Code of the pawnshop

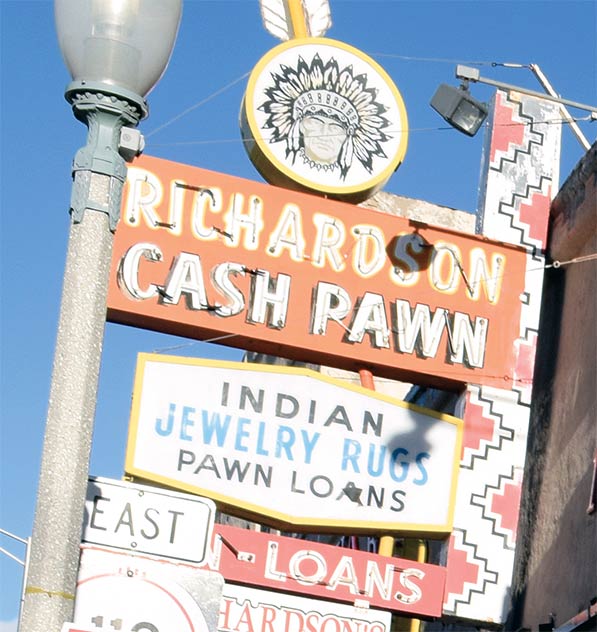

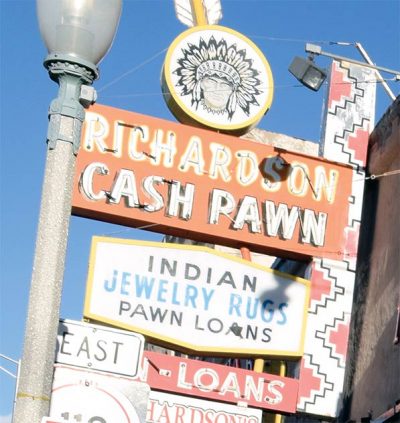

Navajo Times | Ravonelle Yazzie Richardson’s Cash Pawn is a well-known store in Gallup where for decades Navajo people have used their services.

Longtime traders stress fairness, accuracy and not selling off pawn

GALLUP

A few years before Bill RIchardson, the Indian trader and pawn dealer, died at the age of 98 in 2017, he was asked about the many items in his pawn vault.

Navajo Times | Ravonelle Yazzie

Richardson’s Cash Pawn is a well-known store in Gallup where for decades Navajo people have used their services.

At the time, people were estimating the items were worth $10 million or more. The items had been given to him by Navajo families over the previous five or six decades for safe keeping and had been stored away for the benefit of those families.

The families trusted Richardson, whose family had been in the business for more than 100 years, to keep their items safe and not to sell them even if they failed to show up when the pawn went dead and by law could be sold.

Richardson remained active in the business up until his death but as he grew older, the question would come up more and more: What would happen to the pawn in his vault when he was gone?

“There is no need to worry about that,” he would say. “I have made plans to make sure that the items in my vault will not be sold after I am gone.”

So in September 2017, just three months after his death, the tens of thousands of items in Richardson’s vault was transported quietly less than a mile away to the vault at Perry Null Trading Post.

After the transfer, letters were sent out to the people who had pawned their items and whose addresses were still valid. Flyers were also put up telling people who had pawned at Richardson’s that their item was now being handled by Perry Null.

And although both trading companies tried to inform everyone of the transaction, some were caught unawares.

One complaint

One woman from Continental Divide, New Mexico, complained to the Navajo Times this week about the transfer, saying she had not been told in advance and didn’t want her items transferred to Perry Null since her family had dealt with Bill Richardson for generations.

Refusing to make her name public, she said once she learned of the transfer, she went to the Perry Null Trading Post and paid for her family’s items and took them back to Richardson’s to have them placed back in his vault.

Since September, some Navajo families have done the same but most have allowed Perry Null to continue to hold the items for them.

Null was Richardson’s son-in-law and had worked in the Richardson Pawn and Trading Company for 25 years before starting out on his own and establishing his own business in Gallup.

“He trusted me,” said Null, and made arrangements when he died for Null to take over the old pawn business.

This, however, does not mean that Richardson’s Pawn is no longer in the pawn business.

Larry Fulbright, the manager of Richardson’s Pawn, said that as soon as the vault items were turned over to Null, the company began filling up its vault again with families bringing their pawn back to the company and by accepting pawn from others.

No selling of pawn

Over the past several decades, Richardson earned a reputation for not only selling pawn items when he had the opportunity but also for accepting items – like saddles – that others refused to accept because of the amount of space that the items took up.

In the winter, during the off-season, rodeo cowboys would pawn their saddles for safe keeping at Richardson’s, just as Navajo families have been doing for decades with their prized heirlooms.

Up until the 1970s, this was one of the main functions of trading posts on the reservation that accepted pawn.

Navajo families would pawn their most treasured jewelry and rugs, some of which had been in the family for generations, for a fraction of their worth just to have a safe place to keep them because of fears of break-ins at their homes.

Richardson often told the story of being in his store one day when a Navajo woman came in and pawned a beautiful turquoise and gold bracelet for $10. After she left the store, a tourist who had watched the transaction started criticizing Richardson for taking advantage of the Navajo customer. But Richardson explained the woman was only pawning it for safety.

Then when the items were needed for a ceremony or a festive occasion, she would come back and pay a dollar or two in interest, and then bring the item back a couple of days later when the event was over.

When the trading posts began closing down in the 70s and those still in business on the reservation stopped taking pawn, families began taking their business to off-reservation pawn shops. However, they found that most were not as honorable and once the pawn date had passed, would sell off the item.

Millions of dollars of old pawn came on the market in the 70s and 80s, lost to Navajo families forever.

A handful keep the tradition

But a handful of traders, including Richardson, kept up the tradition.

For many Navajo families on the reservation, the most trusted non-Navajos in the last century were Lorenzo Hubbell and Richardson.

Hubbell was an Indian trader who had a trading post in Ganado in the early 1900s. Before his death in 1930, he was the biggest trader on the reservation.

HIs trading post was eventually purchased by the U.S. National Park Service and is still operating as a tourist attraction and a community store in Ganado.

Hubbell, according to historical accounts, prided himself as being trustworthy and went to great lengths to prove to Navajo families they could trust him.

He would give Navajo families credit and on one occasion, a Navajo man came up to him and said the money the trading post said he owed was a penny or two too high.

Hubbell said he had no problem subtracting the amount from the man’s bill but instead he spent several days going through all of the receipts in the trading post for the past three months looking for his transaction and he was able to show the man that the store account was accurate.

Richardson was the same way.

In an interview in the late 90s, he took a reporter back to his vault and showed jewelry that had been pawned some 20 years before and had just sat there. The family had made no payment on the pawn in years but Richardson said he would never sell it because he knew that one day, the person who pawned it or another member of the family would come in and would redeem it.

Null said he learned from Richardson the proper way to handle pawn and he was going to keep those standards.

“I am not in the business of selling pawn,” he said.

To read the full article, pick up your copy of the Navajo Times at your nearest newsstand Thursday mornings!

Are you a digital subscriber? Read the most recent three weeks of stories by logging in to your online account.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow