Diné painter questions nature of reality

Courtesy photo

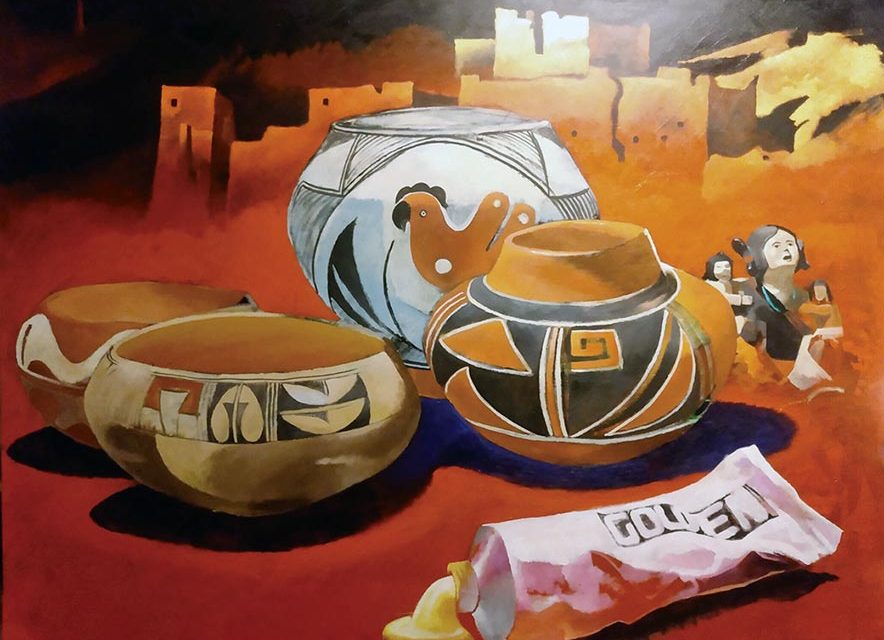

“Southwest Art” by Armond Antonio. Oil on canvas, 4 feet by 5 feet.

By Jada Griffin

SANTA FE

This land of enchantment speaks of another time sense than that of Western European linear time.

Here in New Mexico, we are aware of the bare geological bones of the earth. Where other American cities are paved, in less developed towns like Taos and Santa Fe, roads are often dirt.

The dirt connects us literally and directly to the skin of the planet on which we live, carrying us back to the origin birth that was the creation of the world.

Armond Antonio, a young Diné painter from Pueblo Pintado, New Mexico, on the Navajo Reservation, well understands this expansive and stratified sense of time.

The mesas and canyons of his homeland are saturated with a palpable spiritual force – a spiritual force that includes multiple layers of reality that have been absorbed into the myths and stories of his people.

“Southwest Art,” Antonio’s most recent work, when viewed up close pulsates with mysterious energy.

Artists often operate intuitively, hitching themselves by instinct to a skyhook, a tool that has the potential to catalyze a breakthrough in their work.

This has happened to me in my own art. Suddenly and without explanation, it will occur to the artist to incorporate a new element into a painting and this element all-at-once changes the emotional impact of the entire piece.

Arriving at the experience demands a “letting go,” a surrender of preconceptions, of one’s perceived ability to control the progress of the painting.

This “allowing” permits one to enter into the rhythm of a vaster and entirely interconnected universe. The blissful condition is trance-like. It has more power to affect the artist than the artist has power to stop it. A painting seems to arrive out of silence, emerging without the hand of the painter.

When Antonio includes into the foreground of “Southwest Art” an acrylic paint tube with yellow paint oozing out of it, a sudden breakthrough is recognized in his art. The paint tube, a surreal addition, causes a juxtaposition of unexpected elements.

We respond convulsively to the beauty in front of us, and we know too that the painting is an invention created in the mind of the artist. The painting is not the real world.

Beyond this, however, what Antonio effectively does in “Southwest Art,” with its Anasazi ruins in the background, its Indigenous pottery and Diné storyteller in the middle ground, and its paint tube in the foreground, is question the very nature of reality.

The artist makes it clear that the addition of the paint tube was a means to communicate to other Navajo artists accustomed to working exclusively with natural materials, that they can expand both their repertoire as well as their horizons by using industrially manufactured paint.

But in this masterful canvas, we travel forward in time from the back of the painting where the Anasazi ruins are, to the front of the painting where the paint tube is. (The paint tube, we know innately, rests in contemporary time.)

When we walk on the bare earth of the dirt roads of New Mexico, we mimic in reverse what happens in the painting and travel back in time to the very origins of our planet.

Within the realm of Antonio’s painting, as on the roads of New Mexico, we are time travelers from one energetic field to another energetic field.

Present time is one reality. Past time is another. The kingdom of the painting is one reality. The territory of the “real world” is a different one.

The painting, in fact, jogs us into an alternative reality, a reality where the thrust and forces of a vaster, interconnected cosmic fabric take over our fragile human capabilities.

Antonio’s universe is a universe of mystery that probes the unknown. If a painting can be its own reality, then there can be many other kinds of reality.

“Southwest Art” depicts not the world that we see, but one that the artist can claim is really there, a world that exists in a different dimension of time than the occidental consecutive one we are used to.

The beauty of Antonio’s painting goes beyond the ordinary limits of human consciousness into one that forms the foundation of experience, the ground of being.

Jada Griffin is a writer, writer, painter and art gallery director living in Santa Fe.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow