50 Years Ago: Ft. Defiance played a role in Diné history

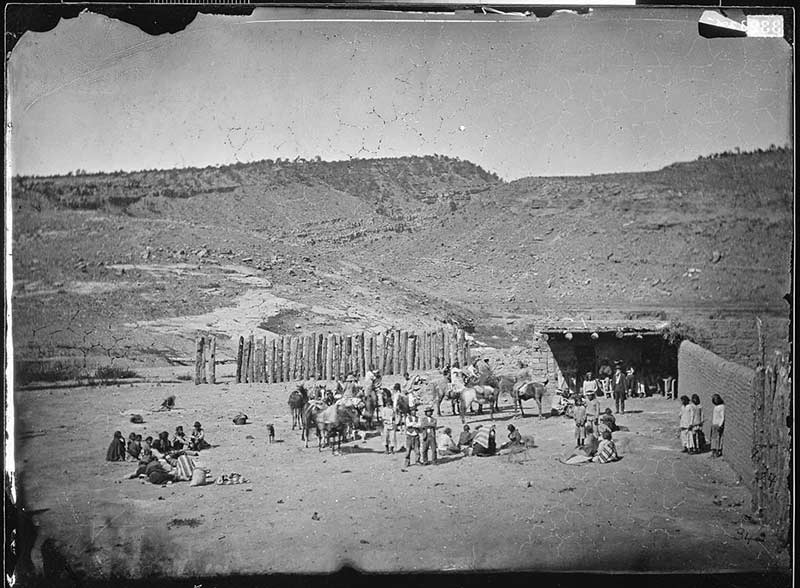

Fort Defiance as it existed in 1873. Source: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration via Wikimedia Commons.

As the Navajo Times prepared to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Long Walk in June, the paper gave its readers a front page story on the historical importance of Fort Defiance to the history of the Navajo people.

Fort Defiance was the site of the first day school on the reservation in 1869, the first mission in 1871, the first boarding school in 1883, the first hospital in 1897 and the first public school in 1954.

It began as an actual fort that was the site of a battle in April 1861 when soldiers withstood an attack by the Navajos, according to the Navajo Times. It was abandoned a short time later and was renamed Ft. Candy when it became the headquarters for Lt. Col. Kit Carson in his quest to round up as many Navajos as he could to take them to captivity at Ft. Sumner.

In 1863 and 1864, he and a volunteer troop of soldiers lived in Fort Defiance, where they planned a campaign to make the reservation unlivable to the Navajo people by destroying their hogans and crops and killing off any sheep they could find.

The Long Walk began at Fort Defiance and in 1868, when the Navajos were allowed to return, it became the site of the first Indian agency.

The Navajo Times reported that the people of Fort Defiance in 1968 were planning to provide residents of the chapter history lessons in June as part of the chapter’s celebration of the anniversary.

The paper also reported that anyone who wanted to know more about the history of the Fort Defiance area should make plans to purchase a new book by Maurice Frank entitled “Fort Defiance and the Navajos.” It was to go on sale June 1.

In other news, John McPhee died on May 27 at the age of 63 of a heart attack.

He had lived on the reservation for 15 years and had a lot of influence during the late 50s and early 1960s with the chairman at that time, Paul Jones. One of his main efforts was the creation of a tribal newspaper which he said would not only provide reservation residents with news about what their government was doing but would also promote reading among the younger Navajos.

It was because of his efforts that the tribe formed a committee to look into it. The committee agreed it was a good idea and sent a delegate in the late 1950s to San Francisco to convince Marshall Tome, who was working for a newspaper there, to come back to the reservation and oversee its startup.

McPhee was known for his organizational abilities and was an administrative assistant to Jones. He was the go-guy if anyone wanted a new program or to get something off the ground, which was why he became involved in the development of the Navajo Times.

But it wasn’t only the Times that he had a part in creating. During his time on the reservation, he was responsible for helping create the Navajo police department, the tribal park system, the Navajo Tribal Museum, the annual tribal fair and a reservation-wide radio broadcast.

You could say that whatever Jones wanted accomplished during his time in office, McPhee had a hand in it.

After Jones was defeated by Raymond Nakai in 1962, McPhee left the reservation and moved to Telluride, Colorado, where he started his own newspaper. But his family said he couldn’t forget the reservation and the life he had there. At the time of his death he was working on a book about the Navajos.

Final discussions were going on this week to get Mrs. Old Man Mud’s wife and her twin sister, Mrs. Crookedneck, to Window Rock for one day to participate in the 100th anniversary celebration.

Evidently, talks had been going on with the family for several weeks because of concerns as to whether the 104-year-old sisters would be able to make the journey from Tuba City to Window Rock.

Despite their age, both sisters were still active and one reportedly still herded sheep.

But Wilsie Bitsie, speaking for the family, said the trip from Tuba City would be very hard on the two sisters, given the condition of the road and the fact that it would take several hours.

But since they were the only ones alive who had been at Fort Summer during the years of Navajo captivity, their presence would mean a lot to those who took part in the celebration.

He said both sisters were looking forward to being a part of the celebration but he wanted to be sure that the tribe did everything it could for their comfort and well-being during the time they were in Window Rock.

Dick Hardwick, editor of the Navajo Times, said every effort was being made to get them here because, if they do attend, it will be “quite an attraction.”

One of the things people wanted to ask them was how much they remembered of living at Fort Sumner. Although they were just three and four years old at the time, people were hoping that they had some memory of what happened.

From the time of the articles written during that period, there was apparently little in the way of recorded memories of those who were still alive in the 50s and 60s when there were ways available to record their memories.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow