Tribe, retired advocate opposed to Diné’s execution

WINDOW ROCK

The Navajo Nation expressed opposition to the death penalty in a case involving a Navajo tribal member.

In a letter dated June 6, 2021, Navajo Nation Attorney General Doreen McPaul asked Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich to respect Navajo traditional beliefs about taking a human life.

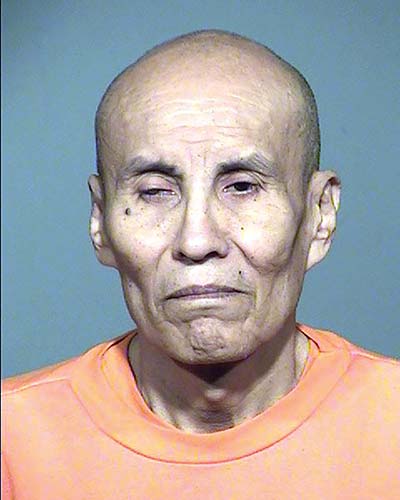

Courtesy of Arizona Department of Corrections

Clarence Dixon

In the letter about Clarence Dixon, 66, originally from Fort Defiance, who was convicted and sentenced to death for a 1978 sexual assault and murder of an Arizona State University student, McPaul said to Brnovich that the tribe opposed the scheduled May 11 execution. This is because executions are against traditional beliefs.

“Navajo culture and religion holds every life sacred and instructs against the taking of human life for punishment,” the tribe’s attorney general said. “Committing a crime not only disrupts the harmony of the community. The death penalty removes the possibility of restoring harmony whereas a life sentence holds the opportunity to reestablish harmony and find balance in our world.”

Attorneys representing Dixon have also been arguing his eighth amendment right – which states, “Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted” – was being violated.

According to motions filed in Arizona court, Dixon has been declared mentally incompetent, his attorneys argued.

An April 28 petition asking the Arizona Board of Executive Clemency and Gov. Doug Ducey to commute Dixon’s death sentence was filed to protect his right to appeal for clemency.

An April 8 lawsuit filed against the clemency board and Ducey was rejected on April 19 by the Maricopa County Superior Court, citing, “law enforcement is not a profession.”

In the lawsuit, Dixon’s attorneys said the clemency board is comprised of four board members, all of whom are retired law enforcement officers.

Joshua Spears, one of Dixon’s attorneys, said Dixon was entitled to a fair clemency hearing before an impartial clemency board, “not one that is illegally stacked with law enforcement officials.”

“We are reviewing our options to appeal the Superior Court’s ruling,” Spears said on April 19.

Severe mental illness

According to his attorneys, Dixon has a severe mental illness and is legally blind. He was declared mentally incompetent in 1977, and assault charges against him were dropped.

“His case presents many important factors relevant to a clemency determination,” Spears said.

Dixon is scheduled to be the first person executed in Arizona in eight years.

Lenny Foster, who retired after 37 years of working with state and federal Navajo and Native American inmates, said he became acquainted with Dixon in 1988 at Perryville State Prison in Goodyear, Arizona.

Foster was working as a spiritual advisor and was director of the Navajo Corrections Project. The project was created in 1983 and provided Native American state, federal, and tribal inmates access to traditional religious practices.

Foster said Dixon participated in sweat lodge ceremonies at the time and that is how he became acquainted with him.

Foster said he was aware of Dixon’s scheduled execution date.

“I’ve been talking to him on the telephone, providing him with spiritual support,” Foster said.

After their 45-minute conversation, Foster said a prayer for him. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, he said he could not do a sweat lodge ceremony for him in person.

He added he would provide Dixon with spiritual counseling one last time on May 10.

Foster said he opposed the death penalty because it went against Navajo traditional beliefs.

“Our teachings have taught us not to take life and have been passed down to us by our grandmothers and grandfathers,” Foster said on Tuesday. “Taking the life of another person is taboo. I consider myself to be traditional and to not take life indiscriminately.”

Foster said the Navajo Nation was a true believer in traditional values and beliefs about life and that it honored all life on Mother Earth “since time immemorial.”

Fundamental law

The tribal government based its laws on Navajo fundamental law, or Diné Bi Bee Nahaz’áanii, which embodies four Navajo cultural beliefs: Diyin bits’ą́ą́dę́ę́ bee nahaz’áanii, Diyin Dine’é’ bits’ą́ą́dę́ę́ bee nahaz’áanii, Nahasdzáán dóó Yádiłhił bits’ą́ą́dę́ę́ bee nahaz’áanii, and Diyin Nihookáá’ Diné bi bee nahaz’áanii.

The laws “provide sanctuary for the Diné life and culture,” the Diné Bi Bee Nahaz’áanii law states.

Under Diyin Dine’é’ bits’ą́ą́dę́ę́ bee nahaz’áanii, or Customary Law, states, “It is the right and freedom of the people that every child and every elder be respected, honored and protected with a healthy physical and mental environment, free from all abuse.”

“On behalf of the Navajo Nation with respect to capital punishment, explains our position on Dixon’s case, an enrolled member of the Navajo Nation,” McPaul’s June 21, 2021, letter to Brnovich read. “For these reasons, the Navajo Nation submits its strong opposition to the execution of a Navajo tribal member by the state.”

Reginald Turner, president of the American Bar Association, also wrote a letter to the Arizona Board of Executive Clemency, stating, “the ABA did not believe that justice would be served by Dixon’s execution, who has been struggling with a ‘serious and longstanding mental illness.’

“As a result, we urge the board to recommend clemency for Mr. Dixon, allowing Gov. Ducey to consider whether Mr. Dixon’s case should proceed to execution,” Turner’s April 13 letter said.

According to Turner, the U.S. Supreme Court describes clemency as a “fail-safe in our criminal justice system.”

“In Arizona, the clemency power rests with the governor,” Turner wrote.

But for Ducey to consider clemency, the clemency board had to recommend it first.

“As a result, this board’s consideration of clemency is vital to ensuring that the governor is able to act as this critical fail-safe,” he said.

Dixon’s attorneys state he developed schizophrenia at 21, which was never treated for his mental illness while in prison.

They added Dixon became an alcoholic and drug addict at a young age and had to walk several miles to a hospital to get open-heart surgery.

Since being incarcerated, Dixon’s mental health has continued to deteriorate.

Foster: Abolish death penalty

Foster said he hopes the Arizona Legislature will eliminate the death penalty for Foster.

“I would like to see it abolished,” he said. “He’s (Dixon) been on death row for 18, 19 years. It has to be a very hard psychological struggle for him.”

Foster said he’s served over 2,000 young Native American men and women before retiring in 2018 and has visited 96 state and federal prisons.

“The death penalty is very emotional and serious,” he said. “The state is taking a person’s life. It has to be taken seriously. He’s facing the death penalty. I do not take it lightly.”

Correction: May 8, 2022

An earlier version of this article misstated the name of the prison where Lenny Foster became acquainted with Dixon. The name of the prison is Perryville State Prison, not Dixon State Prison.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow