Diné student honors family at exhibit, performance

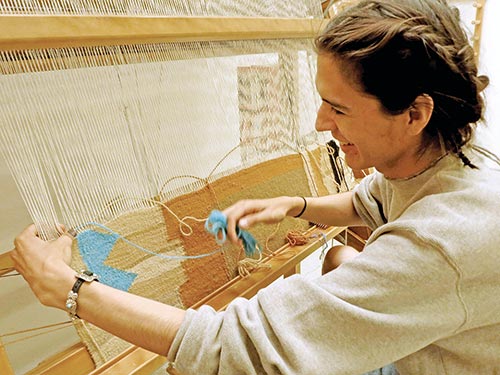

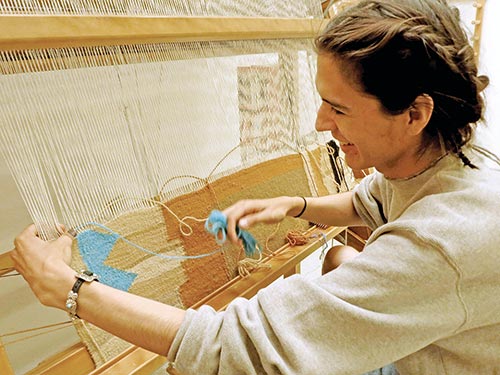

Submited UNM fine arts student Eric-Paul Riege, Diné, works on a weaving that will be integrated into his larger fiber art installation during a one day pop-up art experience in front of Zimmerman Library in Albuquerque on April 28.

ALBUQUERQUE

In the 1930s, Angela Ashley, a Diné weaver from Burnt Water, Arizona, lost most of her sheep to the Bureau of Indian Affairs livestock reduction.

“She lost hundreds of sheep,” says Eric-Paul Riege, Ashley’s great-grandson.

Submited

UNM fine arts student Eric-Paul Riege, Diné, works on a weaving that will be integrated into his larger fiber art installation during a one day pop-up art experience in front of Zimmerman Library in

Albuquerque on April 28.

Riege is Naaneesht’ézhi Táchii’nii (Black Charcoal Streak of Red Running into the Water People), born for Béésh Bich?ahii” (Metal Hat People-German).

Recalling stories by his mother, Retha Duffy-Riege, he said the colonial government intervention devastated his great-grandmother.

“This was her livelihood. She depended upon it,” he said.

After their sheep economy was ruined, Riege’s family eventually moved to Gallup where he grew up.

Now, in his early 20s, Riege is completing a bachelor’s degree in fine arts with a minor in Navajo linguistics at the University of New Mexico.

Following in his great-grandmother’s footsteps, Riege is a fiber artist who works with a variety of natural materials and dyes. He’s also a performance artist and creates digital presentations.

As he works on a weaving in Masley Hall, an art building on the north side of campus, he shares more of his family’s history.

“There’s a belief that if you don’t finish a weaving, your life will not continue the way you want it,” he said.

Riege attributes his great-grandmother’s long life to her many beautifully woven weavings.

Passing away in 2005 when Riege was 10, Ashley lived to be 101.

Turning to the weaving he’s working on, Riege says that his work brings back good memories for his mom.

“When I beat the loom and my mom hears it, she says it takes her back 50 years when my great-grandmother was weaving and she was rolling balls of yarn for her,” he said.

When his mom helps him with a weaving, Riege says with a smile, the process creates a special bond.

“Every inch of the yarn goes through her hands and then goes through mine. I see that as a collaboration,” he said.

As he grasps a string on the loom, Riege relates how weaving becomes the teacher.

“If there’s a gap in your weaving, it’s telling you to slow down,” he said. “At the edges, if you pull a little too hard, that’s a sign that you’re angry. You never want to be angry when you’re weaving, because you’ll be able to see it all over the place.”

When this most recent work is finished, Riege says it will reflect both the federally imposed boundaries of the Navajo Nation and the much wider ancestral ones.

To read the full article, pick up your copy of the Navajo Times at your nearest newsstand Thursday mornings!

Are you a digital subscriber? Read the most recent three weeks of stories by logging in to your online account.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow