paternity test be done but Means continued to refuse and by this time had taken his son back to the Pine Ridge Reservation where he was being kept hidden. Eventually, all parties got tired and the dispute died out.

What didn't die out, however, was the assault charges that had been filed against Means for the alleged assault of his father-in-law. Means fought this by continuing his augment that the Navajos didn't have jurisdiction.

The Supreme Court disagreed and Means then took it to the federal district court where it languished for several years until that also just went away and Means was never tried on the charges.

A few years later, Means came back to Gallup to talk about one of his movie roles and was asked about the so-called confrontation he was expecting with Navajo police and he admitted that the may have overreacted.

He was sill protesting - mostly the observance of Columbus Day - but he and the Navajo Nation seemed to have mended their differences.