‘May we be strong, may our prayers be heard’: Lummi totem pole stops in Bears Ears, Chaco Canyon enroute to D.C.

Navajo Times | Sharon Chischilly

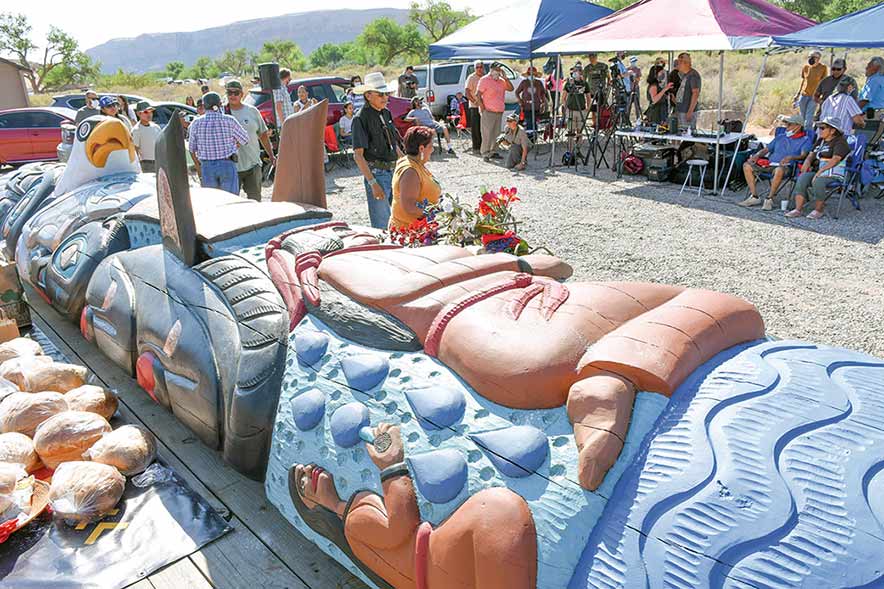

Rose Yazzie, 80, rests her hands on the 25-foot totem pole Sunday morning at Counselor Chapter House.

BLUFF-SAND ISLAND, Utah

The loaves of Pueblo oven bread were homemade and the thin-rolled Piki bread were brought by the Kiis’áanii.

The breads, along with all-natural handmade soaps from the Nizhóní Soap Company, LLC and lip gloss from Shundine’s Frybread Stand, were added to the individual gift baskets – assembled by the Women of Bears Ears – for the House of Tears Carvers and their allies from the Lummi Nation near Bellingham, Washington.

Other things in the baskets included ch’il ahwééhí, parched corn, naadą́ą́dootł’izhí, Pueblo pies and cookies, and a red bandana from the Bears Ears Prayer Run Alliance.

“We’re just sending off the carvers and their entourage with lots of food for the road – our hopes, our prayers,” said Ahjani Yepa, Jemez Pueblo, the co-founder of Women of Bears Ears.

“As women, we put our prayer into our food when we cook,” she said. “We make sure that we cook in a good mind, being happy and things like that.

“We’re making sure we’re praying for our landscape,” she said, “but also all of the landscape that is connecting this journey.”

Totem pole

Navajo Times | Krista Allen

A more than 24-foot-long, 4,900-pound totem pole carved from a 400-year-old western redcedar arrives at Sand Island in Bears Ears National Monument on Friday evening. A blessing ceremony took place the next day. Offerings were made and gift baskets of treats were given to the totem pole carvers, the Lummi Nation’s House of Tears Carvers, from Washington state.

More than 24-feet-long, the 4,900-pound totem pole, carved from a 400-year-old western redcedar, arrived at Shash Jaa’, Bears Ears National Monument, on Friday evening.

The richly decorated totem pole was created by the Lummi people, the Lhaq’temish (pronounced Lock-tuh-mish), and it’s meant to raise awareness about Native American issues and the need to protect sacred sites and water.

“This totem pole here represents our culture,” said Mark Maryboy, a Utah Diné Bikéyah Board member, “something that’s been created from the beginning of time.”

He added, “It’s all about conservation, culture, protection of public lands. It all ties together. It’s all one piece and it’s all about climate change.”

Tied down with lashing straps, the totem pole arrived on a flatbed trailer. The stop here is part of a 15-day cross-continent journey called the “Red Road to DC,” which started in the Lummi Nation last Wednesday, July 14.

The group on July 15 stopped at Snake River in Idaho, where the Lummi carvers met members of the Nez Percé Tribe who have been fighting to remove the Lower Snake River dams and restore free-flowing water and abundant salmon, steelhead, lamprey, and all other beings of their land.

The group on Saturday spent the day in Sand Island, where the Lummi carvers met with many Diné, Kiis’áanii, and Pueblo who are fighting to protect the Bears Ears and the Indian Creek regions.

The fight here is complex and multilayered – from on-the-ground stewardship work to suing the Trump administration to restore the original monument boundaries and protecting the integrity of the Antiquities Act, the law that gives U.S. presidents the authority to designate national monuments.

The group also stopped at Chaco Canyon National Historic Park on Sunday.

They will be visiting the Black Hills National Forest, the Missouri River, and Standing Rock in the Dakotas; White Earth, Minnesota; and Mackinaw City, Michigan, before arriving in Washington, D.C., on July 29.

“Our language and our prayers are appended to this totem pole,” said Delegate Nathaniel Brown, who represents Deinihootso, Tódinéeshzhee’, and Tsiiłchinbii’tó (Chiiłchinbii’tó), t’áá Dinék’ehjígo. “May this totem pole carry our plans for the future as it arrives in Washington, D.C.”

Brown said a ceremony for the totem pole – with thoughts of są’ah naagháii bik’eh hózhǫ́ – took place early Saturday morning on the bank of the San Juan River, or Tooh Bika’í.

“Our children, may they develop focus by building up essential clear-thinking skills, and speak our language,” said Brown, the chairman for the Diné Bizaad Subcommittee. “May our children pray and use our traditional plants and herbs for healing. And may they know the names of the water in our language.”

Brown continued, “May we start receiving rain again. I think of this as hózhǫ́. May we gather like this regularly. May our children become leaders in Washington, D.C., and learn our tradition and culture, and learn from our elders.

“May we be strong and may our prayers be heard,” he said. “May we receive blessings from the east, the south, the west, and from the north. And may we remember our Mother Earth daily.”

Brown said Diné need to start offering the earth tá’dídíín, ntł’iz, and naadąą – łigaii, łitsooí, and dootł’izh.

“We forget these things and that’s the reason for less precipitation than usual,” Brown added. “Not teaching – and speaking – our language may be the cause of heat and shifting weather patterns in the Navajo Nation.

“Now the coronavirus has entered our Nation,” he said. “So, may we get our rains back and may our plants grow again. And may our animals have food again.”

Protection of Bears Ears

Navajo Times | Krista Allen

The Women of Bears Ears includes a number of Native women, including Ida Yellowman, left, and Regina Lopez-Whiteskunk, far right. The women and girls presented the totem pole carvers, the Lummi Nation’s House of Tears Carvers, with homemade bread and gift baskets of treats.

Shash Jaa’ and the Grand Staircase-Escalante are treasured by many, but they are politically contested.

Former President Donald Trump in December 2017 announced deep cuts to the boundaries of Bears Ears National Monument, a vast, remote stretch of red rock canyons with Native American sites.

Shash Jaa’ was reduced by 85% and divided into two disconnected parks. Grand Staircase was also cut by 45%, paving the way for resource extraction and setting off a challenge in the courts.

With the historic nomination of Deb Haaland, the first Native Interior secretary, expectations are high.

Haaland in April traveled to Shash Jaa’ and to Grand Staircase as part of an Interior review of the boundaries in southern Utah. President Joe Biden initiated a review of the monuments on his first day in office when he signed an executive order directing his administration to examine both national monuments.

Biden is expected to reverse this decision and restore the monuments.

“The Bears Ears is a very sacred place,” said Ida Yellowman, a Diné from Tołchíí, Utah, who’s trying to push for Native American hunting rights at Shash Jaa’.

“I know that because I am a ceremonial person.”

Hopi Vice Chairman Clark Tenakhongva said “everyone” is somehow connected to Bears Ears in one way or another.

“The Hopi clans that came here, we left our marks,” Tenakhongva said. “We left our identities as what was told to us by the Creator when he accepted us here to this world – the Fourth World.”

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow