‘I wanted to be a Marine’: At home with 107-year-old Code Talker John Kinsel Sr.

Special to the Times | Melanie Cissone

Ronald Kinsel sits close to his Navajo Code Talker father, 107-year-old John Kinsel Sr., at their home in Lukachukai, Ariz.

By Melanie Cissone

Special to the Times

LÓK’A’CH’ÉGAI – It’s a Sunday morning in early December; winter’s begun to set in.

Step back in time. Imagine you’re a teenager or you’re in your early twenties. You’re awake before sunrise because your heavy-handed boarding school mandates church attendance, chores, both, or offsite work. If you aren’t away, you’re probably tending to what’s left of the livestock your family owns or working the homestead in other ways. Even if a daily newspaper was available to read or a radio broadcast to hear the next day, you might struggle because English isn’t your first language. How could you possibly know about the epic catastrophe occurring 3,100 miles away?

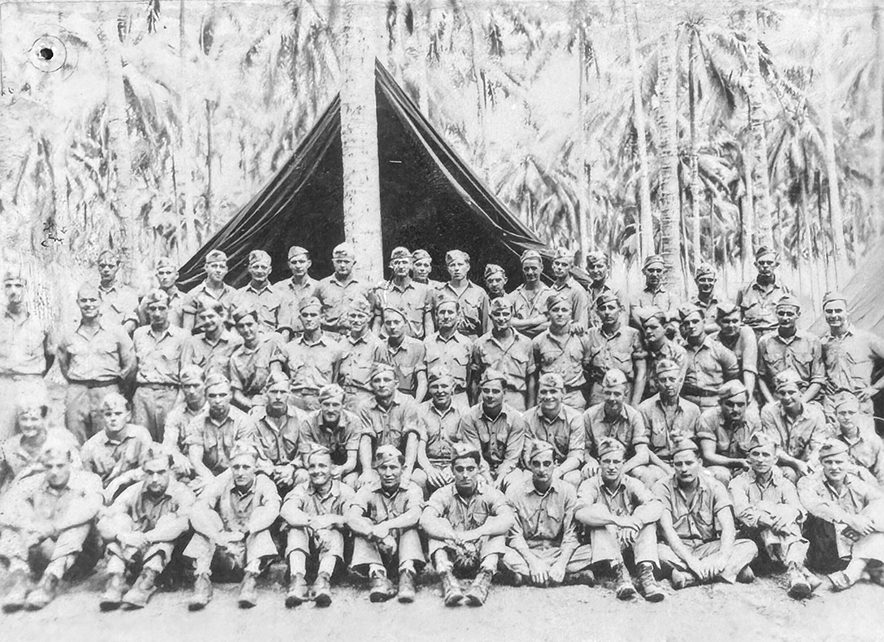

Courtesy | U.S. Marine Corps

The 1943 H&S Co. 9th Marines Signal Co, 3rd Marine Division. Navajo Code Talker John Kinsel Sr., bottom row, fifth from the left.

Those were the very circumstances of 107-year-old retired U.S. Marine Cpl. John Kinsel Sr. on Dec. 7, 1941, when the Empire of Japan attacked an unsuspecting U.S. Pacific Fleet and the Republic of Hawaii at Pearl Harbor. Little could he or hundreds of other Navajo men have known how radically their lives would soon change on a day that would “live in infamy,” to borrow from President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s December 8th declaration of war.

In a recent chat with Kinsel in the log cabin home he constructed, the Marine Corps Code Talker brings to life his boyhood days, his years serving in the South Pacific, and his home life as a husband, father, and as an integral—ahem—100-year-old member of the Lók’a’ch’égai community.

Kinsel is Kinłichíi’nii and born for Tábąąhá. His maternal grandfather is Naakaii Dine’é and his paternal grandfather is Bit’ahnii.

For a glance into a man’s life, understand that the memories are 80 to 100 years old and recalled in both Diné Bizaad and English. Know that birth dates weren’t recorded, that guessed-at or fabricated ages were used as markers for school attendance dates, and that no address records were kept during a migratory era. Nonetheless, despite impaired hearing and trouble mouthing certain words due to missing teeth, the centenarian maintains agency, preferring questions be directed at him even if he needs them repeated loudly and in both languages by his son.

Growing up in K’aabizhiistł’ah/K’aabizhii

Born in 1917 in Cove, Arizona, John Kinsel never knew his biological father, who died when he was young.

“Picked on by bullies, severe discipline, and inadequate food,” Kinsel remembers Fort Defiance Boarding School, which, at 6, he and his younger brother attended without any knowledge of the English language. Assigned the name John Williams at school, he later reclaimed his grandfather’s surname of Harvey. Shortly after his departure from the Bureau of Indian Affairs-run school, “The entire Fort Defiance Boarding School was transformed into a trachoma school in 1927,” says a 2010 Historic American Building Survey. Boarding schools were being converted into contagion wards or hospitals to contain rampant eye disease and tuberculosis.

It arises twice that John Kinsel’s little brother died “in school.” Trachoma can cause blindness and, untreated, tuberculosis can kill. An inherent lack of resistance was commonly thought to have made Native Americans susceptible to disease; it certainly couldn’t have been boarding school conditions. Ron Kinsel, 72, interprets. His father has always been of heavy heart about his brother’s death; the loss made Kinsel his mother’s only son.

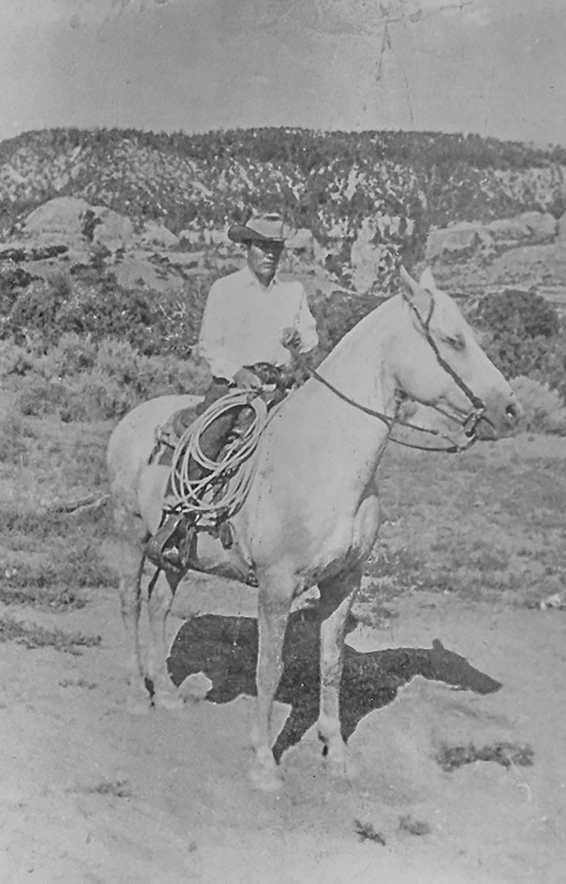

Courtesy | Kinsel family archive

Navajo Code Talker John Kinsel Sr. rides his rodeo horse, “Yo-yo,” a gift from a cousin.

Away from home as just a youngster, his remarried mother announced on his return, “Roy Kinsel is your stepfather.” Her new husband was a man from Twin Lakes, New Mexico, with grown children; young John had no choice but to adopt the Kinsel name.

The Kinsels moved from Cove to Lukachukai, where John’s influential grandfather homesteaded and raised a flock of 1,000 sheep, goats, and horses. A century later, only a few miles from the red sandstone cliffs of the northwestern spur of the Ch’óshgai Mountains where his mother first took him to live, Lukachukai, meaning “patches of white reeds,” continues to be Kinsel’s home. It’s where he and his late wife, Mary Elizabeth (née Shorty), raised their children and it’s where the war hero lives today in the care of a dedicated son.

Kinsel asked his grandfather to attend St. Michael Indian School where he graduated from 8th grade in 1937. In a 21-year-old alumni newsletter, Kinsel remarked after a tour and presentation about Code Talkers, “I remember this place well. It was like home.”

He fled Fort Wingate Boarding School on foot along Route 66. Without a plan, he intended simply to get to Santa Fe and ended up at St. Catherine’s Industrial Boarding School for Boy – “St. Kate,” he calls it – where he graduated on May 26, 1941. The attack on Pearl Harbor was still seven months away. A devout Catholic and a parishioner at St. Isabel Navajo Catholic Church and Mission in Lukachukai, he credits school prayer and songs with improving his English vocabulary.

Read the full story in the April 25, edition of the Navajo Times.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow