‘A wild ride’: Reining in the virus, contact tracers fight fear, COVID-19

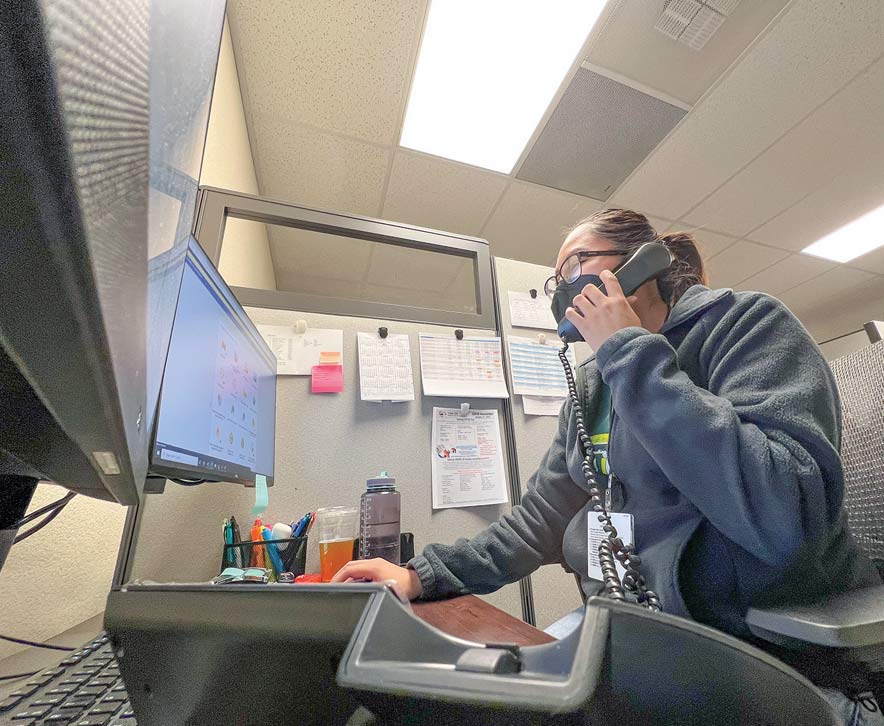

Navajo Times | Krista Allen Neenah Trujillo, a public health technician and a contact tracer for Tuba City Regional Health Care Corporation, sits at her computer inside her cubicle. Trujillo is part of the hospital’s contact-tracing program, in which she calls and communicates with COVID-positive patients and their close contacts.

TÓNANEESDIZÍ

Standing alongside her grandmother toward ha’a’aah every morning before sunrise, Krishanya Smith would pray to t’áá ałtsoní Áyiilaii.

“Bił naashnishígíí bił honílǫ́ǫ doo, t’áá shǫǫdí,” she’d ask Áyiilaaígíí.

She’d say reverently: “Díí naashnishígíí t’áá íiyisíí bee nizhónígo ída’diilnííł, dóó kǫ́ǫ́ nihik’éí dóó nihidine’é baa ída’diilnííł.”

Smith, who’s Bit’ahnii, is a public health technician and a naałniih nákéé’ na’ałkaahígíí, a contact tracer, for Tuba City Regional Health Care Corporation.

She’s part of a 10- to 12-member contact-tracing team, ch’osh doo yit’íinii ndeiłkaahígíí, to curb the spread of the coronavirus in the Tuba City Service Unit.

Since the early months of the coronavirus pandemic, contact tracers have worked to try to slow the spread of COVID-19 by identifying close contacts of people with COVID-19, often advising them to quarantine.

But contacting tracing is far more complex and stressful, said contact tracers at TCRHCC.

“It has been emotionally exhausting,” said Neenah Trujillo, a lead public health technician, and a contact tracer.

“You go through so many things different days,” she explained. “There’s something new every day.

“Some days I leave work just so tired from everything that I’ve heard: everything that I had to say,” she said. “I have left work crying, I have left work upset, but there are also days I left work happy because somebody got to go home from the hospital, or somebody recovered after having an emotional breakdown.”

Smith said attending cedar blessings and making time for hózhǫ on the TCRHCC campus helps. The hospital’s Native and Spiritual Medicine department provide a cedar blessing for its staff once a month.

“They (cedar blessings) help a lot,” Smith said. “We experience different emotions. There are some days I get very overwhelmed, especially during the first (wave) of the pandemic. It was very exhausting.”

Trujillo said a hataałii also prayed and asked Diyin Dine’é and Áyiilaaígíí to help and protect her and her team as they work – connecting the dots between a person with COVID-19 and their close contacts.

“Our team leaders reassured us that if we need somebody to talk to, they’re always there,” Smith said. “And the hospital’s online resources, that gave us some comfort personally.”

Trujillo said the hospital’s mental health technicians and counselors are on call around the clock for the contact-tracing team.

“I try to enforce that with my team to use those services because I’ve been using them,” Trujillo said, “and it helps a lot (to) do what we do.”

Contact tracing

The Navajo Nation has an army of 400 disease detectives to trace the contacts of every person who tests positive for COVID-19, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which has affected nearly every corner of the globe.

And those contact tracers communicate with thousands of people every day.

Contact tracing was once an obscure public health measure, but it took center stage in the fight against COVID-19 and the push to reopen Diné Bikéyah for business.

“SARS-CoV-2 is a novel virus, when it first showed up in the Navajo Nation,” said Arika Perry, the program lead for Navajo Area Indian Health Service’s contact tracing unit. “We’re prepared but we also had to adapt our public health, our clinical teams to respond.”

Perry is also the co-lead of the Navajo Nation Health Command Operations Center’s cluster investigations unit.

“And in that process, we’ve established that we need a team of individuals to not only reach out to patients; check on them and assess their clinical systems,” Perry explained Wednesday morning, “but also be the network that merges public health, clinical public health outreach, and coordination to these patients by phone.”

Contact tracers in Diné Bikéyah have been tracing the virus at a level that could be the envy of large cities. But it’s also hard work, said Lt. Cmdr. Annie Edleman of the U.S. Public Health Service’s Commission Corps. Edleman works for TCRHCC, where she’s the public health director.

“This work is hard,” Edleman said. “It’s emotionally challenging. It’s being present for people’s sadness and suffering.”

“This is the most challenging work that we’re ever going to be called upon,” she added. “Standing together as public health professionals and as health care workers to be together on the same team has been really important to make sure that we are dealing with this trauma the best that we can.”

Edleman said in 2020, when it was slow to develop an adequate contact-tracing program and a public health department for the hospital, many staffers such as physical therapists, dieticians, nurses, and dentists were reassigned and trained to be contact tracers.

The director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warned Congress in June 2020 that the U.S. would need at least 100,000 contact tracers, and billions of dollars to fund contact tracing programs.

“We started using CommCare in May 2020, and we started building this public health department (from July to September 2020),” Edleman said. “And we started hiring people, and the first contact tracers came on board in August 2020.”

CommCare is a mobile data collection application. Contact tracers use CommCare to conduct case investigation, case management, and follow-up, including referrals for essential services and resources.

Edleman said the hospital’s contact-tracing program built a system of how contact-tracing works.

“Basically, a person comes in to get tested (at TCRHCC in Tuba City, Sacred Peaks in Flagstaff, LeChee Health Facility, or at a TCRHCC testing site),” she said. “When the lab result comes and it’s positive, we get an automatic listing from the lab (twice a day). Those get distributed to both a provider and a contact tracer.”

The contact tracer then uses the hospital’s electronic health record and CommCare to begin their work. That’s when they pick up the phone and start calling to let the patient know they are positive for COVID-19.

“Then they give them instructions on isolation, and what to tell their close contacts, how to identify their close contacts, and what to do in emergencies,” Edleman said.

They also ask the patient about disease severity, if they have underlying conditions, and if they need resources – such as food, water, hygiene supplies, and a tent (for summertime because the Navajo Nation does not have isolation sites) – for their time in isolation or quarantine.

“Then they figure out how often to follow up with them (patients),” Edleman said. “Young, healthy vaccinated people may not need further follow-up whereas older people who are unvaccinated. People who have significant underlying conditions would have more frequent follow-up.

“And our goal is to complete case investigation within 24 hours of a positive lab result and deliver supplies to the home within 24 hours of that phone call,” she added. “And it’s been difficult over the last month. But usually, we’re pretty successful at that time frame.”

Emotional toll

Navajo Times | Krista Allen

Krishanya Smith, a public health technician and a contact tracer for Tuba City Regional Health Care Corporation, sits at her computer inside her cubicle on Feb. 4. Smith, along with the hospital’s contact-tracing team, is one the phone with COVID-positive patients 90% of their work time.

Contact tracers say it’s not unusual for people to cry on the phone when they talk to them. People vent about their fears and talk about missing work.

“A lot of people were scared at the beginning,” Smith said. “Some are still scared. But I think they do feel some comfort after we talk to them and giving them (a list of emergency numbers).

“So, we do our best to follow up with them at their request,” she said. “And the emergency room’s always open if they have any concerns.”

Trujillo said she and her team also get a lot of different emotions from the patients.

“It depends on how the person is feeling,” she said. “A lot of people don’t expect to get that phone call from us.

“In the beginning, we dealt with a lot of emotional people because we were uncertain of what COVID-19 was and what it can do,” she said.

When the John Hopkins’ Center for Health Security issued a national plan in April 2020, it reported that until there’s a vaccine, “management of the COVID-19 pandemic will rely heavily on traditional public health methods for case identification and contact tracing.”

“But now, people are a little more receptive. We try to assure them that they just need to isolate and to watch who they’re around,” Trujillo said.

Trujillo said she contracted COVID-19 twice.

Occasionally, contact tracers must call ambulances for the person on the other end of the line, said Edleman.

“When are we not on the phone?” asked Trujillo. “Ninety percent of our job is being on the phone. The rest, 10 percent, is on the computer typing out notes. We write out referrals – we spend a lot of time on the phone.”

Trujillo also oversees the hospital’s contact-tracing coordinators and the COVID-19 hotlines that patients may call to ask about results, questions, and ask for assistance.

“We have two hotline numbers that are available seven days a week, during the current surge,” Edleman said. “We’re answering (those) phones from 8 a.m. to 7 p.m. seven days a week to make sure that we instruct our cases on what to do in the event of an emergency; what an emergency is and what to do for non-emergencies. Every case gets (those) numbers.”

Omicron’s spread slows

After another brutal spike in COVID-19 cases and deaths, fueled by the Omicron variant, infections are declining in the U.S. and in Diné Bikéyah.

But experts say what comes next is hard to predict because often, it’s not known why the virus spreads the way it does.

The John Hopkins’ Coronavirus Resource Center reported on Wednesday more than 909,000 COVID-19 deaths, the highest known number of any country. Globally, there have been more than 401 million cases and 5.8 million deaths.

The Navajo Department of Health reported on Tuesday 51,279 cases and 1,625 deaths.

President Jonathan Nez has said that based on contact-tracing, it does not appear that new infections are occurring in businesses, but rather through in-person social and family gatherings where masks and other safety protocols are not followed.

He’s also said that the Nation is seeing cluster cases in Diné communities that have contributed to the high number of new COVID-19 cases.

“Contact tracers are finding that many of the new cases are due to in-person family gatherings where people let their guard down,” Nez said. “We have to do better, and we have to remain diligent.”

Up to 50% of transmission can take place before a person may never develop symptoms, and 40% of people may never develop symptoms but can still be infectious.

This means that people who are potentially infected need to isolate as soon as possible before they infect anyone else.

“Because of how widely transmittable Omicron has shown, it’s difficult to detect high transmittable areas,” DOH Executive Director Jill Jim told the Navajo Times Wednesday afternoon. “Omicron transmission was seen within families and in our communities, but we don’t have enough information of higher transmission factors.”

Perry said: “We’ve seen the virus in the U.S. and in the Navajo Nation where it’s been proven effective on continuing to decrease cases is masks and vaccinate individuals and booster doses.

“The transmission vectors of outside or inside the Navajo Nation, our response to continues to remain the same despite the jurisdictional boundaries.

“We want to continue to educate and advise our patients to receive treatment when they’ve been diagnosed or exposed to COVID-19.”

Lockdowns

Information published on a study by researchers at John Hopkins University indicates global lockdowns have been much more detrimental to society than a benefit during the pandemic.

Researchers concluded that they are ill-founded and should be rejected as a pandemic policy instrument.

Was an 18-month lockdown necessary in Diné Bikéyah? Perhaps it had little to no effect on COVID mortality.

“The closures were related to the two surges,” Jim explained. “So, when surges were trending high, extreme mitigation strategies were necessary because we did not know enough about the virus and we still don’t.

“A new variant can occur at any time but we are better prepared today,” she said.

But contact tracers aren’t finding what they found early in the pandemic, said Perry.

“We continue to see adaptation and involvement on not only with the evidence base of COVID-19,” Perry explained, “but we’ve also transitioned and shifted our response.

“So, we noticed that our patients are more educated about the infectious period of COVID-19: how to quarantine, the facts about the COVID-19 vaccine, and the treatments that are available.”

Perry added that there isn’t a lack of contact tracers in the Nation because there are several teams across Navajoland.

“Our program includes virtual public outreach, education, and reinforcement of isolation/quarantine guidelines,” Perry said. “Within our team here, that we lead, we have over 40 contact tracers employed at Navajo Area Office (in Window Rock), and our team coordinates with other organizations (such as COPE, the Community Outreach Program; Diné College, and other tribal 638 programs). Our team is very versatile.”

Jim added that the Nation has decided to reduce universal contact tracing and to begin focusing on priority population.

“In order to respond to the ongoing pandemic, we will have to assess burnout, capacity, and find new ways to respond to the public health emergency,” Jill added. “Nationally, some states and jurisdictions have eliminated universal contact tracing. We expect the CDC will adopt this soon.”

But, “it’s been a wild ride,” said Trujillo.

As a public service, the Navajo Times is making all coverage of the coronavirus pandemic fully available on its website. Please support the Times by subscribing.

How to protect yourself and others.

Why masks work. Which masks are best.

Resources for coronavirus assistance

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow