Former Bennett Freeze Area residents still waiting: Part I

Navajo Times | Krista Allen

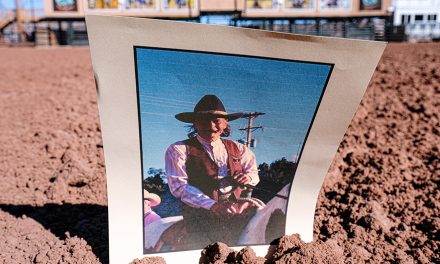

The late Vicki Rose Kee, 60, from Tonalea, Ariz., stands outside her home near White Mesa, Ariz., on a Saturday afternoon. Kee passed on Oct. 29. Her family and friends say she died waiting for a new home in the Former Bennett Freeze Area. Vicki Kee’s relatives and neighbors send their condolences to Kee’s children and mother, Mary Kee.

TÓNEHELĮ́Į́H, Ariz. – Lavonnia Begay wanted to walk from here to Washington, D.C., in service of a cause: to petition the federal government to help the Former Bennett Freeze Area residents.

Navajo Times | Krista Allen

Mary Kee, 80, stands outside her home near White Mesa, Ariz., on a Saturday afternoon. Kee said she has been waiting for a new home in the Former Bennett Freeze Area, where she raised a family.

Her young grandson pleaded with her to stay because of potential extreme weather and roadside dangers. She told him she would do it for the people – living in the nine FBFA chapters in Western Navajo – find justice.

“He cried,” Begay said. “I’m so sick of this – the Bennett Freeze!”

Begay, 63, grew up near White Mesa (in Tonalea, Arizona), where some residents still live in poor housing and home conditions after Bennett Freeze, a 1966 development ban that former U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs Robert L. Bennett imposed on 1.5 million acres of land claimed by the Diné and the Kiis’áanii.

The land dispute dragged on for 40 years, preventing around 8,000 Diné in the nine chapters from repairing and running utilities to their homes, opening businesses, and building schools – unless the Hopi Tribe approved the improvements. And open businesses and build schools.

U.S. Congress in 2009 voted to lift the decades-old ban.

Former President Barack Obama had cleared the way for federal funding that would help rehabilitate the area. Residents say $25 million was earmarked for FBFA residents, but they’ve not yet seen that. Where is it?

Some FBFA residents believe that the Diné leaders are using it for their personal use and their travels. Raymond Maxx, the former Navajo-Hopi Land Commission executive director, said there’s no $25 million. But there are the FBFA Escrow Funds, which is for FBFA residents.

“The escrow fund, there is $3.8 million – roughly $4 million – that was allocated to the nine chapters,” Maxx said. “Those are still sitting there after 10 years. It’s unused.”

It’s Navajo Nation funds with no strings attached, but part of the reason why the money is unused is because it has been tied up in tribal policy red tape.

Without bureaucracy, the NHLC would buy only materials, but the chapters would have to do assessments, make material listings, and provide labor.

“So, that’s kind of a way of stretching the dollar,” Maxx said. “And to have people that use those funds – put some sweat equity into it.

“The chapters, they don’t have capacity, the due diligence, and also labor,” he said. “We have a nonprofit called CHOICE Humanitarian that is willing to do the due diligence and provide labor. That’s why the funds have been sitting there for 10 years.”

Maxx said he encouraged the nine chapters’ leaderships to work with the nonprofit and use the funds for its intention: repair.

Read the full story in the Nov. 2 edition of the Navajo Times.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow