‘Fighter for the land’: Klee Benally was a voice for kéyah, ‘ak’éí to many

Navajo Times | Krista Allen

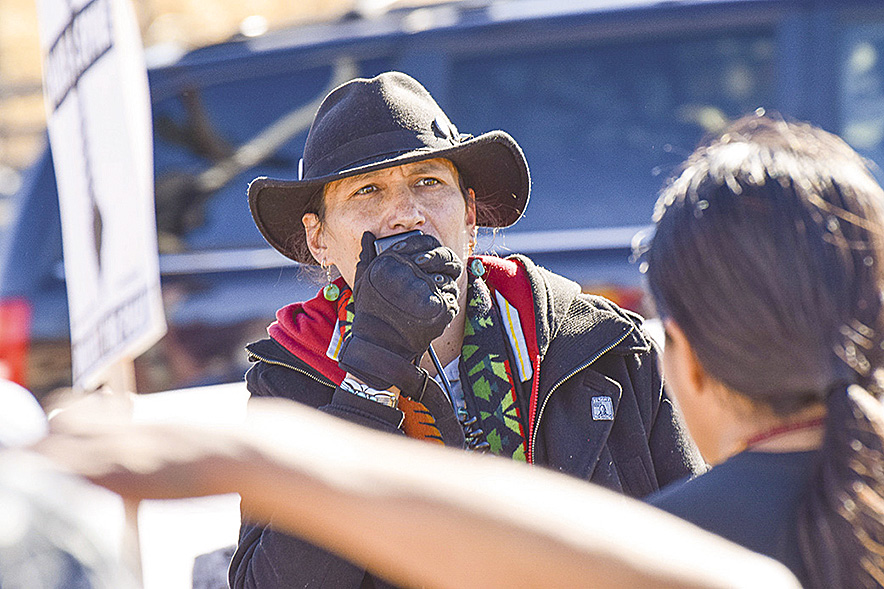

Klee Benally makes a statement during a demonstration in this Jan. 14, 2018, photo. Benally and others urged the Flagstaff City Council to end its contract with the Arizona Snowbowl Ski Resort, which uses effluent to make artificial snow.

KINŁÁNÍ – The late Klee Benally made his journey on Dec. 30 and is remembered by many as a fighter for the land and people.

“My brothers and I, we grew up on the hems of the skirts of our matriarchs who fiercely resisted relocation of our traditional homelands,” said Jeneda Benally, Klee’s older sister.

In the Big Mountain and Black Mesa area, Jeneda, Klee, and Clayson Benally were young children of Jones and Berta Benally, learning to stand firm using their voices as their matriarchs showed them.

Klee was Bi’éé Ł ichíi’ii and born for Tódích’íi’nii. His maternal grandfather is Polish, and his paternal grandfather is Naakaii Dine’é. Klee was married to Princess Benally.

For 48 years, Klee worked to protect not only his people and their land but Indigenous peoples far and wide and their land.

Navajo Times | Krista Allen

Klee Benally sings with demonstrators during a march across downtown Flagstaff in this Jan. 14, 2018, photo. Benally and others urged the Flagstaff City Council to end its contract with the Arizona Snowbowl Ski Resort, which uses effluent to make artificial snow.

“Everybody wants to know how he died, but I prefer to talk about how he lived,” said Jeneda.

The fire behind Klee’s actions began at his very own home on Dziłyíjiin.

“My brother laid his body on the line as he fought to protect Dook’o’oosłííd, and we were the youngest voices at the United Nations about how our water was being depleted by the Peabody coal mine,” said Jeneda. “There were so many victories, and anytime anybody stands up in the face of injustice, they are honoring my brother.”

The Peabody’s Black Mesa Mine, located on Dziłyíjiin, operated between 1965 and 2005 alongside the Kayenta Mine. The latter operated between 1973 and 2019.

Jeneda saw Klee’s dedication to advocating for the land and people as a “beautiful” way to continue his ancestors’ hard work in fighting for their land and people.

“My brother loved fiercely, and I think people misunderstood that his fierce love was a fierce anger,” said Jeneda. “His love was to create a world of respect.”

Klee was a strong-willed advocate most known for his work with “Protect the Peaks” and “Haul No!”.

Protect the Peaks is a movement dedicated to stopping the Arizona Snowbowl Ski Resort on the San Francisco Peaks, Dook’o’oosłííd to Diné, one of the four sacred mountains.

Klee and his siblings grew up knowing Diné culture and traditions as their father, Jones Benally, is a notable hataałii.

Sacred Dook’o’oosłííd

In an interview with the Navajo Times on Dec. 7, Klee expressed the disrespect that not only he felt but also other Diné and tribes who saw Dook’o’oosłííd as a sacred area, as taught to him by his father.

Not too far away from Dook’o’oosłííd is the Pinyon Plain Mine in the Grand Canyon, where currently advocates with Haul No! report, uranium is now being extracted and stock-piled at the Pinyon Plain Mine site.

Haul No! is a group spreading awareness about the Pinyon Plain Mine. In the Dec. 7 interview with Klee, he recalled the mine only being proposed and that it had not begun operation. But, in Klee fashion, he visited the site himself and took pictures of the mine.

‘It’s what Klee wanted’

Klee was a massive part of helping spread awareness and information on the harm done by uranium mines with Haul No!

In a post shared by Haul No! on the mine already extracting uranium, the post called for land protectors to help take action and shut down the mine because it’s what Klee wanted and worked for.

“Our grief and our sorrow should not make us complacent, but instead, it should uplift us in action,” said Jeneda. “I could talk a lot of our childhood, but my brother would be like, ‘We gotta talk about what needs to get done now.’”

As an older sister, Jeneda not only helped Klee protect and fight for the people and land but also made sure to protect and fight for her younger brother.

“I am flooded with so many memories, and I don’t want to forget a single one of them. I’m his big sister; I’m going to protect him,” said Jeneda.

Before Klee could put his entire being into protecting land, he made sure his voice was heard alongside his siblings in their band, Blackfire.

‘Blackfire,’ resistance

Blackfire was formed in 1989. It intertwined traditional Diné singing with an alternative punk rock base to make its frustrations about issues Indigenous people face known.

“We started playing music when the instruments were bigger than we were because we realized the power of music,” said Jeneda.

Jeneda remembers her father, who showed them that music can create change and be a powerful vessel.Not only did Jeneda’s father show them the strength of music, but their mother, Berta Benally, is a folk singer who taught the siblings about songwriting.

“So we started our band as a reaction to the anger we felt from the displacement of our people in the Joint Use Area,” said Jeneda. “A lot of people called us an activist band because of that––because every song we wrote together. As Blackfire, Klee, Clayson, and I talked about how we shared one brain that was huge for us that we shared so much.”

Because of the Peabody Western Coal Co. (Peabody Energy) settling on Navajo and Hopi lands, many families from both tribes were forced to relocate. Still, Klee and his family resisted the relocation and continued to reside in their traditional homelands.

Speaking out

In later years, while still keeping their traditional lands, Klee’s family moved off the reservation to Kinłání because Klee’s father didn’t want his children to go to boarding school like he did.

“Roberta Blackgoat was one of our grandmothers and Zonnie Benally, they were sisters,” said Jeneda, “and their voices, and particularly our grandmother Roberta’s voice, speaking out at protests was a huge part of my brother’s childhood and my childhood as well.”

The siblings grew up seeing their family use its voice at protests, speaking up about the injustices and inhumane conditions they were forced to deal with, which sparked the creativity among the siblings to start their band.

“Each song focused on different issues to bring attention to those different issues in hopes of sparking a realization within people that they could be the change,” said Jeneda. “If you know about it, do something about it; don’t just be complacent, be creative.”

Jeneda knows how fearless her brother was as he stood up to the people behind harmful actions to the land. She remembers how hardworking Klee was, always ensuring information was shared and people knew what was happening to the land they knew as sacred.

“I hope that the life’s work of my brother inspires every one of every age,” Jeneda said, “of every culture, of every standing to know that they have a voice to stand up and be that mouthpiece. Be a part of that process for social justice and environmental justice.”

Indigenous advocacy organizations recognize Klee’s dedication and are ensuring they continue the fight for the land that Klee showed them they can do.

Klee’s family knew him best and were amazed to see over 1,300 people show their appreciation for Klee at a memorial for him in Kinłání.

“My brother was my first best friend,” said Jeneda.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow