Watching the war trail

Diné leaders become lawmen, leading to today’s police force

WINDOW ROCK

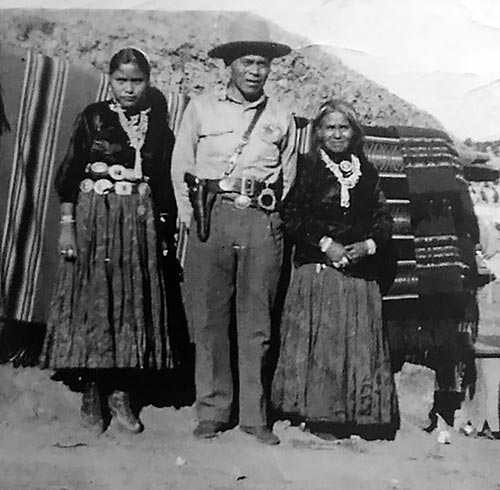

Courtesy photo

A James Hale family photo shows his late grandfather, Hoska “Hoskie” Thompson, who was a Navajo Nation police chief, with Hale’s late mother, Sarah Hale, left, and his late grandmother Nebah Thompson. Hale said his grandfather died in the line of duty on Oct. 21, 1949, while serving civil papers.

The theme for the 71st Navajo Nation Fair is “Respect, honor, remember our public safety officers,” and the history behind these words reflects the growth of a nation.

The three great leaders who negotiated the treaty for their people’s freedom in 1868 were once again called to serve after returning from Bosque Redondo, New Mexico – this time as officers of the U.S. government.

The tasks given to Barboncito, Ganado Mucho, Chief Manuelito and 129 other Navajos by Thomas V. Keams, acting Indian agent, were to guard the newly formed reservation and its borders, recover stolen livestock and arrest thieves – two years after returning from Hwéeldi.

Article I of the Treaty of 1868 states that “bad men” who commit a wrong against the Navajo people, would be “arrested and punished” by the commissioner of Indian Affairs through an Indian agent. Article X also specifically forbade the Navajo people from attacking wagon trains, taking mules or cattle that didn’t belong to them, as well as capturing or carrying off women and children, or scalping or killing white men.

While the killing of white settlers mostly stopped, stealing horses, sheep, and women and children began to rise. But in 1870, a drought across the newly formed reservation prompted warriors to take up arms once again so that they could feed their families, their communities and themselves.

The theft had become such a problem the military knew they had to put a stop to it before it got worse. But they did not want send in troops because it would create a bigger problem. That’s when they decided working with the local Navajo leaders they called headmen was the best approach. So they called on Manuelito.

According to Navajo Nation Police Capt. Mike Henderson, the Navajo leaders understood why their people were stealing. They also understood breaking the treaty would bring back the U.S. soldiers and their guns, jeopardizing the delicate balance that was made. With a cavalry of men, they worked with communities around the reservation, Henderson said. In eight months, they were able to return all stolen livestock back to the owners. When they completed their job, the cavalry was officially disbanded. However, Manuelito and his men continued “to watch the war trail,” said Henderson.

To read the full article, pick up your copy of the Navajo Times at your nearest newsstand Thursday mornings!

Are you a digital subscriber? Read the most recent three weeks of stories by logging in to your online account.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow