50 Years Ago: Grassroots work to make Crownpoint a chapter

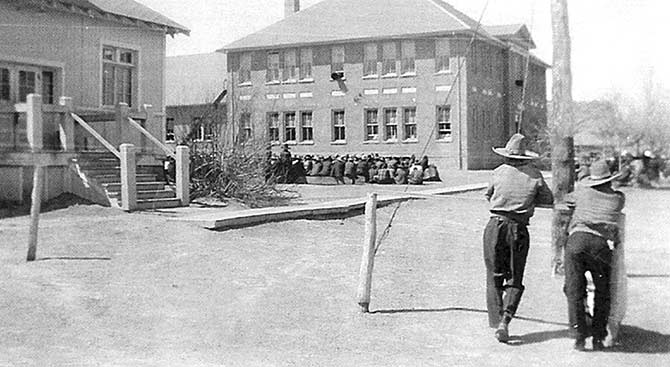

(Courtesy photo - Crownpoint Historical and Cultural Heritage Council) A meeting is held in the 1920s at the Pueblo Bonito Agency Boarding School in Crownpoint. The kindergarten building (later town hall) is on the left.

People in Crownpoint Chapter may not remember this, but 50 years ago they didn’t exist.

Yes, in all the years that the Navajo government operated, there was no chapter in Crownpoint, a community that in 2014 continues to be the center of activity in the Eastern Navajo Agency and the gateway to such attractions as Chaco Canyon.

As one newspaper article in 1964 pointed out, the lack of recognition by the tribal government meant, “Crownpoint has not gotten the benefits from the tribe as some communities of comparable size have received.”

But a number of residents were working behind the scenes in September 1964 to correct this problem and a resolution was going through the committees of the Council to make Crownpoint a chapter.

If the Crownpoint Chapter is approved by the Council, it will be the 97th chapter organization on Navajo land, said the Navajo Times.

The Times pointed out that Crownpoint would have been named a chapter a long time before but for one small problem — it was in the Checkerboard area and some on the Council felt that a chapter had to be, well, completely on Navajo land.

But this hasn’t stopped people in the community from meeting and acting like a Navajo chapter. They even elected their own pre-chapter officials in September — Jack Martin as president, Lincoln Perry as vice president, Abe Plummer as secretary and Jackson Perry as treasurer.

Martin said that other chapters have gotten named because a grassroots organization was formed and if other organizations were able to do it, the people in Crownpoint would be able to do it.

The movement to name Crownpoint as a chapter is at the same time another movement is gaining support on the reservation — one that would expand the current 77-member tribal Council.

As more communities on the Navajo Reservation began demanding to be recognized and the workload of the Council continued to expand, the movement to increase the size of the Council seems to have a life of its own.

There were those who wanted to increase it to 96 members, one delegate for each chapter, but the bigger chapters, like Tuba City, Chinle and Shiprock — all of who had more than one representative on the Council — oppose this.

Then there was another group that wanted to double the Council’s size to about 140 members but this was rejected by almost everyone in the Council for logistic reasons — there was no way that 140 desks could be put in the Council Chambers without tearing down some walls or expanding its size, something that no one really wanted to do.

One architect speculated that you could probably get about 90 desks in the building and still have room for chairs for spectators around the room.

Of course, one could make the desks smaller or get rid of them altogether, having Council delegates sit in pews, which would allow for double or more delegates.

As this was being debated, Peter MacDonald was taking steps that would eventually lead to his total domination over all aspects of life on the reservation in the next decade.

No one quite knew what would happen if he was successful in getting the federal government to agree to provide the reservation with poverty funds to help out low-income Navajos, of which there were many in 1964.

Apparently, not everyone was happy about the Navajos seeking $1.5 million in poverty money because of reports that the tribe was wealthy because of oil and coal royalties.

This even forced Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall to give out a statement supporting the tribe’s request for $1.5 million.

He said in a news conference that estimates that the Navajo Tribe had $85 million in the bank were wrong, saying that the figure was nearer $65 million.

He pointed out that even though the Navajos were the largest tribe in the country, their funds only represent less than $1,000 per Navajo.

At that same press conference, he said he expects to receive and then act quickly upon a proposal to nearly double the membership of the tribal Council.

But be cautioned to those who wanted a bigger Council that this does not necessarily mean a better functioning Council.

Efforts were underway, Udall said, to give tribal governments more authority over their own affairs “on as broad a basis as they indicate they can handle.”

But he worried that a large Council would result in many important issues getting bogged down in debate. To avoid this, he urged tribal governments to invest a lot of power in their chairman.

“A tribal council can be unwieldy,” he said.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow