Weavers’ hands: Adopt-A-Native Elder Navajo Rug Show supporting Diné weavers for 40 years

Navajo Times | Kianna Joe

A pair view a yé’ii rug displayed during the annual Navajo Rug Show and Sale in Scottsdale, Ariz., on Feb. 17. The event took place at the Holland Community Center Feb. 16-18.

SCOTTSDALE, Ariz. – Lynda Myers, the founder of Adopt-A-Native-Elder, teared up remembering a visit to a Názlíní grandmother who told Myers with shaky hands that she couldn’t weave anymore.

Myers had been selling that grandmother’s rugs for years and remembers holding the hands that spent hours on the loom.

“I had helped her sell many rugs,” said Myers. “I was watching the tears go down her face as she saw all the weavers selling their rugs and I thought, ‘This is painful.’ That’s the hardest part, when they say, ‘Stop giving me yarn.’”

At the Holland Community Center in north Scottsdale, from Feb. 16-18, countless rugs hung on walls and tables as visitors walked around admiring and possibly buying works of art from Diné elders through ANE.

Helping Diné elders

ANE is an organization that aims to help Diné elders in the Navajo Nation by delivering food, medical supplies, firewood, and other supplies elders might need.

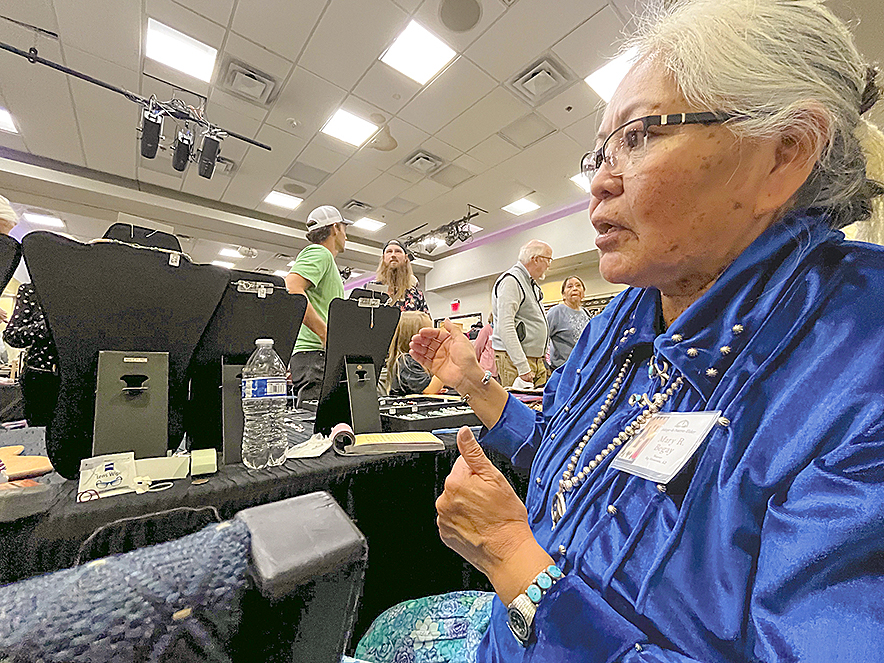

Navajo Times | Kianna Joe

Mary R. Begay from Big Mountain, Ariz., vends at the annual Navajo Rug Show and Sale in Scottsdale, Ariz., on Feb. 17. The event took place at the Holland Community Center Feb. 16-18.

According to the ANE website, the organization has helped over 800 elders since the 1990s.

Since then, Myers had been behind organizing a rug show and sale in Deer Valley, Utah, with 20-30 sellers until COVID-19 happened.

“During that time, I lost a lot of weavers,” said Myers. “They were all old grandmas.”

Myers knew she wanted to continue having the rug show and sale to help the families she had gotten to know for 30 years.

When Myers went to the former location for the rug show, it was under new management. They sought $30,000 to host the rug show.

However, a Scottsdale couple that bought a rug years before contacted Myers to help. After several phone calls, the Holland Community Center in Scottsdale became the new home for the rug show and sale.

“This is our second year here, and last year we did really well,” said Myers. “We’re representing 70 weavers right now.”

All proceeds go back to the elders behind the rugs, and grants pay for the bundles of wool provided by ANE.

“One of our big goals has been to see it (weaving) passed on, and (I’ve) been out here for 40 years with the elders,” said Myers. “And to see it passed on and see their (elders) children pick it up, and most of these weavers are grandmothers themselves representing their mothers and grandmothers who were a part of the initial program, is just amazing. It’s a full circle.”

Selling rugs

Myers didn’t start ANE to sell or show rugs. She saw how important it was for many elders and knew it was necessary, like everything else ANE helps with.

When Myers began ANE to help supply food, she remembered distributing food in the Big Mountain, the Dził Nitsaa area. It was there an older woman approached Myers and asked her if she could sell her rug.

“At the time, I was an artist, and I was like, ‘Well, you know I could try,’” said Myers. “I take it back and sell it and send her the money.”

Navajo Times | Kianna Joe

Photographs of Diné elders and their sheep surround a rug on display at the annual Navajo Rug Show and Sale in Scottsdale, Ariz., on Feb. 17.

The following food run Myers did, the same older woman showed up again but with two rugs and asked Myers the same thing.

Myers went out, sold the rugs, and sent back the money. The third time Myers returned to distribute food, the older woman had her three sisters with her, each with two rugs.

“All of a sudden, I know nothing about rugs, but now I’m learning everything about rugs,” said Myers. “I’m selling these rugs, and then the next time I come back on the food run, all these ladies have rugs that I need to sell.”

Myers had been taking pictures of the rugs and sending them to museums, art exhibits, friends, and anywhere so she could get them sold.

Later, Myers brought the weavers and their rugs to an art gallery in Park City, Utah, allowing them to set up and sell them for four hours.

The following year, they allowed six hours, and from then on, Myers remembered all the older women, and the másáni, getting together, making food, and preparing to sell each year.

Buying necessities

Before Myers met the elderly weaver, she had watched the screening of “Broken Rainbow,” a documentary on the Navajo-Hopi relocation.

“It disturbed me. It bothered me so much what was going on,” said Myers.

Myers had met a woman who brought weavers, and now knowing what was going on with Diné, Myers told that woman she would create an art piece. It sold, and Myers would give her the money from it.

After Myers’ art piece sold, Myers took the woman out to get groceries per her request.

“She asked me, ‘Why are you doing this?’ and I told her I needed to. I couldn’t watch what was happening,” said Myers.

Later on, the woman returned to Myers’ home. She told Myers how she got lost on the dirt roads at Big Mountain and came across an older woman whose vehicle broke down. That woman and other elders she cared for had been without food for three days.

The woman gave the food and water Myers had just bought her to the woman.

After visiting the Navajo Nation in person and seeing the condition many elders lived in, Myers continued to make trips back to the Navajo Nation to drop off food. That’s where ANE began.

Weavers at the show

One of the 70 weavers represented at the show was Mary Begay.

Begay is Tábąąhá born for Naakaii Dine’é. Her maternal grandfather is Tł’ááshchí’i, and her paternal grandfather is Tsédeeshgizhnii. She is from Dził Nitsaa.

Begay became a part of the rug show through her mother, who had been a part of ANE when it first started.

“When our community lost more than half of its land base to the Hopi tribe, Lynda Myers came, and she started to help the people in our community,” said Begay. “And first it was food, then it was other necessities, and then a rug show. My mom got involved, and she needed a driver, so I started to drive her there.”

Begay remembered herself and her sisters watching her mother weave since she was young.

Begay’s mother expected to watch her weave and do the same thing.

“She didn’t take our hands and say, ‘Here, do this.’ It was more of, ‘Watch me and you’ll learn it,’” said Begay.

Now, Begay, her sisters, daughter, and nieces know how to weave after learning from Begay’s mother.

Having started with 10 rugs, Begay was down to two. The money she earns goes back to helping her family and her elderly father, who is a part of the ANE program.

As Myers hustled and bustled around, ensuring her Diné friends and family had everything they needed, elders stopped her and introduced her to their kids and new grandbabies.

After 40 hard years of driving back and forth from the Nation, taking in the sharp Navajo woman glares and cold shoulders, Myers can now meet the newest members of the families she’s helped.

“To touch some of the weavers’ hands, the elderly’s hands, some of them were over 100 years old, it is just beautiful,” said Myers.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow