50 years ago: Medicine men note fewer apprentices

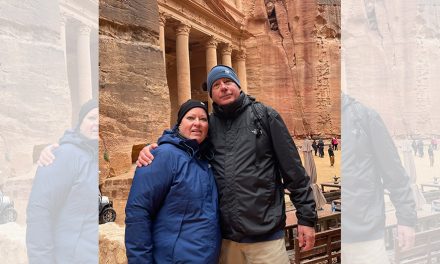

Raymond Nakai and Robert Kennedy in about 1960. Image courtesy of Navajo Nation.

It turned out that 1968 and 1969 were watershed years in the history of Navajo culture.

We learned this in the late 1970s and early 1980s when officials for the Diné Medicine Men Association began noticing a drop in the number of young Navajos signed up to apprentice with elderly practitioners.

At the time, officials for the association said they began seeing the problem in the late 1960s as the chairmen of that era — Raymond Nakai and Peter MacDonald — started urging Navajos in high school to go to college and get a good job that paid a decent wage. MacDonald, who said that in his early years he considered becoming a medicine man, especially geared his education program to creating Navajo professionals.

As the job market improved and the military began making a bigger effort to get high school seniors to volunteer for the service, the number of Navajos going into the traditional practices seemed to get smaller each year. Becoming a medicine man required years of learning, being trained by one who had been in the profession for decades. The pay was low — often in the form of barter rather than money — and benefits such as paid vacation didn’t exist.

For the most part, it took a calling, and the association said that as the reservation became dominated by the non-Indian culture off the reservation, fewer and fewer Navajos seem to hear the call. It got to the point where in a few years, the Indian Health Service and then the Navajo Nation would have to step up and establish their own programs in order to encourage more Navajos to become apprentices. Under these programs, the medicine man who agreed to take on an apprentice would receive a monthly stipend — $300 in the 1970s — and the apprentice would receive the same, with the mentor being required to report in periodically on how well the apprentice was doing and announce when the person had reached the point when he could go out on his own.

IHS officials were proud of the program and it received a lot of publicity during the several years it was in operation. The National Enquirer even did a major article on it in the mid-70s. Neither the IHS nor the tribe ever released figures on how many new people graduated from the program or how many stayed on after the first several years.

By the 90s and early 2000s, the Navajo Times continued to report that most of the practicing medicine men were in their 60s and many were refusing to take on new apprentices because many in the younger generation continued to shorten the ceremonies and only seemed interested in learning the more popular ceremonies, causing concern that some of the lesser ceremonies may be lost forever.

Raymond Nakai and Robert Kennedy in about 1960. Image courtesy of Navajo Nation.

In other news, I’ll bet if you are over the age of 60 you will remember what happened exactly 50 years ago. U.S. Sen. Robert F. Kennedy flew into Window Rock — hoarse and sunburned, according to the front-page article in the Navajo Times — and gave a scorching speech criticizing the BIA boarding school system. Kennedy was running for the Democratic nomination for U.S. president and was just nine weeks from winning the California primary and being assassinated.

Speaking at the 11th annual Navajo Education Conference at the Window Rock Civic Center, Kennedy said the boarding schools took away Navajo children from their parents at the worst possible time, downgraded Navajo culture and dampened the students’ will to learn. “As one teacher puts it,” said Kennedy, “the white man in the United States doesn’t know what he is doing to the Indian student.”

The fact that Kennedy took time out of his busy schedule came as a surprise to many because he was in a tight race for the nomination and only a small percentage of Navajo adults were registered to vote at that time. Kennedy called it a “national disgrace” that 60 percent of Navajos who go to college drop out in their first year. “It’s time that the Indian take over their own education,” he said.

Dick Hardwick, the general manager and editor of the Navajo Times, wrote the front-page story and said Kennedy put away his prepared speech and spoke off of the cuff. His planned speech was nowhere near as critical of the BIA, said Hardwick.

Why the change? Hardwick said it may have been due to the introduction that Navajo Tribal Chairman Raymond Nakai gave him, needling him by calling him a “modern David” fighting the antiquated beliefs of a failing education system.

Kennedy noted that two Navajo students had run away from their boarding school the past winter and one had died. He call this “shocking” and said it was a good example of why the boarding school system was a failure. Kennedy said it was time for the federal government to take a realistic look at the failures of the current Indian education system and replace it with one that is worked out with the Indian people, one that would take into consideration both age-old traditions and modern-day approaches to education.

To read the full article, pick up your copy of the Navajo Times at your nearest newsstand Thursday mornings!

Are you a digital subscriber? Read the most recent three weeks of stories by logging in to your online account.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow