‘Frybread Face and Me’ A universal film encapsulates the Diné way of life

Courtesy | ARRAY Company

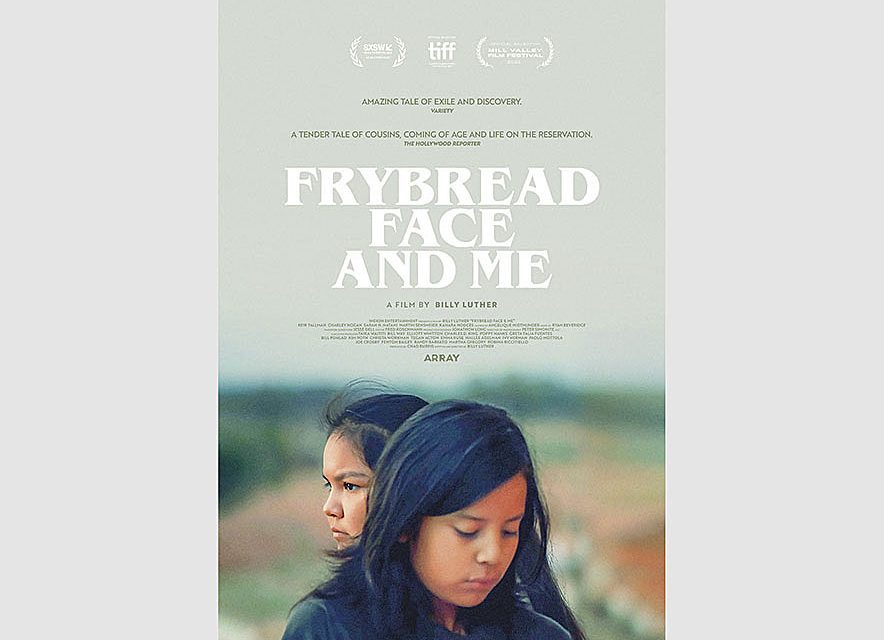

The narrative dramedy film, “Frybread Face and Me,” made its debut premiere on Netflix on Nov. 24 and has since been streaming in the top 10 in the U.S. The film is directed and written by Diné/Hopi/Laguna Pueblo Billy Luther, who is originally from Winslow, Ariz., and currently resides in Los Angeles.

TWIN LAKES, N.M. – During summer days spent at grandma’s ranch, reality sinks in by way of dirt, sheep bleating in the distance, and grandma’s hogan waiting for us. These days, the smell of dirt, sheep corral, and grandma’s words have woven us to self-reflect and find hózhó. At least that is what runs through the coming-of-age dramedy “Frybread Face and Me” from a Diné perspective.

Courtesy | Andi Parmalee

Diné director, producer, and writer Billy Luther, of Winslow, Ariz., recently released his first narrative dramedy film, “Frybread Face and Me,” which has become the U.S. favorite on Netflix for the past two weeks since its debut on Nov. 24. Luther has made several documentaries and short films in the past few years. He has opened doors to first-time Diné actors.

The 88-minute narrative film, directed and written by Billy Luther, who is Diné/Hopi/Laguna Pueblo, premiered on Netflix on Nov. 24.

Since the film’s debut, it has been sitting in the top 10 on Netflix in the U.S. It is currently at number four, which Luther jokingly said was no surprise as four is a sacred number.

The film takes place in the summer of 1990, and 11-year-old Benny, played by Keir Tallman, is on his way to spend his summer at his grandma Lorraine’s (Sarah H. Natani) ranch in Arizona.

This allows Benny, who lives in San Diego with his parents, to reconnect with his roots. It is where he meets his cousin, Dawn, aka Fry (Charley Hogan), who teaches him about living in the Navajo Nation and to live in hózhó.

“We all remember going back to our grandmothers on the rez,” said Luther, who is ‘Áshįįhí and born for Kiis’áanii. His maternal grandfather is Tł’ízíłání, and his paternal grandfather is Kiis’áanii. He is originally from Winslow and now resides in Los Angeles.

“It was just kind of (an) interesting look of an experience I had with my traditional cousins who lived on the rez,” Luther said.

What makes the film different is the Diné slang, jokes, and humor because it was not forced. Nor were Diné bizaad words mispronounced because they were immersed throughout the story by a handful of Diné casting.

“I love humor, and I write that, and that has always been present in my life,” Luther said.

What capsulated the mood and tone were the specific details in the film, like Grandma Lorraine’s sheep corral with wooden pallets and wire fencing; the interior/exterior of the trailer home with utensils, tables, chairs, and television; and the interior/exterior of the hogan with woven rugs.

“We had a lot of Diné crew in the art department who knew what (the grandmother’s) corral looked like,” said Luther. “How to build it, the hogan, they knew what was inside. In the trailer, they knew exactly what type of utensils and appliances.”

Luther admires attention to detail because having a Diné crew in all departments means there is no need to try hard to create a replica of what life on the reservation looked like when it is how we Diné continue to live.

Authentic to its core

Bonding in different worlds, the two young Diné cousins become familiar with one another during a summer herding sheep on their grandma’s ranch, all while learning progressively about their family’s past and themselves.

Courtesy | Cybelle Codish

A still photograph from the narrative dramedy “Frybread Face and Me” stars Benny (Kier Tallman) and Dawn, aka Fry (Charley Hogan). They debut in this narrative dramedy film about two coming-of-age kids meeting at their grandma Lorraine’s (Sarah H. Natani) ranch in Arizona during the summer of 1990.

After 15 years of studying documentaries, Luther admitted it was a bit daunting as his first narrative feature because he spent roughly 10 years on this project.

“To finally see that work that not only I put into it but everybody, the crew, the cast, the producers, the investors, all of that, they all believed in the story,” Luther said.

Luther feels the film was successful because everybody put their heart and soul into it.

“I think Native storytellers need to exist because we have to tell our stories,” Luther said. “We need to bring our experiences to these stories and characters.”

Although studying film at Columbia College in Chicago did not precisely go as he planned, Luther became involved with volunteering in film festivals, where he was able to begin his film journey while living in Los Angeles.

While Hollywood continues to fill Native roles with non-Native actors, Luther suggests Hollywood needs to realize that there are many unique stories and perspectives from Native communities.

An authentic and meticulous film of honest storytelling is what the audience loves, whether Native or non-Native.

“What was exciting about it was Native social media (which) was so great and generous and everyone kept sharing it (the film),” Luther said.

With a small independent film, Luther said there was no funding to promote and advertise it, which led Luther to do what he knew best – he reached out to friends and encouraged them to share the film.

“It became a social media thing,” Luther said. “It was really exciting, and I was blown away.”

Not only did Luther share the excitement, but so did the cast, who were, for some, first-time actors.

Luther searched for a year for distribution for his independent film, which is challenging, whether it’s a Native or non-Native independent film.

As an example, he used Erica Tremblay’s new film, “Fancy Dance,” which is also going through the same process of being an independent film and seeking distribution.

Because of renowned producer/director Ava DuVernay, founder of ARRAY, which had an established partnership with Netflix, “Frybread Face and Me” could stream.

Creating a realistic location

Originally, Luther intended to film on the Navajo Nation, but due to the pandemic’s peak, the Nation was closed to visitors and filming during the summer of 2021.

Faced with that obstacle, an alternative was to film in New Mexico, which provided a tax incentive and is a great location for independent films.

The film was shot in Santa Fe, with a plot of land used for the setting of Grandma Lorraine’s ranch where hues of yellow, blue, and purple illuminate old cars, a mechanical bull made of padding and a barrel, and the essence of what surrounds the reservation.

Casting was done by Midthunder Casting, based in Santa Fe, which top casting director Angelique Midthunder heads. She previously supported efforts in casting for the hit series “Reservation Dogs,” directed by Sterlin Harjo, who is Seminole/Muscogee, and Taika Waititi of New Zealand, and the drama film “Drunktown’s Finest,” directed by Sydney Freeland, Diné.

Watching natural talents like Charley Hogan, who plays Dawn, also known as Fry, and Keir Tallman, who plays Benny, was almost like seeing our childhood unfold because of the reality of growing up on the reservation.

Revising and reviewing

The script collected dust for a bit, and Luther revisited it.

“The seed was planted ten years ago and then, you know, really, started going full force with it like five years ago,” Luther said, as he wrote the first draft of the script five years ago pre-pandemic.

“We have so many stories to tell from the Indigenous perspective, from Indigenous lens,” he said. “There’s so much untouched stories that are definitely unique.”

According to Luther, Canada is a step ahead in media and television, and film from the U.S., as he said, is lagging.

Luther intended not to emphasize his film as a Native film but rather to stay consistent in his story.

“Once I did that, I think all the pieces kind of fell together, and what is exciting now is people seeing it, and it’s resonating with them, and they’re feeling something,” he said.

Even non-Natives were reaching out to Luther personally and sharing that the story moved them as it made them think about and realize their family values and traditions.

Luther’s parents worked for the railroad in California and often visited his family in the Navajo Nation and Laguna Pueblo.

Luther encourages those seeking work in the film industry to continue to believe in their stories and determined efforts, as it is a challenging field to become part of.

Luther’s past films include the award-winning documentary “Miss Navajo,” which premiered at the 2007 Sundance Film Festival and aired nationally on PBS’ Independent Lens that same year.

His second documentary feature, “Grab,” premiered at the 2011 Sundance Film Festival and aired nationally on Public Television that year.

Additionally, his latest short documentary film, “Red Lake,” had its world premiere at the 2016 LA Film Festival and was nominated for Best Documentary Short at the 2016 International Documentary Association Awards. In 2018, he launched his web series “alter-Native” for PBS’ IndieLens StoryCast.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow