A difficult, rewarding, sacred life

Robert S. McPherson, “Navajo Women of Monument Valley, Preservers of the Past” (distributed by Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2021)

By Lee Bennett

MONTICELLO, Utah

Navajo women today have a proud heritage that parallels that of Navajo men, as both follow traditional roles specified by the holy people.

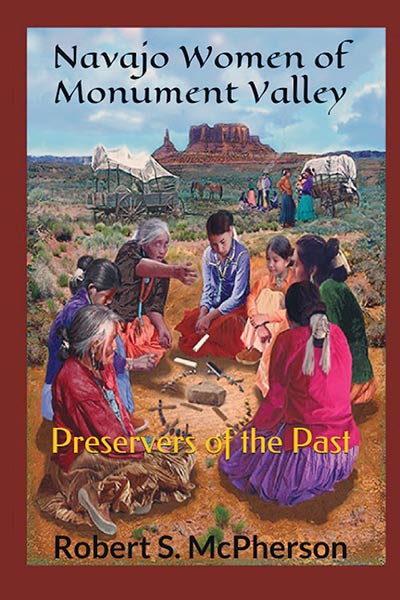

Book cover for “Navajo Women of Monument Valley, Preservers of the Past” (Robert S. McPherson, distributed by Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2021)

Yet far more information has been published about the activities and teachings of men than that of their female counterparts. There are a few exceptions, such as Charlotte J. Frisbie’s “Tall Woman: The Life Story of Rose Mitchell.”

In McPherson’s book, “Navajo Women of Monument Valley, Preservers of the Past,” a variety of women’s voices tell their story of what it was like to be raised in the first quarter of the 20th century, when the livestock industry flourished, ceremonial practices were at their height, cultural teachings prevailed, and the clan system was a powerful, uniting force (k’é).

Their stories share similarities, not just because they were from the Monument Valley area, but because they followed the teachings of their elders.

For those interested in what life was like a generation or two ago, the reader will find a personal, oral history approach to what they encountered. Collected more than 30 years ago, their words tell the story of a difficult life that was both rewarding and sacred.

While 18 different women share their experience and insight, there were two – Ada Black and Susie Yazzie – who provided detailed descriptions about their lifetime.

Both women were raised in traditional Navajo homes with each witnessing many changes that brought wonder and worry. Their stories are woven together with the memories of the other women to offer a fascinating, often poignant, look at the importance of the female role in Navajo culture.

Behind each memory and story are sacred teachings learned in childhood and practiced daily.

The women discuss the application of traditional teachings to puberty, birthing, the division of labor between men and women, the importance of their flocks, and the devastating consequences of the federal livestock reduction program.

They talk about the impacts of uranium mining, reliance on traders and trading posts, transference of travel rituals from horse to auto, and the double-edged sword of educating Navajo youth in Anglo schools.

I really enjoyed this book and appreciate the different perspectives offered by the women. I also found in their concerns a common thread that binds generations together, the admonition to live life properly to assure that grandchildren will have a respectable and secure life.

Indeed, one of the primary reasons that these women shared their experiences was for their posterity – children, grandchildren, and future generations beyond – to understand what it means to be Navajo and a woman living in the shadow of Changing Woman.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow