50 Years Ago: Chairman, council feud continues

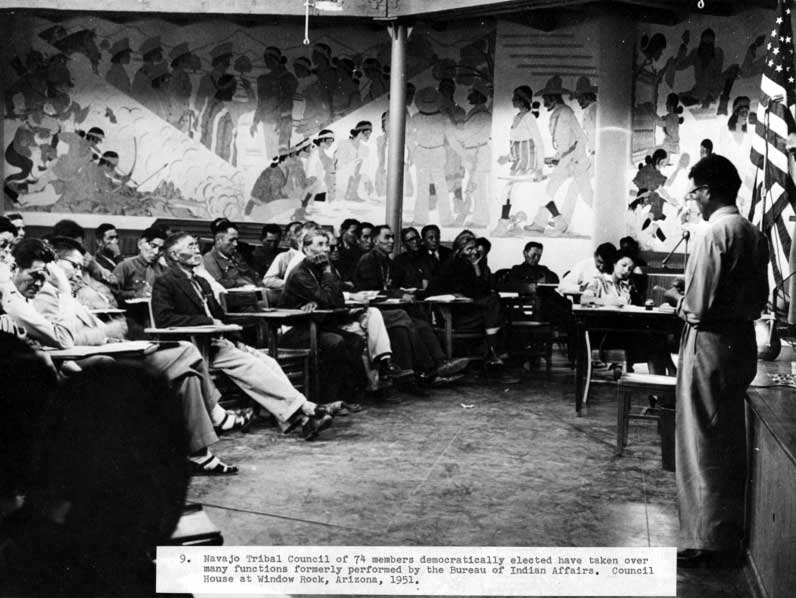

The Navajo Tribal Council originally consisted of 74 elected members who took over duties that had been performed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. (Photo of Council in 1951 courtesy of Truman Library.)

As 1964 ended, the one thing that most tribal members could agree on was that the Navajo tribal government was in a crisis mode and 1965 did not promise to be any different.

The Navajo Tribal Council originally consisted of 74 elected members who took over duties that had been performed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. (Photo of Council in 1951 courtesy of Truman Library.)

The main problem centered around the fact that the chairman did not get along with most of the members of the Navajo Tribal Council who were still upset that he had defeated the former chairman, Paul Jones, and wanted to make changes in the way the tribal government responded to the needs of the Navajo people.

Throughout 1963 and 1964, the Jones supporters on the council — which were termed the “Old Guard” by the Navajo Times — kept rejecting any proposal by the Nakai administration that would change or dilute any programs that had been created by Jones.

As for new programs being pushed by Nakai, forget about it. The council was in no mood for government reform.

The Old Guard had the support of the tribe’s general counsel, Norman Littell, who spent most of 1964 in a bitter fight with Nakai in order to keep his job. Those fights included lawsuits, threats of lawsuits and a massive public relations campaign that was fought in the Navajo Times, the border town newspapers and even the Albuquerque Journal.

Unfortunately for Nakai, Littell won every one of those battles even though Nakai was able to get the Interior Department on his side.

Nakai himself found himself stripped of most of his powers by the council as 1964 ended because of an audit that showed massive problems within the tribal government because many departments were ignoring the tribe’s financial laws and were approving items without getting the proper authorization.

The blame for this rested on Nakai, who admittedly had spent most of 1964 carrying out the agenda he had outlined in his campaign to be chairman and therefore, did not spend much time overseeing the operation of the tribal government.

He told the Navajo Times that he left the day-to-day operations of the tribe to Maurice McCabe, the tribe’s executive administrator, a position that doesn’t exist in the tribal government any longer. Nakai and McCabe did not get along but McCabe was considered safe in his job because he had the support of the Old Guard on the council.

He claimed, according to news accounts from that time, that his efforts to do something about the tribe’s financial problems were stymied by Nakai who admittedly wanted him gone but couldn’t do so because of his support in the council.

Much of the problems the tribe were facing in that day stemmed from favoritism in hiring — it was more important who you knew rather than whether or not you were qualified to handle the job. Another problem was the BIA — it was supposed to oversee tribal financial operations as well during those days but the people in charge of doing that for the BIA were, in some ways, just as clueless about how to perform their jobs as many tribal department directors were.

As 1965 began, McCabe had been given more power that the chairman since he now oversaw personnel actions as well as anything to do with tribal finances and he pledged to use whatever resources were available to him — including firing unqualified people, if necessary — to get the job done in the first half of the year.

But while Nakai was having problems, another person within the tribal government, was enjoying a good year and that was Peter MacDonald.

He had been convinced to leave his job in California the year before and move his family — wife, Ruby, and two children, Peter, Jr. (Rocky) and Linda — to Window Rock and help him in his efforts to make changes in the way the tribal government operated.

MacDonald would become the go-to guy in the Nakai administration and in 1964 one would hear more about what he was doing than what Nakai was doing.

Part of this was because of Nakai’s distrust of the news media. He felt the news media was out to make him look as if he couldn’t handle the job — after all, he was a former disc jockey at a radio station in Flagstaff before being elected and had little experience in running a government or business the size of the Navajo Nation.

What Nakai liked was MacDonald’s ability to portray the right amount of professionalism in working with the press, something that he couldn’t do. In fact, the few times he did talk to the press while in office, he would later say he was misquoted or that the reporter never understood what he was trying to get across.

In fact, anyone reading the Navajo Times in 1964 would probably come to the conclusion that MacDonald was being groomed to be a future leader of the tribe and that one day he would become a candidate for tribal chairman — but not until Nakai was ready to leave office.

As for MacDonald, reporters probably felt it was easier to go to him for information rather than trying to see Nakai and get the usual government run around.

As 1965 approached, MacDonald was ready to take on his biggest challenge to date — heading the newly created Office of Navajo Economic Opportunity — and using this as a springboard to challenging Nakai for the leadership of the tribe five years later.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow