50 years ago: Memories of Long Walk, captivity still linger

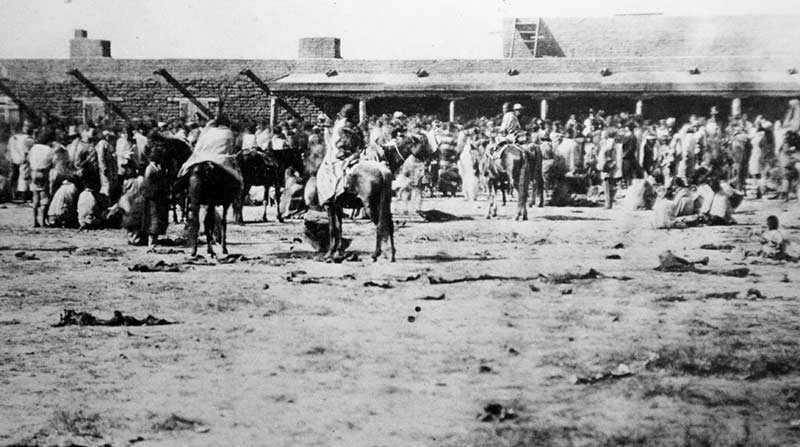

Navajos at Fort Sumner, New Mexico, 1864.

The Navajo Tribe was seeing a lot of interest among tribal members who wanted to participate in one way or another in the 100th anniversary celebration of the signing of the Treaty of 1868.

This included thousands of Navajos who said they wanted to honor their grandparents or great-grandparents who actually went on that walk a century ago, and who said they still remember the stories they were told about the walk and the years their ancestors spent in captivity at Fort Sumner, New Mexico. The Navajo Times reported in its coverage of the planned Long Walk re-enactment that for many Navajos, the events of a century ago still had a major affect on their lives.

“The memory of the Long Walk and years of captivity still linger!” said the Times article. The big problem for the tribe was how to allow everyone who wanted to participate a chance to do so.

The tribe had provided food and supplies to allow 150 Navajos to take part in the re-enactment, but then said that anyone who wanted to join the march and walk for a short distance could do so.

The re-enactment included parades through downtown Albuquerque, Santa Rosa, Grants and Gallup as well as re-enactments of the signing of the Treaty of 1868. As to who would be among the 150, tribal officials said they wanted the walk to be as authentic as possible, so participants would be asked to dress traditionally or as Navajos did in those days.

Organizers of the event said preference would be given to Navajo men who still wore their hair long in the traditional Navajo style. Also each district would be given a certain quota so all areas of the reservation would be represented. The Navajo Times also announced that it would put out a special edition to celebrate the event with numerous articles on Navajo history and culture by both Navajo and non-Navajo writers.

The result, said the Times, should be a special edition that will become a keepsake.

In other news, the Times took note of the third anniversary of Rough Rock Demonstration School, praising its commitment to preserving traditional values and educating Navajo children in a traditional way.

The school had 300 students from kindergarten through the 7th grade that past year and another 300 in its adult education program. The Times also noted that the school received a federal grant that provided it with twice as much money as a BIA boarding school of that size would get. To understand why Rough Rock is so important to Navajo education, the paper said you have to understand how most Navajo parents felt about education after the Long Walk.

The efforts by agents for the federal government to get parents to send their children to federal boarding schools in the 1870s and 1880s was an “utter failure,” according to the Times. Navajo families did not trust the government and felt if they sent their children to federal schools they would lose them, and there wasn’t much the federal government could do to change their mind. It didn’t help that many of those Navajos who did go to school later turned their back on Navajo tradition after being taught by white teachers for years that tradition was bad and they should convert to the Anglo culture.

By 1965, both the BIA and public schools had gained power but many Navajo families still believed that the schools were causing their children to abandon their traditional ways so a school like Rough Rock was considered very special in their minds. The paper predicted that Rough Rock would set the stage for the creation of schools of a similar nature throughout the reservation and that the next generation of Navajos would how to schools that promoted both cultures equally.

That issue of the paper also included remarks by U.S. Sen. Robert Kennedy, who had spoken at a Navajo education conference and sharply criticized the federal government for failing to educate Indian children.

This can be easily seen, Kennedy said, by the fact that Indians who graduate from schools earn 75 percent less than non-Indian students and their life span is considerably less because of the poor health care provided by the federal government.

The dropout rate of Indian students is twice the national average, he said, and they are being taught by non-Indians who are indifferent to their problems. He said his visit to the schools on the Navajo Reservation recently were an eye-opener for him and other members of his delegation. He said he didn’t have much hope that things would change in the near future because the federal government was reluctant to change its approach to the way Indian children were educated.

What is needed, he said, is a total rethinking of the way the federal government approaches the education of Indian children. As part if this, he said, the federal government needs to spend more time listening to parents and Indian governments. Kennedy was at the time running for U.S. president and he was shot on June 5, 1968, and died the next day, ending his plans for changing the way Indian children were being taught in BIA boarding schools.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow