Sherman vs. Barboncito

Navajo Times | Donovan Quintero Jennifer Denetdale studies a photo July 6, 2017, during research at the Navajo Nation Museum in Window Rock.

Days, words leading to the negotiation of the Treaty of 1868

Navajo Times | Donovan Quintero

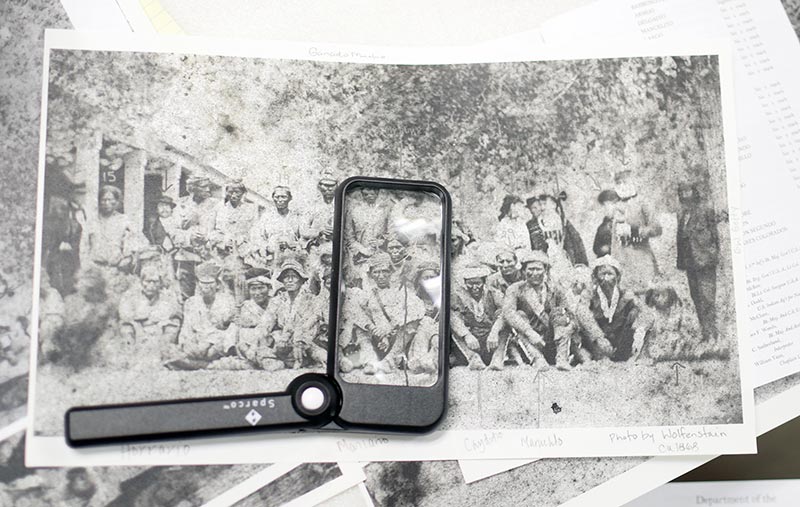

A photo taken by Swedish photographer Valentine Wolfentstein, believe to have been taken during the negotiation of the Treaty of 1868, shows Navajo leaders and military personnel at the Bosque Redondo reservation in Ft. Sumner, New Mexico.

They wore their best ceremonial clothing.

It wasn’t much, just tidbits of cloth they managed to make into shirts and pairs of pants, and some jewelry made of shells they picked from Calabasa they kept hidden from marauding bands of Comanches, Utes and Mexicans who never stopped terrorizing them.

The date was Thursday, May 28, 1868, the day “Capitone Grande” – Lt. Gen. W.T. Sherman – arrived at Bosque Redondo in Fort Sumner, New Mexico.

This was a momentous time for the Navajo people who had been held at the military camp since 1864. Their chance to plead to return home was here, now.

The West Point Army graduate who successfully fought in the Civil War came to the fort specifically to strike a deal with the Diné.

The great leader Barboncito, also known as Hashké Yich’I’ Dahilwo, was chosen to speak for his people.

Man from Sliding House

Already a veteran of many battles against the U.S. Cavalry, the man from Sliding House, located within Canyon de Chelly, wore his last pair of moccasins. He had made three pairs when he learned Sherman would be coming.

The meeting took place under a tent by the “Indian hospital,” located on the eastern side of the fort. There, Sherman, Samuel F. Tappan, both with the Indian Peace Commission, met with Barboncito, Delgadito, Manuelito, Largo, Herrero, Armijo and Torivio.

Not present, but playing an importantly equal role, were Diné women.

Jesus Arviso, 28, raised by the Navajos, would interpret from Navajo to Spanish and James Sutherland would translate Arviso’s Spanish to English.

Navajo Times | Donovan Quintero

Jennifer Denetdale studies a photo July 6, 2017, during research at the Navajo Nation Museum in Window Rock.

Then began the negotiations for some 7,176 souls. Secretary for the Council Proceedings Ashton White, who is identified as the secretary for the proceedings, recorded the meeting.

The transcript was provided to the Navajo Times by Aaron J. Roth, manager of Fort Sumner Historic Site/Bosque Redondo Memorial.

The weather in May was not typically hot and dry as was normal for Bosque Redondo – it was rainy with cooler temperatures.

The blessed rain seemed to hide the thousands of Diné who froze and starved to death since arriving to the fort, which Barboncito described as a “labor in vain.”

Sherman, the “blue coat with a moustache, who carried a long sword and a handgun,” began to speak first.

“The commissioners are here now for the purpose of learning and knowing all about your conditions and we wish to hear from you the truth and nothing but the truth,” Sherman said. “We have read in our books and learned from our officers that for many years whether right or wrong the Navajos have been at war with us.”

“The bringing of us here has caused a great decrease of our numbers, many of us have died, also a great number of our animals,” Barboncito said. “Our grandfathers had no idea of living in any other country except our own and I do not think it right for us to do so as we were never taught to.

“When the Navajos were first created, four mountains and four rivers were pointed out to us, inside of which we should live, that was to be our country and was given to us by the first woman,” he said.

Meager supplies

Sherman said Gen. James H. Carlton, who in September of 1862 began a “scorched earth” campaign against the Navajos, had removed them from their homelands in hopes of turning them into “agriculturists” with money the U.S. government gave them.

Despite an estimated half a million dollars a year spent on keeping the prisoners meagerly fed with a pound of bread and a pound of meat a day per family, despite the efforts of the Navajos who had farmed long before being taken to the “mere spot of green grass in the midst of a wild desert,” it was not enough.

Even the river system, the Pecos River that flowed through the area, killed the crops because of its high salt content.

A May 30, 1868, status report by U.S. Agent for Navajo Lands Theodore N. Dodd to Sherman revealed that of the 3,800 acres set aside for cultivation, 1,000 acres was to be farmed by the Navajos, which meant two-thirds of the crops went to the soldiers and government officials at the fort and the rest to the Navajos.

In 1865, more than 420,000 pounds of corn was yielded, 34,113 pounds of wheat was grown, and in 1866, a little over 201,420 pounds of corn and 2,942 pounds of wheat were grown. In 1867, Dood wrote was a total failure and nothing was grown.

“We find you have a done a good deal of work here in making acequias (irrigation canals), but we find you have no farms, no herds and are now as poor as you were four years ago,” Sherman said.

“That before we discuss what we are to do with you, we want to know what you have done in the past and what you think about your reservation here,” he said.

“It is true we were brought here, also true we have been taken good care of since we have been here,” Barboncito replied. “As soon as we were brought here, we started into work making acequias. We made all the adobes you see here. We have always done as we were told to … we never refused to do anything we were told to do.”

Barboncito said the livestock they brought with them all died, adding to the problems of living as captives in a country that was not their own.

“Nearly all that we brought here have died,” he said. “There are a great many among us who were once well off now they have nothing in their houses to sleep on except gunny sacks. When we came here there were plenty of mesquite root which we used for fuel, now there is none.”

To read the full article, pick up your copy of the Navajo Times at your nearest newsstand Thursday mornings!

Are you a digital subscriber? Read the most recent three weeks of stories by logging in to your online account.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow