Six years post-Yazzie/Martinez ruling: educational disparities persist in New Mexico

Special to the Times | Donovan Quintero

Wilhelmina Yazzie, center, speaks to a group of sixth and 12th graders about her case on Tuesday in Gallup.

GALLUP – Six years have elapsed since the historic Yazzie/Martinez v. State of New Mexico ruling, but significant disparities in educational outcomes for low-income, Native American, disabled students, and English language learners remain a pressing concern. Although the state has increased education funding by a staggering $1.6 billion since 2019, proficiency rates for these vulnerable student groups continue to lag the statewide average by as much as 30 percentage points, indicating that financial investment alone is insufficient without meaningful systemic changes.

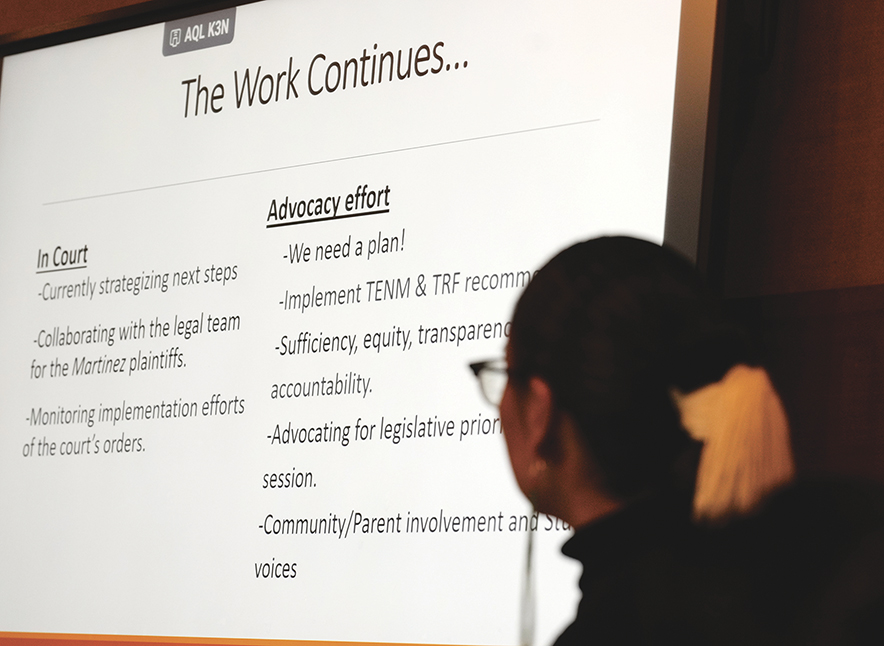

Special to the Times | Donovan Quintero

Wilhelmina Yazzie looks at the screen while talking about the Yazzie/Martinez v. State of New Mexico case on Tuesday in Gallup.

Wilhelmina Yazzie, a central figure in the advocacy for educational equity, recently spoke out about the persistent inequities during an event in Gallup.

“We’ve seen some progress, like teacher raises, which are certainly beneficial,” she stated. “And we’ve also included our history in the social studies curriculum here in New Mexico.”

Despite acknowledging these positive developments, Yazzie added that many fundamental issues outlined in the Yazzie/Martinez case remain unaddressed.

The Yazzie/Martinez ruling, delivered in a comprehensive decision by the late Judge Sarah Singleton, outlined essential requirements to support at-risk students. The ruling emphasized the necessity for resources ranging from transportation and social services to academic support and counseling. Yazzie recalled the challenges raised during the COVID-19 pandemic when she and her colleagues filed a motion highlighting the lack of internet access, laptops, and tablets for children in rural areas and tribal schools. This action ultimately led to the state providing crucial additional resources.

Central to the Yazzie/Martinez case are four specific student groups: Native American children, English language learners, students with disabilities, and low-income students. Yazzie expressed frustration at the slow pace of progress in meeting their needs, emphasizing the urgency for a well-defined plan from the state.

“We’ve been waiting for the state to provide a plan on what they’re doing, what has happened, and what they’re going to do,” she lamented.

Despite the influx of funding aimed at addressing educational disparities, Yazzie noted that the needs of at-risk groups continue to be inadequately met. Reports from within the special education sector reveal ongoing issues, with many students still feeling marginalized and unsupported.

“I’m hearing a lot from special education that they’re still suffering. They’re still not included. They’re still being pushed away,” she said, highlighting the systemic failures that persist within the education system.

Substantial change

In September, the New Mexico Center on Law and Poverty filed a motion urging the court to compel the state to comply with the 2018 ruling. This joint non-compliance motion, submitted by both parties, asserts that the state has not fulfilled its obligations under the court order.

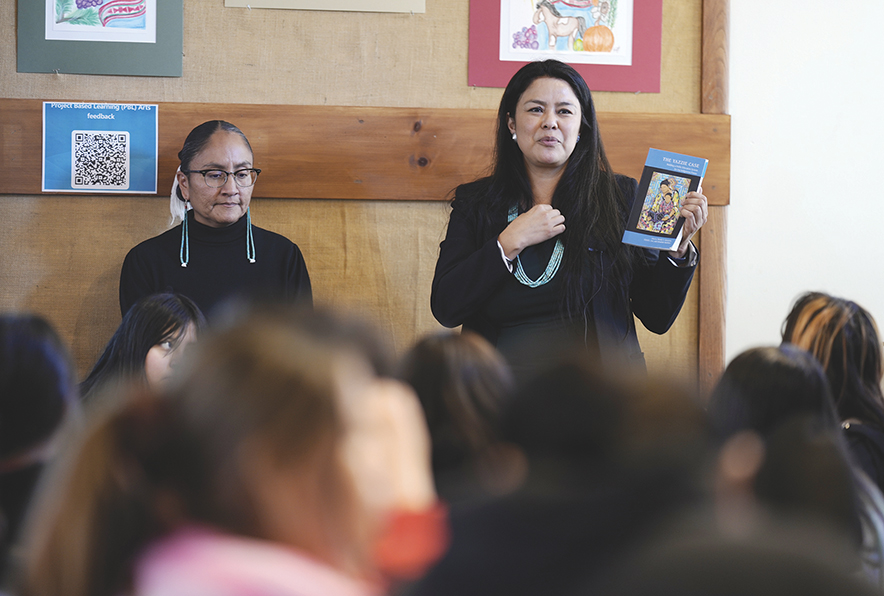

Special to the Times | Donovan Quintero

Dr. Wendy Greyeyes, right, holds a book titled “The Yazzie Case,” while talking about the Yazzie/Martinez v. State of New Mexico case to a group of sixth and 12th graders on Tuesday in Gallup.

“This motion requests a remedial action plan that includes nine key components designed to rectify ongoing deficiencies,” Yazzie explained.

As the state approaches a deadline of Nov. 21 to respond to the motion, Yazzie remains cautiously optimistic yet skeptical about the likelihood of substantial change.

“I think we pretty much know what the response is going to be—that we’ve done what we need to do,” she remarked, expressing concern that the state may downplay the urgency of the situation.

The Yazzie/Martinez case, originally filed in 2014 by a coalition of parents, students, and school districts, highlighted long-standing violations of the New Mexico Constitution’s guarantee of a sufficient public education. The landmark ruling seven years later brought national attention to the systemic inequities entrenched in the state’s educational framework. Advocates like Yazzie continue to fight for the rights and needs of New Mexico’s most vulnerable students, stressing the critical importance of accountability and effective action in the wake of the court’s mandate.

Six years have elapsed since the historic Yazzie/Martinez v. State of New Mexico ruling, but significant disparities in educational outcomes for low-income, Native American, disabled students, and English language learners remain a pressing concern.

Struggle for educational equity

Although the state has increased education funding by a staggering $1.6 billion since 2019, proficiency rates for these vulnerable student groups continue to lag the statewide average by as much as 30 percentage points, indicating that financial investment alone is insufficient without meaningful systemic changes.

A critical player in this struggle for educational equity is the Gallup McKinley County School District, or GMCS, which employs a staff of 1,819 individuals, including 778 teachers tasked with creating an optimal learning environment for the 10,109 students enrolled across its 33 schools.

GMCS serves a diverse student body where nearly 80% identify as Native American, reflecting the diverse cultural heritage of the county, which includes the Navajo Nation and Zuni Pueblo. The district also faces unique challenges with a significant population of English Language learners — 3,356 students or 30% — and a notable percentage of homeless students — 259 students or 2%.

As the geographically largest school district in New Mexico, covering 4,857 square miles, GMCS confronts logistical challenges in delivering resources and support to students spread across a vast and diverse landscape.

The Navajo Nation encompasses parts of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, where 17 school districts operate a total of 244 schools serving approximately 38,109 Navajo students. Of these, about 23,056 students—around 60.5%—attend public schools located within the Nation’s borders, highlighting both the vital role and the challenges these schools face in delivering quality education.

Educational disparities

In addition to public schools within the Navajo Nation, another 48,172 Navajo students attend public schools outside its boundaries, further complicating efforts to address educational disparities. The Bureau of Indian Education, or BIE, plays a significant role in this landscape, with 66 out of 183 BIE-funded schools and residential halls situated in the Navajo Nation. Of these, 32 are BIE-operated schools, while one follows a Public Law 93-638 contract, and 33 are tribally controlled grant schools under Public Law 100-297.

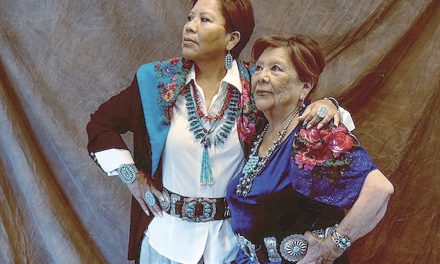

Special to the Times | Donovan Quintero

Wilhelmina Yazzie speaks about her Yazzie/Martinez v. State of New Mexico case on Tuesday in Gallup.

Collectively, BIE-operated and tribally controlled grant/contract schools educate approximately 39.5% of all Navajo students, underscoring the importance of these institutions in providing access to education for Indigenous youth. Yet, as funding increases come with the promise of improving educational outcomes, the struggle for equity continues to demand attention and action from policymakers and educators alike.

According to a report conducted by the New Mexico Public Education Department, titled “Tribal Education Status Report 2019-2020,” found in a three-year statewide assessment comparison of percent proficiencies by ethnicity in reading, math, and science in the school year 2018-19, 25 percent of Native American students were proficient in reading, 12 percent in math, and 20 percent in science. The proficiency rate of Native American students in 2018-2019 decreased from the school year 2017-2018 in reading by four percent, remained the same in math, and decreased slightly by one percent in science. Overall, the report concluded that Native American students ranked lower than Caucasian, African American, Asian, and Hispanic students.

This compliance report provides information regarding American Indian students’ public school performance and how performance is measured. This information is shared with legislators, educators, tribes, and communities and is disseminated at the semiannual government-to-government meetings.

The New Mexico Public Education Department, or NMPED, is required by statute to provide this compliance report annually so that education and tribal communities can make informed decisions about how to meet the academic and cultural needs of Native American students and improve outcomes. Indian education stakeholders and other education institutions may use the data in this report for local planning and improvement processes focused on improving the quality of education for Native students.

The data in this report was gathered from the 23 school districts and seven charters that serve a significant population of Native students or have tribal lands located within their school boundaries. The data collected includes student achievement, attendance, school district initiatives, and dropout and graduation rates. Of the 23 school districts, 22 submitted a districtwide Tribal Education Status Report that supports the following sections: school safety, parent and community involvement, and education programs targeting tribal students that incorporated Indigenous research, evaluation, and curricula.

While she continues to see persistent inequities within GMCS, Yazzie spoke about some progress being made.

“We’ve seen some progress, like teacher raises, which are crucial,” she noted, emphasizing that true equity requires not just financial investments but also targeted strategies addressing the specific barriers faced by the district’s marginalized populations.

Sixth-grade through 12th-grade students from Six Directions, a charter school that was established in 2015, told the students her story began similarly to theirs.

“I grew up on the reservation with no running water, no electricity. I grew up in a hogan — although in the Western view, they think that’s poverty. They think that’s poor, but really, in reality, in our own culture, we learned to live off the land, we learned our language, we learned our culture, we learned a lot of that,” said Yazzie. “That’s how I was brought up. We’re still fighting for all of you.”

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow