Teachers: ‘Immersion’ for Diné not working

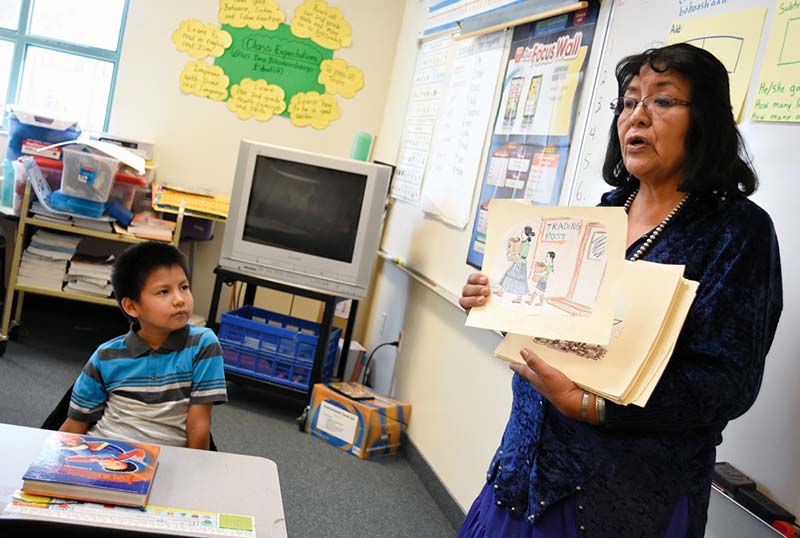

Navajo Times | Ravonelle Yazzie Second-grade Navajo language teacher Emma Dixon asks her students to describe a drawing in Diné bizaad on Nov. 1 at Tséhootsooí Diné Bi’ólta’.

FARMINGTON, N.M.

They were just young women when Rose Nofchissey and Louise Benally first started as Diné language teachers in the 70s.

Navajo Times | Ravonelle Yazzie

Second-grader Milen Chatter wears her tsiiyéél in the classroom at Tséhootsooí Diné Bi’ólta’. Tséhootsooí Diné Bi’ólta’ student teacher Jacqueline Chief mentioned that Chatter is consistent in wearing her Navajo traditional attire every week to school.

They remember fondly the days when the focus for Diné bizaad instructors was literacy in Navajo.

“At that time our focus was on reading and writing because all our kids spoke Navajo,” Benally said. “That was their primary language, their first language.”

Compare that to today when the primary language for Diné youth is English with very few fluent in their language.

“Now there’s really no one speaking Navajo,” Nofchissey said.

This has drastically shifted Navajo language instruction.

“You could do a lot more when they were fluent,” Benally said. “You could do a lot of stories, story-building. You could do plays. They could develop projects.”

Over the course of the last four decades, Benally, the secretary and treasurer of the Diné Language Teachers Association, has watched as Navajo children became less and less fluent.

“Now students are limited or non-proficient,” Benally said.

This is pushing Navajo language teachers to entirely change their approach to teaching the Navajo language from focusing on literacy to Navajo as a second language.

“It’s really difficult it seems to teach students a second language,” Benally said. “When they step outside the door they don’t hear Navajo.”

This was not the case in the 1980s when the majority of Navajos, around 93 percent, spoke their language, according to a study by Florian Johnson using U.S. Census data.

“When I was growing up there was a fine line between Navajo and English,” Nofchissey said. “My parents spoke only Navajo. So we were not allowed to speak English in our home. When we went to school we were not allowed to speak Navajo.”

However there was a stark shift once Navajo students were sent to attend boarding schools.

“Even though the parents speak Navajo, they don’t want their kids to learn Navajo maybe because they might not succeed,” Nofchissey said.

To read the full article, pick up your copy of the Navajo Times at your nearest newsstand Thursday mornings!

Are you a digital subscriber? Read the most recent three weeks of stories by logging in to your online account.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow