Guest Column: Clean up abandoned mines, milling sites once and for all

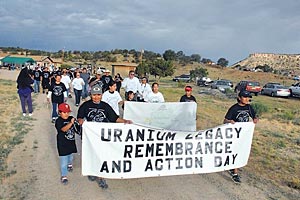

The 32nd anniversary of the Church Rock uranium tailings spill was observed July 16 with an awareness march starting from the home of Teddy Nez to the site of the uranium tailings spill in Church Rock, N.M. July 2011

By U.S. Senator Martin Heinrich

Special to the Times

For far too long, Indian Country has been left to fend for itself in dealing with the legacy of hardrock mining. Too many tribal communities, including many on the Navajo Nation, live among abandoned mining and milling sites that contaminate their water, air, and food.

In August, a large plume of bright orange toxic waste spilled from the abandoned Gold King Mine in Southwest Colorado into the Animas and San Juan Rivers and polluted the Four Corners region, including the Navajo Nation. The spill served as yet another wake-up call to finally fix our nation’s policies on abandoned mines and hardrock mining.

The General Mining Act of 1872 came along in an era of unrestrained western expansion. It allowed individuals and companies to claim ownership of minerals in the public domain — such as gold, silver, copper, uranium, molybdenum, and others — simply by locating a mineral source, staking a claim, and paying $5 an acre for the land. Miners did not have to consider environmental impacts or make any plans to clean up the waste they left behind, which has created the pollution and contamination we confront today.

This law drew thousands of people to the West — my father and my mother’s father both made their living working in hardrock mines. Hardrock mines provided the raw materials to build this country, and during the Cold War, uranium from the Navajo Nation was transformed into nuclear weapons to defend our nation.

But shortsighted policy left behind a scarred legacy on our lands. There are estimates that 40 percent of Western watersheds have been polluted by toxic mining waste and that reclaiming and cleaning up abandoned mines could cost upwards of $32 to $72 billion. Unlike other 19th century western settlement laws, which have long since been reformed or replaced, the Mining Act of 1872 is still on the books. While developers of resources like oil, natural gas, and coal pay royalties to return fair value to taxpayers for our public resources, hardrock mining companies can still mine publicly-owned minerals for free. And we still don’t have a plan to address a century of pollution from abandoned mines.

We need to bring our mining laws into the 21st century. That is why I introduced legislation with Senator Tom Udall and Congressman Ben Ray Luján to require that reasonable royalties and fees from hardrock mining be used to create a dedicated funding stream for cleaning up toxic mine waste. A reclamation program will allow states, tribes, and non-profit organizations to collaborate on projects to restore fish and wildlife habitat affected by past hardrock mining.

We also need to reform the permitting process for new mines. Under our legislation, operators will need to protect water and wildlife resources and provide financial assurance that they can fund reclamation and restoration efforts after their mines close.

Another component of reform that I support is updating the Clean Water Act to allow Good Samaritan organizations — groups willing to conduct mine reclamation and habitat restoration projects — to help Western communities clean up abandoned mines without assuming financial and environmental liability for sites that they did not contaminate.

The Gold King spill was not the first or the worst major hardrock mining spill to affect the Navajo Nation. In 1979, a breached dam at a uranium mill tailings disposal pond near Church Rock, N.M., on the Navajo Nation, sent more than 1,000 tons of solid radioactive waste and 93 million gallons of acidic liquid into the Rio Puerco.

The Navajo Nation has more than 500 abandoned uranium mines. In October, I visited a large uranium tailings pile in Shiprock, and an abandoned uranium mine in the Northern Navajo Nation. I met with officials at the Navajo Abandoned Mine Lands Reclamation and Uranium Mill Tailings Remedial Action office and learned about their efforts to clean up hundreds of sites after decades of mining.

After the Gold King spill, when I toured affected communities, I visited with impacted residents and met with President Russell Begaye in Window Rock, to discuss the impacts of the disaster on the Navajo Nation. Navajo officials did not receive timely notification from the EPA that the spill had occurred. Because water intake from the San Juan River had to cease, water had to be delivered to homes and for agriculture and livestock purposes. Unfortunately, problems related to water delivery caused further concern to farmers and ranchers.

I share the anger and frustration over this terrible accident and have demanded that the EPA act with urgency to protect the health and safety of our communities and repair the damage inflicted by the spill on the watershed. This must be our top priority. New Mexicans and citizens of the Navajo Nation can count on me to conduct aggressive oversight as this work is completed.

But we must also look over the horizon and take action to reform outdated policy to clean up the hundreds of thousands of similarly contaminated mines across the West and Indian Country that are leaking toxins into our watersheds.

We shouldn’t wait for more disasters to strike. Western communities, including tribal communities, deserve full and complete protection of their water, land, and livelihoods. Our nation owes it to these communities to clean up these sites once and for all.

To read the full article, pick up your copy of the Navajo Times at your nearest newsstand Thursday mornings!

Are you a digital subscriber? Read the most recent three weeks of stories by logging in to your online account.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow