Tribal ranches: too much or not enough?

Navajo Times graphic | Courtney Notah

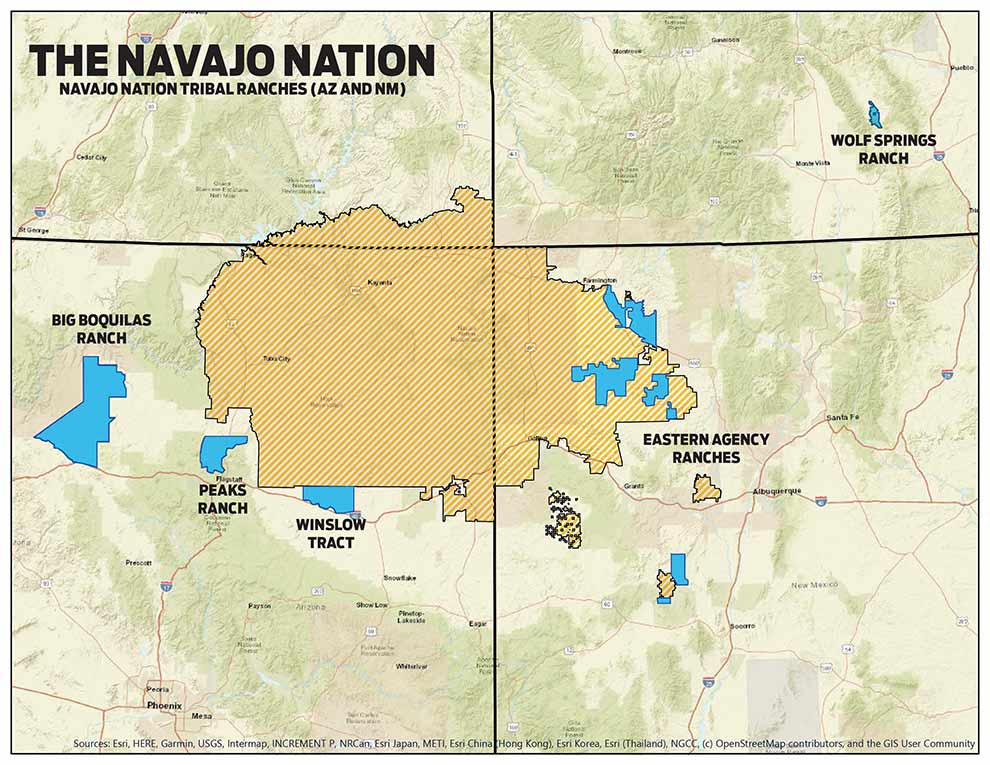

The Navajo Nation owns or has grazing rights to about 1.5 million acres of ranch land off the reservation, most of which can be leased by Navajo ranchers. (Thanks to Allison Gallensky of Rocky Mountain Wild and Christine Canaly of the San Luis Valley Ecosystem Council for GIS images of Wolf Springs and Boyer Ranch.)

WINDOW ROCK

When it comes to raising livestock, the Navajos have long been victims of their own success. After the Long Walk, the government issued the tribe 30,000 sheep and 2,000 goats. By the Dust Bowl of 1930, each Diné family had an average of 165 animals, with some families counting up to 2,500.

Even the disastrous livestock reduction effort of the mid-1930s did not make too deep a dent. By 1941 the Bureau of Indian Affairs counted 762,368 sheep on Navajo — 15-and-a-half for every man, woman and child. As early as 1939, BIA records indicate, the federal government was recommending the tribe lease ranch lands off the reservation to accommodate its herds.

But it wasn’t until 1954 that the Tribal Council developed a land acquisition policy and started snapping up ranches on and near its borders. Between 1957 and 1965, eight ranches were purchased, the largest being the Bar-N in Arizona, which went for $705,000.

Big Bo

The most infamous ranch purchase, of course, was the 491,000-acre Big Boquillas in 1987. Though it landed Peter MacDonald in federal prison after he bought the ranch for $26.25 million and sold it to the tribe five minutes later for $33.4 million — which most appraisers agreed was a ridiculously inflated price — it turns out 32 years later to have been a good investment for the tribe.

“From our standpoint, it’s one of the most beneficial arrangements the tribe has made,” said Tribal Ranching Program Manager Ferdinand Notah, citing the $545,000 annual income from the lease that is supplemented by $100,000 from the state of Arizona to mitigate damage by hunters who try their luck at the ranch’s estimated 4,000 elk. (While the tribal ranch program was instituted to help Navajo ranchers, Big Bo is leased to an Anglo — “No Navajo can afford it,” Notah explained — but there is a five-year plan to transition it to Navajo management. A railroad running through the ranch and nearby Seligman Airport provide opportunities for manufacturing and export that may be more lucrative than leasing to the rancher.)

With the recent purchase of the Wolf Springs and Boyer Ranch properties in southeastern Colorado, the tribe owns more than 1.5 million acres of ranchland, spread across 86 tracts in three states. Seventy-six Diné ranchers or associations are currently leasing the land. Most run 50 head of cattle or fewer, according to Notah.

In 2010, the ranching program went to a competitive bid process, replacing a secretive application process auditors said had no clear rules and invited favoritism. Some of the ranches have been withdrawn from use because of poor conditions.

Leasing rules

Other than for the Big Boquillas, applicants must be enrolled members of the Navajo Nation, not hold grazing permits for more than 75 sheep units, not hold full interest in a 160-acre allotment, be at least 21 and demonstrate an ability to pay the fee and manage the land.

Lessees are not allowed to live on the tribal ranches, which Notah says makes some of the more remote ranches undesirable and hard to lease. “The reason for that is that this is private land, and the property taxes go way up when you put a house on it,” Notah explained. The tribe did build a ranch house on the large, remote Peaks Ranch (now the Navajo Ranchers’ Association Ranch) that a ranch hand stays at during the summer and the ranchers can use during roundups (see accompanying story).

The ranching program pays about $300,000 a year in property taxes to 11 different counties, Notah said. It’s one of the program’s major expenses. The program’s $700,000 budget also includes about $300,000 in salaries, leaving just $100,000 a year for improvements at the ranches. One of the current projects is converting windmill-powered water pumps to solar, which work when the wind doesn’t blow and require less maintenance.

While the tribe has built some improvements on the ranches, lessees are responsible for maintaining them — but Notah said it’s hard to get ranchers to invest in the land when someone else may outbid them when their lease expires. In addition to the land, lessees have access to the tribe’s bull leasing program and quarterly trainings in herd health and best practices. “The quality of animals coming out of the tribal ranches has really improved,” said Notah, noting that many ranchers participate in LaBatt’s Native American Beef program, which accepts only grade prime cattle.

Much of the land within the ranches’ grazing area is owned by the state, Bureau of Land Management or U.S. Forest Service, which Notah said provides opportunities for the tribe to trade out parcels and consolidate its holdings. “The government doesn’t like checkerboarding any more than we do,” he noted.

A 45,000-acre trade with the state of New Mexico was recently completed, with more planned.

Wolf Springs

Almost as controversial as the Big Bo was the tribe’s $23 million purchase in 2017 of parts of two Colorado ranches totaling nearly 29,000 acres: Wolf Springs and the Boyer Ranch. These ranches, which include luxury cabins and sizable herds of big game, are not part of the Tribal Ranching Program.

They are managed instead by the Navajo Nation Fish and Wildlife Department. “It’s a unique property,” explained the department manager, Gloria Tom, “because of the high biological diversity as well as mineral resources. The thought behind assigning it to our department is that we would manage it not just for livestock, but as a multi-resource property.” So far, the ranch is breaking even, producing about $895,000 a year in hunting permits, mineral leases, hay production and livestock grazing leases, which Tom said is about what it costs to maintain the property.

What it hasn’t done is provide much benefit to the tribe. While two Navajos — a general manager and an administrative services officer — are employed by the ranch (stationed in Window Rock), the Nation kept on the non-Navajo folks who are running the 200-odd head of cattle and 900 bison. “It made sense for continuity’s sake,” Tom said.

There are two temporary labor jobs at Wolf Springs the department has been unable to fill. Located about 40 miles northwest of Walsenburg, Colorado, the ranch is too remote and too far from the reservation to make it attractive to most Diné. “It’s an eight-hour drive from Window Rock,” Tom said. “It’s not the kind of place where you can come home to your family on the weekends.”

Of course, the tribe did not spend $23 million on the ranch just to break even. Tom said the luxury cabins provide a prime opportunity for a hospitality enterprise. “We could provide a hunting experience, including staying in one of the cabins, as a package,” she said. “We could look at guided fishing and hiking trips, primitive camping … there’s a lot of potential there.”

For now, the department is focusing on continuing the existing uses while working on a plan to expand revenue at the ranch, she said.

Still not enough?

Notah said it’s not his job to criticize the Navajo Nation Council’s and president’s decisions, but it’s obvious he’s not a fan of Wolf Springs. “It’s too far away and too high-elevation,” he said. “They liked that it was in view of the sacred mountain, but Yavapai Ranch is much closer to Dook’oo’oosliid than Wolf Springs is to Sisnajinnie.”

Notah wanted the tribe to buy the 17,500-acre Yavapai Ranch instead. It’s close to the Peaks Ranch and much more accessible to Navajo ranchers than Wolf Springs. He still thinks it’s a good idea. One-and-a-half million acres in tribal ranches sounds like a lot of land, but Notah says it’s not nearly enough.

“We’ve got 13,000 grazing permits locking up the (trust) land,” he noted. “Meanwhile there’s 350,000 Navajos, at least some of whom are young people wanting to come back to the reservation and have animals. “If we don’t have some kind of land reform, and soon, we’re going to have a revolution on our hands.”

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow