Advocates continue to urge congressional action on RECA

Special to the Times | Donovan Quintero

Maggie Billiman from Sawmill, Ariz., top center, holds signs in the air as she and others pose for photos on Monday in Window Rock.

By Donovan Quintero

Special to the Times

WINDOW ROCK – Maggie Billiman, who journeyed to Washington, D.C., over three weeks ago to advocate for an amendment to the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act introduced by Missouri Sen. Josh Hawley, voiced concerns about the lack of communication from Navajo Nation leaders.

Special to the Times | Donovan Quintero

Maggie Billiman from Sawmill, Ariz., carries signs that illustrate her thoughts about the status RECA is on during a protest walk that ended at the Navajo Nation Council Chamber on Monday.

Billiman’s commitment was evident as she walked to the Navajo Nation Council Chamber on Indigenous Peoples Day, where she expressed her appreciation that Navajo tribal leadership participated in a march to protest Republican House Speaker Mike Johnson’s unwillingness to allow for Sen. Hawley’s RECA legislation to be heard by Congress.

She added that neither Speaker Crystalyne Curley nor President Buu Nygren have maintained contact with the group of former uranium workers, downwind residents, and families affected by uranium mining-related illnesses since their protest.

Billiman added Navajo Nation Council Delegate Andy Nez, who represents her community of Sawmill, Arizona, never offered his support during the year and two months they’ve held meetings about RECA.

“No one ever came out to say, ‘You’re doing a good thing,’ especially when you want to be the advocate for the young ones, you should be out there and say, ‘Hey, you’re doing a good job, because these young kids for the next generation will come to support you,’ but nothing like that,” she said.

Working together with congressional partners

On Tuesday, Navajo Nation Washington Office Executive Director Justin Ahasteen highlighted the ongoing efforts to advance amendments to RECA.

Special to the Times | Donovan Quintero

Lori Lee Sekayumptewa, formerly a KTNN radio veejay, walks with her drum and feather as she walks to protest the continued stance of Republican House Speaker Mike Johnson’s refusal to introduce Republican Sen. Josh Hawley’s RECA amendment on Monday in Window Rock.

The NNWO director affirmed that the office is actively collaborating with congressional partners, including senatorial and congressional leadership, as well as coalition members to prioritize these amendments in the current legislative session.

“Our advocacy has successfully brought RECA to the forefront of congressional leadership discussions,” Ahasteen said.

The focus now shifts to including the amendments in remaining legislation, particularly the National Defense Authorization Act, before Congress reconvenes in December, he added.

From 1944 to 1986, around 30 million tons of uranium ore were extracted from this region, revealing the extent of mining operations. The Atomic Energy Commission was the primary buyer of uranium until 1966, continuing to purchase from the Navajo Nation until 1970, despite the emergence of commercial industry sales in the mid-1960s.

The unique geological makeup of the Navajo Nation positioned it as a significant source of uranium, a radioactive ore that gained high demand following World War II due to the development of atomic power and weapons.

Diné families lived near mines, sites

Many Navajo families have lived near the mines and processing sites, often relying on employment in these operations. Unfortunately, routine respiratory protections were not provided to the miners, resulting in devastating health consequences, according to Billiman.

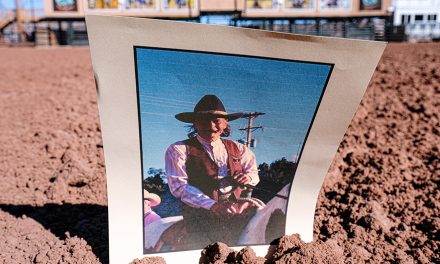

Special to the Times | Donovan Quintero

Alberta Begay from Cove, Ariz., carries a sign that highlights what uranium mining has done to her family during a march to advocate for the passage of a RECA amendment on Monday in Window Rock.

The Navajo uranium miners have reported alarmingly high mortality rates from lung cancer, tuberculosis, and other serious respiratory diseases, highlighting the human cost of resource extraction in the area, according to the EPA.

Following the Cold War, the demand for uranium dwindled as federal needs for nuclear weapons decreased, leading to the abandonment of hundreds of mines on Navajo lands. These sites were left uncovered and unremediated, with uranium processing facilities decommissioned by the U.S. government under problematic circumstances.

Radioactive mill tailings were merely capped with clay and rock, leaving behind a legacy of environmental and health hazards for surrounding communities.

Currently, there are approximately 524 identified uranium mine sites in the Navajo Nation, yet only 219 of those have allocated funds for cleanup and remediation efforts. This leaves a staggering 305 sites without any active plans to address the pollution and health risks posed to residents.

Cleanup at 7 abandoned uranium mine sites

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency announced progress in its efforts to address uranium contamination in the Navajo Nation by committing to cleanup plans for seven abandoned uranium mine sites. These projects aim to eliminate over 1 million cubic yards of contaminated soil and restore approximately 260 acres of land, benefitting communities in the Smith Lake and Mariano Lake chapters.

EPA Pacific Southwest Regional Administrator Martha Guzman stated the announcement, “marks clear progress on addressing the painful legacy of uranium mine contamination in Navajo Nation.”

She emphasized that the cleanup decisions were made in close coordination with the Navajo Nation government, to restore the land for unrestricted use by local communities.

The cleanup plans encompass the Mariano Lake, Mac 1 and 2, Black Jack 1 and 2, and Ruby 1 and 3 mine sites and will be conducted under the EPA’s Superfund authority. With these selected sites, the agency is set to clean up a total of over 2 million cubic yards of uranium mine waste on Navajo lands.

While the cleanup of seven mines is in line with cleaning up all the former uranium mines, a lack of action continues to raise concerns about the enduring impacts of past mining practices and the urgent need for comprehensive environmental restoration.

With the Senate already having passed the amendments, Billiman said they continue to urge House leadership to expedite the process by either bringing the amendments to the floor for a vote or incorporating them into an upcoming appropriations package.

Need for swift action

Ahasteen emphasized the need for swift action, noting that if Congress fails to act before its adjournment, the Navajo Nation will need to re-engage with a new Congress in January.

Special to the Times | Donovan Quintero

An activist against uranium mining holds a banner on Monday in Window Rock.

The advocates are calling for urgent legislative action to address the health and environmental impacts of uranium contamination in Cove, Arizona. Alberta Begay, whose sister has been battling health issues linked to uranium exposure, emphasized the importance of this advocacy trip, stating that they hope for tangible support for families and future generations.

Billiman articulated her frustrations regarding the lack of engagement from local leadership, despite the group’s ongoing efforts to bring attention to their plight. Both she and Begay highlighted the necessity for bipartisan support to advance their cause and acknowledged the challenges they face in accessing key congressional officials.

RECA was enacted in 1990 to provide compensation to individuals who developed health problems due to exposure to radiation from nuclear testing and uranium mining activities.

On Monday, Billiman and her family completed their walk at the front entrance of the Council chamber. The group took a few photos before departing.

“I’ve been thinking about like, today’s a special day for Indigenous Peoples Day, and I’ve been at home and can’t settle down, and I don’t want to give up on this. I feel like the Washington D.C., trip was the best thing that happened to everyone, and it’s positive,” she said. “We can’t give up the fight for this, for our people and all across the country. Indigenous day was a perfect day.”

The Navajo Times will reach out to Navajo Nation and federal leaders to get an update on RECA.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow