50 Years Ago: Giving Navajo youth power and remembering a Navajo casualty of the Vietnam War

There is no historic record on who came up with the idea, but it appears that sometime in early or mid-1960, someone in the Bureau of Indian Affairs got the idea on how to change the future for the Navajo Tribe.

The idea, according to news articles at the time, was to bring together some of the best Navajo students going to BIA schools, as well as public schools, and give them the encouragement necessary to give them the incentive to take a careful look at the problems facing the tribe and, at some point in their future careers, to come up with solutions on how to solve them.

A few of the students came from off-reservation schools from places like Salt Lake City and Anadarko, Okla. In early December 1965, the BIA held its sixth annual Navajo Youth Conference, bringing together some 250 Navajo students from all over the United States to the Fort Wingate High School. The president of the Navajo Youth Organization, as it was called, that year was Angelo John from Flagstaff, who was a freshman at Arizona State University. One of the event’s coordinators, John C. Martin, said he had high hopes that those students who were invited to the conference to listen to speeches from experts in a number of fields would become the future leaders of the tribe. It was hoped, he said, that Navajo youth will be able to recognize these problems and to make every effort on their own to solve these problems.

So even back in the 1960s, government leaders recognized the fact that Navajo youth had the ability to shift through the political rhetoric that created problems within the federal and tribal government, and to help create solutions. One of the main supporters of this idea was Mack Easley, the lieutenant governor of New Mexico in 1965. He was to be one of the speakers during the conference, giving a speech on Navajo Youth and the Modern Age.

It has been my observation that the Navajo boys and girls, in particular, possess qualities of stability, mental alertness and dependability, which will make them the leaders of tomorrow,S he said.

A couple of interesting observations can be made some 50 years later.

First, even though everyone in the 60s had such high opinions of Navajos in their teens and 20s, leaders of the Navajo Nation, the future chairman and presidents, were already in power and would stay in power for the rest of the century. While those who attended the conference may have had ideas on changes they would like to see made in the tribal government, the people who were chosen to be the division directors of the tribe and to lead the tribe in the future came not from the people who attended these conferences and had ideas on how to change the government, but people who were loyal supporters of the winning candidates during their campaigns.

It wasn’t until this year, in fact, under the administration of Russell Begaye that a winning candidate surprised the voters and actually went out to seek the best Navajo minds he could find to fill the division director posts. Another observation over the years was that while tribal leaders would often say they would seek the advice of the best and brightest among the Navajo youth when they had the opportunity to do that, but they often found this could create problems.

A case in point were the efforts by Peter MacDonald in the 1970s when he was chairman and created the Navajo Youth Council, the first real pilot experiment to give Navajo youth some say in how the tribal government was run.

MacDonald discovered after the youth council was in existence for a couple of years that Navajo young people had a great deal to say about how the tribal government was being run and were very vocal in their observations; so vocal that the youth council became a political liability and it was eventually disbanded.

The good thing about the student conferences that were held in the 1960s and the youth council in the 1970s was that they created a way for Navajo youth to get really involved in the operation of their tribal government, and while it may not have created a lot of tribal leaders, it did form the basis of what would become a vocal group of Navajo advocates for governmental change.

Also in the news, officials for the U. S. Department of Defense announced in early December that a second reservation resident was killed in the growing conflict in Vietnam.

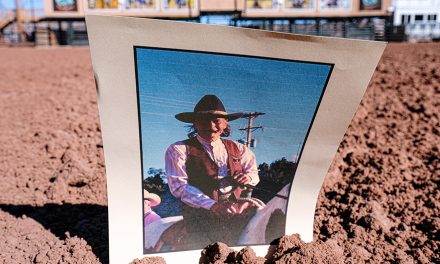

Marine Corporal Warren L. Dempsey of Churchrock died on Dec. 2 in the crash of his aircraft while under enemy fire. Dempsey was a gunner on a military helicopter. The first casualty of the war from here was Marine Alvin Chester of Window Rock. Dempsey was the son of Alfred and Joy Dempsey of Church Rock, N.M.

A graduate of Gallup High School, he was 25 at the time of his death. His survivors included three brothers – Gordon Dempsey of Window Rock, Alfred Dempsey Jr. and Lee Dempsey, both of Churchrock. He had one sister, Gloria Dempsey of Ganado Mission.

To read the full article, pick up your copy of the Navajo Times at your nearest newsstand Thursday mornings!

Are you a digital subscriber? Read the most recent three weeks of stories by logging in to your online account.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow