Boarding school survivors who shared their stories nearly two years ago get apology from Biden

Navajo Times | Donovan Quintero

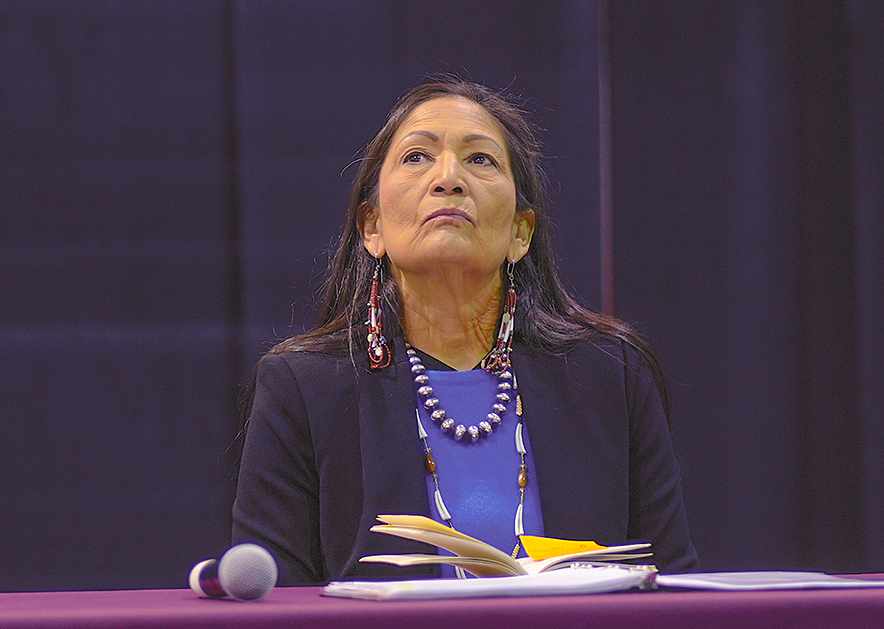

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland listens to Navajo Nation boarding school survivors, recounts their experiences during her “The Road to Healing” tour on Jan. 22, 2023, in Many Farms, Ariz.

WINDOW ROCK

She and her siblings grew up in Black Mesa and Dinnebito, Arizona, and grew up very traditional and lived in a hogan.

From an early age, every morning they were made to run with their corn pollen pouches. They ran to the east, up to a little tree and there they made their offerings. Then they ran back to the hogan to start their day.

Her daughter, Eleanor Smith, said she had a very traditional upbringing. She prayed every morning.

Navajo Times | Donovan Quintero

Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs, top left, sits next to President Buu Nygren during Interior Secretary Deb Haaland’s “The Road to Healing” tour on Jan. 22, 2023, in Many Farms, Ariz.

It was sometime in the 1940s when Smith’s grandparents, her mother’s parents, saw a BIA truck and a black car with white stars on its doors pull up to their hogan.

A Navajo Police officer, acting as an interpreter for the BIA official, told them to put their fingerprints on a document that would send their children off to a boarding school, or face the consequences if they didn’t.

“You have to put your fingerprint on this document to send your kids away to boarding school. If you don’t, you will be arrested and you will be taken to jail,” Smith recounted the story of her mother’s boarding school journey that led to forced assimilation and forced atonement because of her traditional Navajo beliefs.

A mother’s story, emotional scars

Smith shared her mother’s painful story of being forcibly taken from her family to attend a government boarding school, echoing the traumas faced by many Navajo children during that era.

Eleanor recounted the harrowing moment when her mother and her siblings were separated from their parents.

“My grandparents, not having many options, went ahead and put their fingerprints on there,” she recalled. This decision led to a devastating consequence; Eleanor’s mother and her siblings were forcibly removed from their home, a traumatic experience that still resonates within their family.

“The pain of that moment is unimaginable,” Smith reflected. “I can just imagine the trauma that they had to go through.”

She described how her mother and her siblings were taken to an unfamiliar environment, speaking only their native language and possessing no understanding of the culture they were thrust into.

Smith painted a vivid picture of the fear and confusion experienced by her mother and her siblings as they were loaded into the truck, their cries and screams for their parents echoed in Eleanor’s voice as she became emotional resharing her mother’s childhood ordeal, encapsulating the deep emotional scars left by the boarding school system.

“Not knowing one word of English yet being forced to speak it. Not knowing a culture, a foreign culture, yet having to conform to it. Not knowing a foreign place that they were being taken to,” Smith said.

Smith recounted the traumatic experience her mother endured when she and her siblings were forcibly taken from their home.

“They were loaded into a truck, crying and screaming for their parents,” Smith recalled. “My mother said they huddled together for comfort, surrounded by some cousins who were also in the truck. They had no idea where they were going, only that they were headed to Albuquerque Indian School.”

Dehumanizing process, tádídíín tossed away

Upon arrival at the Albuquerque Indian School, located in Albuquerque, the children faced a shocking and dehumanizing process.

“They were stripped down for inspection and had their hair checked for lice,” Smith explained. “In our Navajo culture, hair is sacred; it’s intertwined with our spirit and identity. But in an instant, that was disregarded—they chopped off their hair without consent.”

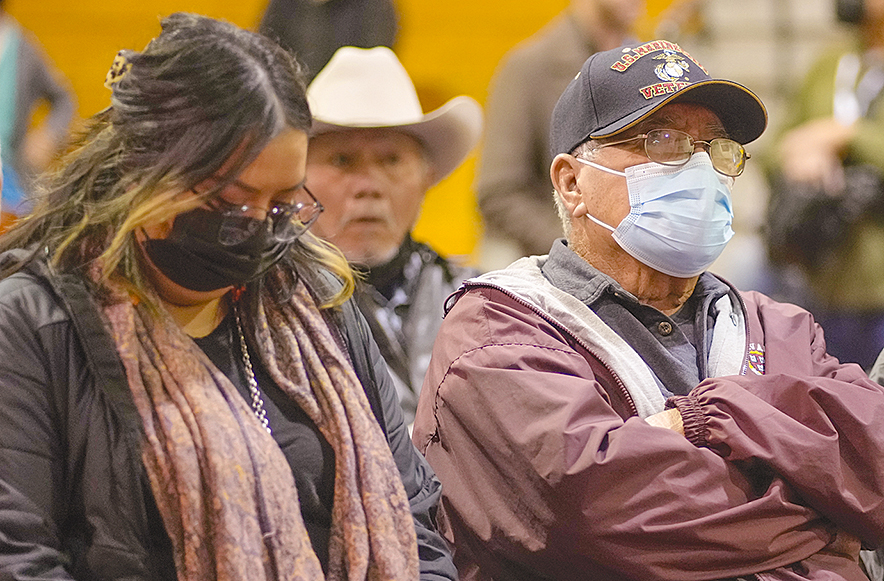

Navajo Times | Donovan Quintero

Navajo community members listen to Navajo Nation boarding school survivors and share their stories with Interior Secretary Deb Haaland’s “The Road to Healing” tour on Jan. 22, 2023, in Many Farms, Ariz.

Her mother’s tádídíín was also tossed away without much thought or consideration.

“Their corn pollen pouches are taken away and thrown in the trash,” said Smith.

Smith said her mother remembered her cousin’s sister getting furious at the dorm staff, who were also Navajo, for allowing such disrespect. She confronted them in Navajo, expressing her anger and pain at what was happening to them.

Her anger fell on deaf ears.

“These are the things that happened to them,” she shared on Jan. 22, 2023, with Department of Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, who was on “The Road to Healing” tour last year that allowed Indigenous boarding school survivors to share their stories.

Smith continued, “Not long after my mom got there, she contracted tuberculosis and was sent away to Santa Fe to the sanatorium, where she spent the whole school year.”

As she shared her mother’s experience, the pain was palpable.

“She had to have surgery to cut off a part of her lungs where she had tuberculosis, and she said she was so lonely there. The only people who would come visit her were like the Mormon missionaries, trying to comfort her,” Smith said.

The isolation her mother experienced was compounded by false reassurances, telling her that her parents would arrive soon to see her before her surgery.

“‘They’re gonna come see you,’” Smith shared with Haaland. “So, she went ahead with the surgery because they reassured her, but her parents never came. She stayed there even beyond the school year into the summer until they finally let her go home.”

When it was time for the following school year, Eleanor’s mother, along with her cousins and siblings, made a pact.

“They all got together and said, ‘Let’s all go to one school. We don’t want to be separated for this next school year.’ So, they decided to go to Chemawa Indian School,” Smith said. “When the BIA came to ask which school they wanted to attend, they replied, ‘We want to go to Chemawa,’ despite not knowing where it was.”

Homesick, moving home

Smith reflected on the education her mother received at the school, which is in Salem, Oregon.

“It was not like a regular education; it was made to be more vocational. My mom was trained to be a maid. Basically, she chose homemaking as her career path,” she explained.

After graduation, Smith’s parents moved to Seattle, where they met and started their family.

“My dad helped build the Space Needle, and my mom worked for a lawyer and a doctor, raising their child,” she shared.

But eventually, homesickness drew them back to the reservation.

“My mom was so homesick for her homelands, so we moved back. By that time, there were six of us that grew up together in Teec Nos Pos.”

Turning to her own boarding school experiences, Smith recalled, they didn’t have the option of being day students despite living less than a mile from the school.

“They told us we had to stay in the dorm. So, at five years old, I went into the dormitory,” Smith remembered.

She shared her own stories of abuse at the hands of a dorm aide, who she accused of spreading lies that she used the bathroom on herself in her bed or having her hair yanked and hit over the head while hair was being braided.

“She would take off my sheets and wake up everybody and say, ‘This girl is a bed wetter,’ and show everybody the sheets were there was a wet spot and in my pajamas were dry,” said Eleanor of the false accusations the dorm aide said about her.

Eventually, another dorm aide informed the school of what the dorm aide was doing. Her mother was asked what appropriate action the school take could. She said she opted the dorm aide be given

“But she spoke from her heart, and she scolded this lady in Navajo, but the way she did it was more like getting after her and in a good way not in a bad way. She told her, ‘I have mercy on you, and I think you should go with the leave without pay,’” Eleanor recounted her mother’s decision, and told the school, “‘I don’t want to fire her.’ And so that’s what they did.”

Recounting experiences

Haaland quietly listened the whole time as she did with other boarding school survivors who recounted their experiences. Before recording the testimonials, she told the audience she would “weep” with them as they shared their pains.

“Your voices are important to me. We all carry that trauma in our hearts. My ancestors and yours endured the horrors of the Indian boarding school assimilation policies carried out by the same department that I now lead,” she said at the time in January 2023 in Many Farms. “This is the first time in history that the United States Cabinet Secretary comes to the table with the shared trauma that is not lost on me and I’m determined to use my position for the good of the people.”

The effort – the first of its kind, undertaken by the federal government – was part of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative launched by Haaland.

The initiative marks the first comprehensive effort by the federal government to confront and address the harrowing legacy of past Indian boarding school policies that have impacted children like Smith’s mother.

Other former boarding school students like June Marie Wauneka and Ernest Dick Sr., also shared their stories with Haaland.

“I didn’t want it, and they told me, ‘Well, you’re going to have to eat it.’ So, they saved it for me the next day. They served it in different food, and I had to eat that sauerkraut,” Wauneka told Haaland in January 2023, who lives in Cedar City, Utah.

Like Eleanor’s mother, she too had her cut off, she said. However, Wauneka, said the school separated her from her siblings and wouldn’t allow them to see one another.

Ernest, from Rough Rock, Arizona, said they were made to drink spoiled milk. And if they threw it back up, they made them drink another one.

“I’m not lying. You throw it back up they give you another one. So that was terrible,” Ernest shared with Haaland. “Who wants a drink spoiled milk?”

Lynette Willie shared a story of how her great-grandfather, as a young boy, was returning from Hwéeldi when he and the other Navajo children were separated from their families in Fort Wingate, New Mexico. Willie said he managed to escape.

When he got back to his family, they told him the Navajo people needed to do two things: the Navajo people needed to have children, and they needed to go to the white man’s school.

“Because if we have as many children as we can’t, the Navajo people will never die. Then he said, ‘We need to tell our children to get an education, learn of their ways, because that’s the only way that we’re going to defend ourselves,’” said Willie. “And so, they told my great-grandfather to go back to school. And that’s what he did. And he learned five languages.”

She said her great-grandfather later became a Navajo leader and an Army Scout.

“So, he got land that was given to him because he was part of that and got a Congressional Medal for participating in the Indian wars,” she said. “But these are some of the things that happen and that’s where the legacy of boarding school started.”

Detailed accounts, policy recommendations outline

DOI released the second and final volume of its investigative report, spearheaded by Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland. This latest volume builds upon the initial report released in May 2022, significantly expanding the scope to include detailed accounts of institutions, attendee deaths, burial sites, and the involvement of religious organizations. Moreover, it outlines policy recommendations aimed at Congress and the Executive Branch to support ongoing healing efforts and redress for affected Indigenous communities.

The newly published Volume 2 updates the official list of federal Indian boarding schools to include 417 institutions across 37 states and territories. The initiative reveals that at least 973 American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children perished while attending government-operated or supported schools.

The report also identifies at least 74 burial sites—both marked and unmarked—at 65 different school locations. Through extensive research, the report estimates that between 1871 and 1969, the U.S. government allocated more than $23.3 billion.

In their comprehensive review, the Department examined approximately 103 million pages of federal records. Secretary Haaland and Assistant Secretary Newland also engaged with government officials and Indigenous leaders from Australia, Canada, and New Zealand to gain insights into how they addressed similar issues stemming from boarding school policies.

In late 2023, Haaland and Newland concluded a historic tour titled “The Road to Healing.” This 12-stop journey across the country provided Indigenous survivors with a platform to share their experiences in federal Indian boarding schools, marking the first time many were able to voice their stories to the federal government. The events included trauma-informed support facilitated by the Department of Health and Human Services’ Indian Health Service and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Additionally, President Joe Biden has taken steps to bolster tribal sovereignty, designating sacred tribal lands as national monuments and implementing measures to combat violence against Indigenous Americans.

Historical injustices, wounds of past

Biden on Friday visited the Gila River Indian Community where he praised Haaland as a groundbreaking figure in his administration and reflected on the historical injustices faced by Native Americans.

In his remarks, the [resident expressed his gratitude for Haaland, the first Native American to serve in a presidential cabinet, and formally apologized.

“The federal government has never, never formally apologized for what happened, until today. I formally apologize as president of the United States of America for what we did,” Biden said Friday. “I have a solemn responsibility to be the first president to formally apologize to the Native people. It’s long, long, long overdue. Quite frankly, there’s no excuse this apology took fifty years to make.”

Secretary Haaland spoke about the historical injustices inflicted upon Indigenous youth, who were forcibly taken from their families to attend boarding schools from the 1870s to the 1970s. She remarked on the systematic efforts to “isolate children from their families and steal from them the languages, cultures, and traditions that are foundational.”

Haaland acknowledged that while the federal government attempted to “annihilate our languages, our traditions, our lifeways,” it ultimately failed in its mission to destroy Indigenous identities.

“But as we stand here together, my friends and relatives, we know that the federal government failed,” said Secretary Haaland.

In her address, Haaland emphasized the significance of an investigative report that calls for the federal government and Congress to undertake concerted actions aimed at healing the wounds of the past.

“We are already putting some of those recommendations into action through our interagency efforts alongside the Departments of Education and Health and Human Services,” she noted.

This includes significant investments in preserving Native languages and working on a decade-long national plan guided by tribal leaders and Native language teachers, which will soon be revealed.

Haaland touched upon the painful loss of Indigenous languages as a recurring theme in her meetings with survivors across the country.

“From Hawaii to Michigan to right here in Arizona, we are ensuring that our stories are told so that future generations can understand the impacts and intergenerational trauma caused by the boarding school policies,” said the secretary.

‘Road to healing’

Reflecting on her collaborative efforts with Assistant Secretary Newland, she mentioned their initiative termed “the road to healing,” which involved twelve visits to Indigenous communities. This allowed survivors and descendants to share their experiences and the lasting effects of the boarding schools.

Haaland also announced plans to finalize agreements with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and the Library of Congress to incorporate these oral histories into educational resources.

The announcement comes as Biden seeks to solidify his legacy in the closing months of his presidency. According to a White House press release, the Biden-Harris Administration has already outlined substantial investments made under his administration, totaling nearly $46 million directed toward Native American initiatives through the American Rescue Plan, the bipartisan infrastructure law, and the Inflation Reduction Act. These funds are aimed at improving infrastructure, ensuring access to clean water, addressing drought challenges, and expanding high-speed internet access within tribal communities.

Gila River Community Gov. Stephen Roe Lewis, who emphasized the profound significance of the moment, said the acknowledgment was the first step toward healing.

“We are here today to acknowledge the past and to take the first difficult, but necessary steps to begin the healing,” said Lewis. “Because today is as much about our future as it is our past. All of us present today are joined in spirit by those who did not survive the unmanageable.”

Gov. Lewis paid tribute to the lives lost to the systemic trauma inflicted by the boarding school system.

“We offer our prayers to those who did not survive, and we offer our heart to those who did as we admire their strength,” he stated, highlighting the resilience of Indigenous communities in the face of such adversity.

Nygren expresses gratitude

Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren expressed his gratitude last Friday for President Biden’s apology regarding the historical injustices of Indigenous boarding schools, emphasizing its significance.

“The apology was very significant because if it were easy, any previous presidents would have done it already. But we’ve never received an apology. It highlights the difficulty of this issue in U.S. history. Now, the most powerful person in the world has apologized. I’m sorry on behalf of the United States for the trauma that boarding schools inflicted on Indian Country, attempting to erase our culture and language, leading to the tragic reality that hundreds of children never returned home. For him to do that was incredibly honorable.”

Following a one-on-one meeting with the president, Nygren said he conveyed his appreciation and thanked Biden.

President Nygren said that while he was appreciative of Biden’s apology, much work was still left.

“When listening to his speech, I agree that much more needs to be done. We must ensure that this apology is meaningful, and now it’s crucial for him to align the Department of the Interior and the Department of Education to allocate resources that will help our people heal,” he said. “This responsibility falls on him over the next three months, and it’s important that whoever follows as President respects his decision so we can continue the healing process.”

Nygren concluded by reflecting on the importance of this moment in history, asserting, “These are historic times. The fact that the most powerful person is apologizing is something we can all be proud of as Indigenous people. Our voices are finally being heard at the highest level, and we are being taken seriously.”

Speaker Crystalyne Curley, who attended Biden’s visit, said that while the apology does not undo the generations of harm and devastation inflicted on Indigenous people, she commends President Biden for taking an unprecedented step toward healing and reconciliation.

“President Biden’s apology is a critical acknowledgment of past injustices and wrongdoings by the federal government, and it lays the groundwork for continued healing,” said Curley. “This moment is both a recognition of what our children endured and a commitment to a better future where our voices, cultures, and traditions are protected and celebrated.”

Biden’s presidency and political career which began in 1973 as a U.S. Senator for Delaware, recalled his own early experiences in the Senate, Biden shared personal stories and underscored the importance of recognizing the sovereignty of Native Nations.

“I was taught early on that it’s not ‘Indians,’ it’s ‘Indian nations,’” he said, adding that respect for tribal sovereignty has diminished over time, culminating in a history of broken treaties and forced removals.

The resident lamented the dark chapter of the Federal Indian boarding school era, which spanned from the 1800s to the 1970s, during which generations of Native children were forcibly removed from their families.

“We should be ashamed,” Biden stated. “A chapter that most Americans don’t know about.”

Nearly two years before, in Many Farms, Eleanor said she raised her own family and worked for the Bureau of Indian Education for 17 years.

“Throughout their school years, we see absent parents. Kids affected by alcohol and drug use, living with extended relatives … there’s just a range of trauma these kids deal with,” she stated, emphasizing the persistent cycle of hardship.

Having completed her master’s degree in multicultural education, Eleanor focused her thesis on an urgent issue.

“My thesis is titled ‘American Indian Intergenerational Trauma: Finding Paths to Healing.’ I believe we need trauma-informed education to address our students’ needs. We have to find ways to help them heal,” she asserted.

Eleanor advocated for returning to traditional practices.

“My mom taught me about the healing ceremonies for every season, which helps people cope with trauma. There’s not one fix-all program; we need tailored programs to meet individual needs,” she added. “Investment in counseling and support services is essential.”

She concluded her testimonial for her mother who she told Haaland now has dementia with a poem that ended with, “I’m ready to heal.”

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow