Letters: Response to ‘Man wants to revive lumber industry’ article

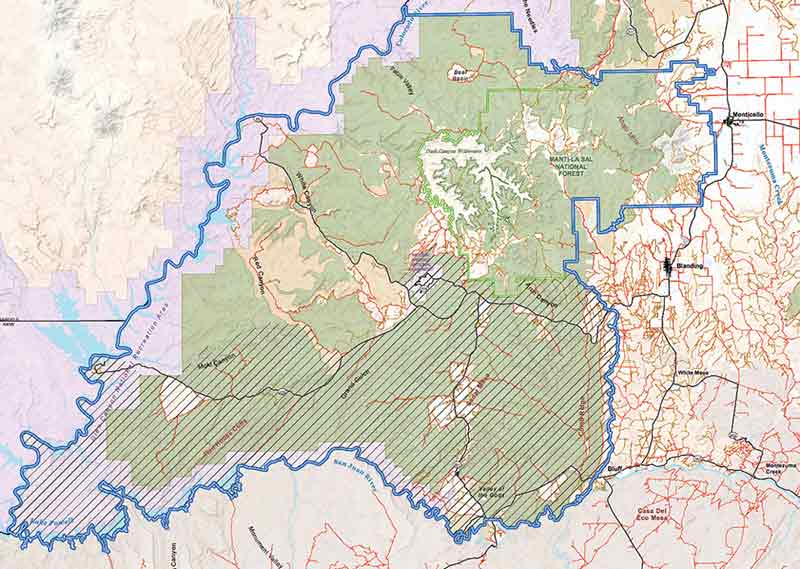

This map shows the proposed Diné Bikeyah National Conservation Area. The cross-hatched area indicates lands where the Navajo tribe would have a say in the management of the natural and cultural resources, for instance, medicinal plants. (Courtesy Utah Diné Bikéyah)

It has recently come to my attention that there are renewed plans to restart commercial logging in the Chuska and Fort Defiance forests. In July one of my family members attended a work session by the BIA and Natural Resource Division that was held for the Resource Development Committee on Managing Navajo Forestlands. Then two weeks ago, there was an article titled ‘Man wants to revive lumber industry” (Oct 22), in which a Sawmill community member expressed interest in restarting a timber company.

My sibling reported that in that July work session a timeline was laid out by the BIA and NN Natural Resource Division on managing the natural resources of the Chuska and Fort Defiance Plateau, including Navajo Mountain and Mt. Powell, since they too contain woodlands. The gist is that BIA and NRD, at the initiation of BIA are planning several resource extraction projects for the entire mountain range and other Navajo forestlands.

When it comes to managing our natural resources, including our forestlands, there is a lot to take into consideration. For one, the history of logging in Navajo forests goes back to 1888, when commercial timber harvesting began. At that time BIA owned a small sawmill, followed by more small sawmills, where 1.7 million board feet each year was cut and that annual amount was increased during WWII. By the late 1950s the Department of Interior funded studies, including one to establish an industrial sawmill. In 1960, the tribally owned Navajo Forest Products Industry (NFPI) began operations, with an annual harvest of over 40 million board feet. Meanwhile, NFPI’s peak employment was during the 1960s and by 1983, NFPI had a net loss of $5 million.

By 1990, Navajo community citizens recognized a multitude of effects from logging, such as erosion, the drying up of natural springs, the disappearance of medicinal herbs, the disappearance of wildlife, lack of pine regeneration, and clear signs of over cutting. It was then that my father Leroy Jackson looked into the forest management practices carried out by NFPI, Navajo Nation and BIA. The more he and other community members looked into how our forests were being handled, it became clear that Navajo forests were badly mismanaged. Directly affected community people who lived in the mountains had long noticed that their forest home was taking a toll from aggressive over harvesting.

To add salt to the wound, all lumber was sold off reservation. If the tribe wanted any lumber, they had to buy it back. Other disappointments included a lack of Navajo equity stakeholders. No shares were ever issued, nor was there any direct community oversight. As for regeneration and reforestation efforts- that was sparse, primarily absent and has yet to be fully carried out.

At the urging of Navajo forest communities with Dine C.A.R.E, the tribal council demanded an audit of NFPI’s operations. Finally in 1994, it was revealed that NFPI was over $ 20 million in debt, with over $ 6 million owed to the tribe in unpaid stumpage fees. Due to the gross mismanagement of NFPI, the tribal government shut down NFPI. The tribe took a loss that NFPI never repaid.

In a report by the NN Forestry Department dated from 1981, it was stated that it would take 160 years to catch up with the planting backlog, even if an extensive reforestation program was implemented. Also take into consideration that it takes a pine tree 125- 150 years to mature and data from 1990 stated that around 3 percent of old growth pine remained in our forests.

None of this information was shared or talked about at BIA’s work session and I didn’t see any of this in the article on ‘Man wants to revive lumber industry”. I would like to know how the BIA and Navajo Nation plan to repair and remediate past logging damage, such as erosion and lack of reforestation. Furthermore, what data, surveys, and studies do they have to presume that there is any worthwhile profit in starting up a logging operation? In talking with Chuska community members, we are not sure how many big diameter trees are realistically available for lumber. How much will infrastructure cost for logging operations? Many of the logging roads are big erosion gullies now. Will any of the lumber produced go to benefit the Navajo people? Lumber prices are dependent on the housing market and both markets are not doing great.

Since 1994, there has been a moratorium on commercial logging. Communities are still allowed to gather firewood and home building material. Those are reasonable needs. Commercial logging is another thing. With the real effects of drought and climate change, the last thing we need to do is cut our living grandfather trees. A healthy forest ties into our watershed, as well. Now and in the coming years, our water is what will keep our communities strong and prosperous. We need to take care of our water, forests and mountain- they have provided for us all these years. Let’s not forget that this mountain and forest is Ch’ooshgai, our sacred male mountain.

Any discussion on forest, water, and land management should involve the Navajo communities. Any natural resource management plan that does not inform or gain the consent of its constituents is a defunct plan that is doomed to fail.

Elias Jackson

Las Cruces, N.M.

(Hometown: Wheatfields, Ariz.)

Teachings we must pass on to our Diné children

Autumn is full of hope as families and schools come together anew. Optimism is high that every child will obtain knowledge to improve their quality of life.

Traditional Diné taught youth to build ‘will power” as an indication of strength of character. Having ‘will power” was a guarantee of good decision-making and overcoming challenges in life. New Diné generations now learn the power of reasoning and making choices. Knowledge for living a long life with happiness is just as important today as it was to our grandmothers and grandfathers.

Formal education in America evolved over 400 years to its present state. In comparison, Diné participation in formal education essentially began 65 years ago after the Navajo-Hopi Rehabilitation Act (April 19, 1950). Prior to 1960, more children were out of school than in school and even if all wished to go to school, those schools didn’t exist. A flurry of activity in the 60’s built today’s community schools and developed a cadre of Diné leaders and educators. This will always remain an amazing part of modern Diné history.

Despite this brief history, the extraordinary success of individual Diné is phenomenal. Achievements are no longer an isolated case as Diné youth now travel to all corners of the world with experiences in foreign countries and cultures. Graduations have become a celebrated rite of passage from Head Start through high school and each year increasing numbers of college students reach the heights of master and ph.d levels. Many graduates have exemplary professional careers and serve as pathfinders for our nation. All of this warrants our pride in Diné youth.

So, what about the thousands of our young people who find themselves on a different path and whose lives are a daily struggle. Today’s population of nearly 300,000 is 40 times greater than the 7,500 who negotiated the 1868 Treaty. We have not only outgrown our land base but know too well about social problems that negatively impact everyone’s lives. Sadly, there is growing apathy about inhuman acts of criminal behavior and levels of violence. Our grip on moral standards is weak. We must regain the ‘will power” that once guided our people.

We must find ways to change the lives of our people for the better. We know change can grow out of despair and dissatisfaction. Change is possible when we support each other and create communities that offer hope. With negativity harnessed, our children will benefit from a safer world. A child blossoms when seeing acts of kindness and benefits from positive relationships with adults. Children need opportunities to learn and practice respect, responsibility, caring for others, and how sacrifice builds integrity. Those A-Z activities that feature rodeo, sports, tutoring, art classes, and culture sessions are desperately needed by our children.

The Navajo Women’s Commission encourages your support of good people in your chapter, tribal programs, or families who all work hard and have a commitment to community service. We must recognize and value the inherent dignity and potential of each child.

Vivian Arviso

Navajo Women’s Commission Chairperson

Traditional views on suicide

Some of the answers I come up with about this question: ‘Traditional Views on Suicide?” will have reference to my having many years of law enforcement experiences at the federal, state and tribal level, traditional counseling with Indian Health Services with Eastern Navajo and being a Diné Blessing Way Chanter for the last 25 years.

It appears that suicides reported in Navajo Country happen in surprising and in unbelieving ways. The victims were alone and in isolated, remote places. Majority were self-inflicted, ending their lives with weapons or ropes. Reaction from family will be upsetting, angry, regret, and do not wish to be probed for answers to suicide happening among them. I have seen two young ones commit suicide due to an accidental death of their loved one. This was probably my hardest and most painful to accept as being true.

This appears similar at other areas outside Navajo area where I investigated suicide. In one reference one said, ‘I have an appointment with a diesel, can’t be late,” and then walks out and faced his fate. Another one stood in front of a locomotive going at full speed.

From Diné Blessing Ways, the teaching of ‘Diné Life Line” and ‘Beauty and Sacred of One’s Life Given” bares or upholds messages to suicide. Those that gave life to Diné affords them to reserve the respect, the sacredness and love of their lives. When one is involved with negative conduct or attitude about ending of their respected life, the Holy One’s elements surrounding us feels their negative messages. If the one(s) carry through with ending their lives, there is sadness, of course. The truthful matter is a shame to the one that ended their life. A disgraceful atmosphere the one creates to his life and to his family and relatives. An angry atmosphere will also exist. These are never mentioned during the time of sadness. Diné will remain mute due to cultural reason and respect to families. The one separated from lifeline has crossed over into death’s domain. There will be memories and talk of one’s good deeds made when alive by friends, relatives and family. Many Diné will not dare to discuss this matter of the one that committed suicide.

The one that committed suicide also affects the living friends, relatives and families. The suicide has also tarnished with negative effects outcome on their lifelines. This stigma remains for a long time and sometimes other family members might say ‘doo diigis” (was crazy)”.

The respect, honor and love to the deceased are always present with each. This is shared by all the families, relatives and friends. This is why all elements put with the deceased is handled with great care. And it will hold true to the survivors with their grieving and healing.

In traditional Diné way, the respect to the deceased is observed for a new quarter moon, or it could be second or third new quarter new moon before a traditional ceremony is conducted in restoring harmony and a beauty way of life for the survivals. I put in this note that there are other traditional spiritual support that can be made for a troubled individual.

With the suicides, which I have seen, investigated and assisted families with, comforting counsel is probably close to 100. The suicides have happened at the hands of loved ones. Most of the suicides occurred in remote areas, inside a home, in the vicinity of a home, or in places, which the one has picked.

No matter how hard the public services people, relatives, friends, or family to try and understand suicide, suicide will remain with our cultural system throughout time. Maybe it serves us best to remind us living that we be at our most respectful ways for our lives. Life is created one time; it cannot be replaced. And to retain the unity of love, Ke’ and respect of ourselves and to all those surrounding us, especially our family as we all walk our lifeline. And no other human on this earth has control, prolong, end or give life. This is in the hands of those that gave life.

There are many counsels and teaching on suicide matter from Diné traditional ways. For references or questions to my views about suicide, I can be reached at 505-612-9974 or at 505-786-6309.

Richard Anderson Sr.

Crownpoint, N.M.

By not spaying and neutering, pets are spreading diseases

Out here on the Navajo Reservation stray animals are spreading diseases at an alarming rate. Lime disease, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, mange, and even rabies cases are being reported across the reservation. Many of these diseases are being passed from their animal hosts to human victims. As shocking as the outbreak of these diseases is, the first step in their containment is equally obvious, the number of stray animals that are spreading these diseases need to be reduced by the spaying and neutering of pets.

According to Navajo Animal Control, there is an estimated 200,000 to 400,000 stray dogs and cats living on the reservation. The dogs especially are the main problem out here when it comes to property damage. The stray dogs form packs that bring down the livestock, horses, cows, sheep, and goats. Each livestock that is killed means less money to support their families with.

According to PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals), another reason to spay and neuter your pets is because a female dog and her offspring can produce 67,000 puppies in only six years. In seven years a female cat and her offspring can produce an incredible 370,000 kittens. Sterilized animals live longer, happier lives. Spaying eliminates the risk of uterine cancer and greatly reduces the risk of mammary cancer.

Neutered males are less likely to roam, spray, or fight over the females. Neutering cats stop the spreading of feline aids and feline leukemia. The cost of spaying and neutering pets on the reservation is $80 to $89 and off the reservation it can cost you between $200 and $250. There are free clinics that come around and the Navajo mobile units travel out here as well.

Many Navajos resist having their dogs spayed or neutered. Some have told me that they want to be able to breed a litter of sheepdogs to watch their sheep in the future. This seems like a valid concern in a culture that depends so much upon sheep and good sheep herding dogs. However, the numbers are just not adding up. Two dogs are being harvested, trained and care for out of multiple litters of multiple puppies each litter. The rest of the puppies are put into boxes and abandoned somewhere to fend for themselves. This just makes the problem worst.

Rather than being part of the problem, imagine how much better it would be if every time that a sheepherder needed a new sheepdog he went to the rescue shelter and took his pick of one of the dogs just waiting to be adopted. These dogs already have had their vaccinations and are spayed or neutered.

I had a personal experience with a shelter dog named Jazzy. Jazzy was a rescue that did not have a home and even the veterinary wasn’t certain what breed she was. After we rescued her, we gave her to our best friends and they took her to their sheep camp. As they were gathering their sheep, Jazzy immediately joined in with the other dogs bringing in the sheep.

Remember that by not spaying and neutering your pets, they are spreading deadly diseases, not just to other animals, but also to humans. Lime disease, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, mange, and rabies. These diseases, when treated, are painful, but if not caught early can lead to death.

Pam Fowles

Chinle, Ariz.

SMIS honors new powwow princesses

St. Michael Indian School’s Social Powwow was full of laughter, prayers, songs, and dancing. We were blessed with singing by six drums Friday night and eight drums Saturday night. This has been the most drums ever. The gourd dancing and the teachings shared were a blessing.

Throughout the two days, we heard from elders who recalled the first time powwow dancing at the school was performed over 50 years ago by the late Lorenzo Yazzie during the early days of the school’s annual bazaar. The elders expressed appreciation for the renewal of the social powwow. Everyone was there to have fun and not for prize money.

We would like to give a shout out of thanks to the following:

- Southern Host Drum Big Red, Northern Host Drum Mountain Thunder, and the other drum groups – Twin Eagle, Blue Medicine Well, Krazy Kreek, Callin Eagle, Blue Bear, and Twin Star Jrs.

- Arena Director Dariel Yazzie, Emcee Kenny Brown, Head Man Dancer Jamal Jones, Head Lady Dancer Melia Anthony, and Head Gourd Dancer Alvin Tsosie for coming to our rescue.

- The ladies sewing circle from Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament who presented handmade Quilts of Valor to local veterans.

- The senior class of 2016 for helping feed everyone in attendance.

- Bernard Begaye for providing a PA system on short notice.

- All the dancers and visiting royalty for gracing us with your presence.

- Everyone who donated cans of food. We took 331 cans of food in various sizes and a box of baby food to the food pantry at St. Michael Mission.

Congratulations to our new powwow princesses: Senior Miss Hunter Begaye (12th grade), Junior Miss Jaelyn DeChilly (8th grade), and Little Miss Aaliyah Bob (4th grade).

On a personal note, thanks to our new powwow family for welcoming my daughter into the circle.

Diana DeChilly

Powwow Committee

St. Michael Indian School

St. Michaels, Ariz.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow