50 years ago: Nakai takes control of advisory council

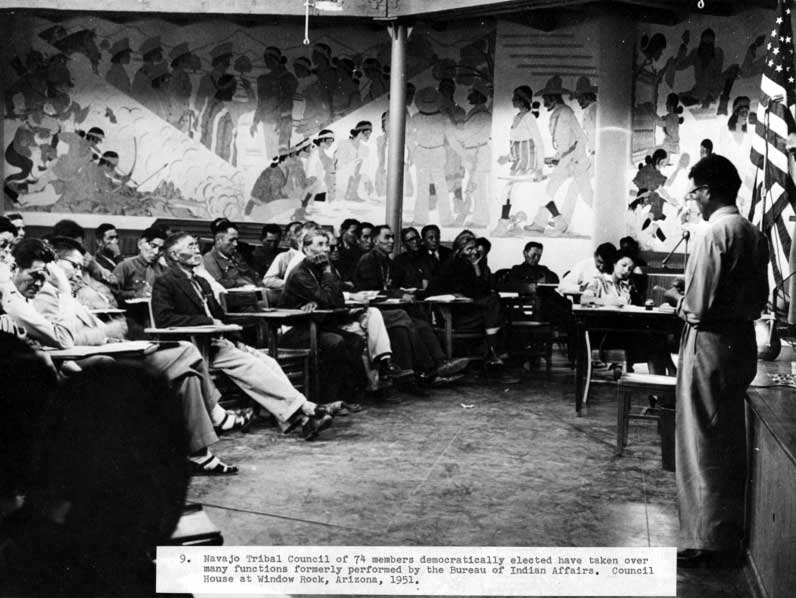

The Navajo Tribal Council originally consisted of 74 elected members who took over duties that had been performed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. (Photo of Council in 1951 courtesy of Truman Library.)

This was everything that Raymond Nakai believed being chairman would be.

After four years of being a chairman in name only, Nakai, in the first week of his second administration, finally had the power to be chairman with a 31-30 vote to be allowed to pick members of the council’s advisory committee.

Under the old system of tribal government, having control of the council’s advisory committee, which was the most important of all the committees, basically meant you were in control of the council and the tribal government.

Being able to name enough of his supporters to the committee to make sure the committee did what he wanted meant he would control the agenda of the council for the next four years. He would be able to control what issues went before the council and, to some extent, who would be in control of the other committees.

More importantly — and this would be recognized by his successor, Peter MacDonald — controlling the council also allowed you to have control over the tribe’s money and as chairman, you would have a big say on what chapters got what funding for what projects.

For the first time, council delegates who were part of the Old Guard and who opposed Nakai found themselves being shut out of being able to get projects funded for their chapters and early on in Nakai’s second term, many of those who had opposed him in the first term came over to his side because they could not risk going into their next election without having any projects approved for their chapters.

Yes, delegates like Annie Wauneka refused to back down, but for those who only supported the Old Guard because they were in power, switching over to Nakai didn’t seem to be that big a thing.

That part of the old system was one of the big reasons why in 1990, a decision was made to abandon that system of government because it gave one person, the chairman, too much power. He would control all three branches and there would be no check and balance so in 1990, the chairman was stripped of his ability to control the council and, as president, lost a lot of his power to bring about change.

Chet Macrorie, the managing editor of the Navajo Times (for the second time), knew that week that his days at the Times were numbered.

Not only did Nakai hate the tribal newspaper (he had not given a Times reporter an exclusive interview in more than three years but during his campaign, he would often tell his supporters not to believe what they read in the Times and in other newspapers that covered reservation events.)

Believe what you hear on the radio, he would say, indicating that the radios were more truthful than the newspapers when in reality, none of the radio stations that broadcast near and on the reservation had news departments and what they relied on was press releases from the chairman’s office and radio messages, often on a weekly basis, that came out with Nakai giving the news of his administration to the Navajo-speaking members of his tribe.

Within days of Nakai’s inauguration, Macrorie would later say that he found himself under attack from Nakai and others in his administration.

He would later say that one official came to him and said he wanted a system devised where he would be able to see any article dealing with the tribal government before it was published.

Macrorie said he was told that the officials would not try to censor what got in the paper but he only wanted to know what was being said so he could be sure that Nakai’s side would be included in the article.

Macrorie said he turned the offer down, realizing that this system would quickly evolve into a “No, you cant run that article” situation.

Once that happened, he said, the Navajo Times would lose all credibility and it would be no more than a newsletter run by the chairman’s office. He vowed he would fight it as long as he was there.

Speaking of MacDonald, another big reason why he was able to defeat Nakai in four years was announced this week.

The U.S. Department of Labor announced a $556,300 grant to the Office of Navajo Economic Opportunity for its Neighborhood Youth Corps program.

This was a wildly popular program during the 1960s because it provided funds to hire some 500 in-school students and 650 students in the summer to do jobs for the chapters and other government agencies.

MacDonald was in charge of the program and although Nakai was a supporter, most of the credit went to MacDonald and many of the high school students who would soon be 18 and of voting age heard about MacDonald for the first time when they participated in the program.

Whether he realized it at first or not, being head of this program provided MacDonald with a tool to get students on his side with the hopes that they would be able to persuade family members — who were probably Nakai supporters – to a least listen to what he was saying when he ran in 1970.

To read the full article, pick up your copy of the Navajo Times at your nearest newsstand Thursday mornings!

Are you a digital subscriber? Read the most recent three weeks of stories by logging in to your online account.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow