‘Big victory for Indian Country’, US Supreme Court upholds protections for Native children

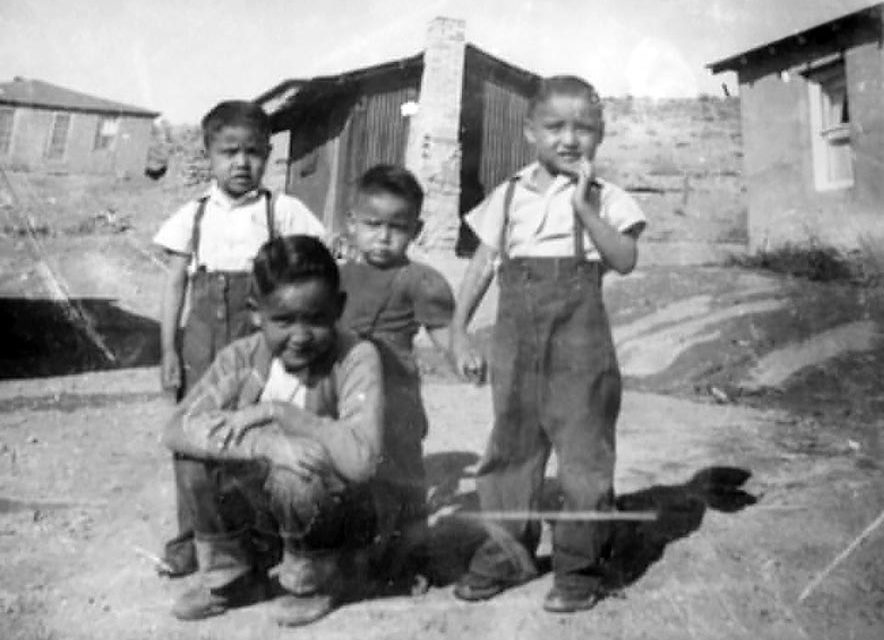

Courtesy photo

Ambrose Ashley’s family before the children were placed in different foster homes. Ambrose, center back, holds his brother Melvin’s hand as his brother Anthony stands to his left and his brother Eugene sits in front of them.

DADEESTŁIN HOTSAA

Former President Jonathan Nez was on a tour of the Capitol when the Supreme Court upheld the Indian Child Welfare Act.

“It’s a big, big victory for Indian Country,” Nez said in an interview with the Navajo Times Thursday morning.

Nez’s administration heavily supported protecting ICWA – the gold standard in child welfare policy – to end destructive child removals.

“It’s important that our Native American children stay with their tribal nation, their family,” Nez said. “Today, it was acknowledged.”

By a vote of 7 to 2, the justices rejected the challengers’ claim that the requirement was a form of unconstitutional racial bias against Natives.

“We were thinking it would be 5 to 4, but 7 to 2––(Justice) Amy Coney Barrett being the author of the decision, was even more surprising,” Nez said. “I briefly got an overview of the opinion, the statements. And it goes further into strengthening the sovereignty of tribal governments.

“The recognition of the Supreme Court, at least the seven justices who said that there’s a trust responsibility between tribes and the federal government and states don’t have any say in this,” he explained. “That was the crux of the argument that states have jurisdiction in adoption cases.”

Nez said political ideology should not be included in these decisions.

“So, with the seven justices who supported Indian Country, it’s a great win for our children,” he added.

The Indian Child Welfare Act, the 1978 law, was meant to address the legacy of abuses of Native children who had been separated from their tribes to be raised by non-Native families without connection to their culture and traditions. Specifically, the ICWA targeted the forcible removal of Native children from their homes and restricted the adoption process. When Congress passed the act, it wanted to uphold the best interests of those Indigenous children but also keep in mind the preservation and history of tribes.

President Buu Nygren said over 600 Diné children in the Nation cycle through foster care. And the tribe’s adoption unit within its ICWA Program promotes the permanent placement of Diné children in Diné homes for preservation and cultural identity.

“That’s the thing I think about––is revamp our own system on our own side, is to really see and to make sure we have enough Navajo foster parents, foster families so that they can actually take care of the kids,” Nygren said in an interview with the Times Thursday afternoon. “That’s one of things I’ve tasked (executive) director (Thomas) Cody (of the Division of Social Services) on: let’s revamp ICWA within our own department so that we can start preparing families to adopt kids.”

Nygren said he’s pleased the Supreme Court upheld ICWA, which was intended to rectify past government abuses.

Foster care system

Before the ICWA, many Native children were being wrongfully taken from their homes and placed into adoption agencies.

Stephanie Benally, the Native American specialist for Utah Foster Care, said that when it comes to a child’s welfare, a judge is charged with determining the child’s best interest. Under the ICWA, Native children are subject to different rules to safeguard their tribal ties.

“When a child comes into (foster) care, the first placement preference is kinship,” Benally explained. “Second placement is a licensed Native foster parent of the same tribe. Third is a licensed Native foster parent from a different tribe, and the fourth is open to any available foster home.”

“We will continue as we’ve done in the past and now, going forward, to continue to try to find those ICWA-compliant homes for our kids in care,” she said. “So, sharing that message: there’s a shortage. People who are interested, they can contact their state or us or their tribes in becoming licensed foster parents because if our kids don’t have those Native foster homes when they come into care, they’ll either go into a non-Native home or into a shelter. We want to make sure our kids are staying within our Native community.”

Benally said when a Native child is placed in Utah Foster Care, it will return to the child’s birth parents or relative.

“That’s important because if they’re not able to go the birth parents, then at least they’re going to a family that has that judge history––cultural connection, so there’s that high rate for verification to happen,” she explained. “And that’s the number one goal when a child comes into care.”

For kids placed in Native homes, the cultural connection and the language are easily accessible.

“We have Native foster parents who provide that every day to our Native kids that are in their homes that they’re caring for,” she added. “It’s not something where they just take them to a powwow or read a book to them. It’s everyday support: talking to them about cultural information at the dinner table or taking them to activities in the community to help them connect.”

Benally is Deeshchii’nii and born for Tódích’íi’nii.

If ICWA was overturned

If the Supreme Court had decided to overturn the ICWA, states would have regained the control to remove Native children from their families.

Former Speaker LoRenzo Bates said that each time a Native tribe went to the Supreme Court, it got beat.

“The tribes got beat,” Bates said in an interview Thursday morning. “Would this be another situation that would go against us? Everyone had that same thought. We (didn’t) know.

“The delegates, the Health, Education, and Human Services Committee would go to D.C.; that was one area they would advocate for, with D.C. leadership.”

Bates said when he would ask HEHSC what the response was from the federal government, it would be, “We don’t know what to expect either.”

“So, even that supported where we were coming from as a Nation––is we didn’t know,” he said. “But most importantly, it needed to be in favor of all Indian nations across the United States. It needed to go that way.”

Bates said when he read the last paragraph of the ruling today, Justice Samuel A. Alito said it all as to why Congress put the ICWA together: it was given to the tribes to go in that direction.

Alito said he’s sympathetic to the challenges tribes face in maintaining membership and preserving their cultures.

“And I do not question the idea that the best interests of children may in some circumstances take into account a desire to enable children to maintain a connection with the culture of their ancestors,” Alito stated. “The Constitution provides Congress with any means for promoting such interests. But the Constitution does not permit Congress to displace long-exercised state authority over child custody proceedings to advance those interests at the expense of vulnerable children and their families.”

“It said it all in that one paragraph,” Bates said. “His (Justice Samuel A. Alito) thoughts and today––we flipped our thoughts back then. So, he understood.”

Read more in the June 22 edition of the Navajo Times.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow