A Blessing Way journey: Medicine man’s book prompts visit to Chinle

Special to the Times | Cindy Yurth

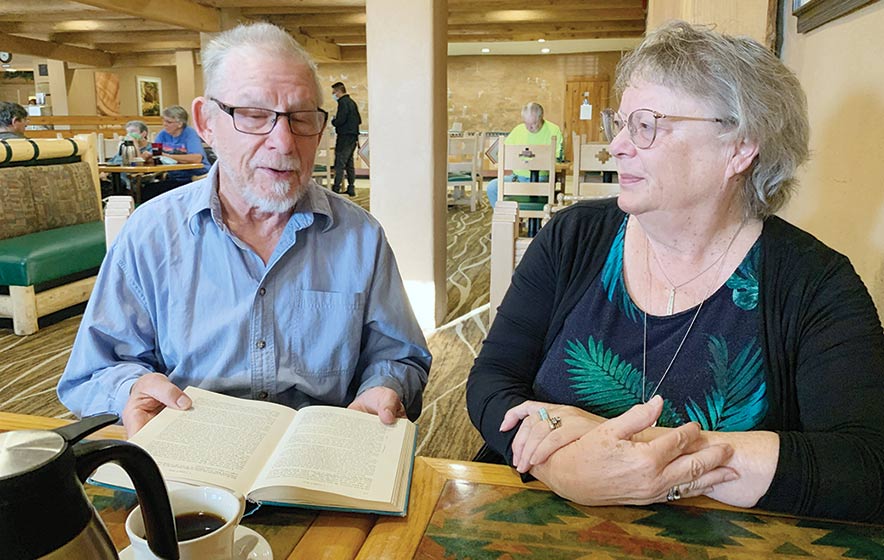

Jim Bodeen reads from Frank Mitchell’s autobiography “Blessing Way Singer: The Autobiography of Frank Mitchell” at Garcia’s Restaurant in Chinle last Thursday as his wife, Karen, listens.

By Cindy Yurth

Special to the Times

CHINLE

Sometimes, something someone says just strikes a chord, and you don’t really know why.

It can be someone from a different race or culture, even someone long dead. But after you hear or read their words, you’re not quite the same ever again.

That was the case for Jim Bodeen of Yakima, Washington. The 76-year-old poet and retired Spanish literature teacher stumbled onto, or perhaps was led to, the autobiography of the late medicine man Frank Mitchell about four years ago.

The connection was strong enough that last week found Bodeen and his wife, Karen, pointing their motor home to Chinle, where Mitchell had lived, in order to understand his words more deeply.

The couple had already been on the road since Aug. 16, making their way through the Sierras and ancient bristlecone pine forests to visit their son in Mammoth Lakes, California, for the first time since the pandemic.

Throughout their 53-year marriage, Karen, a fiber artist and retired bank president, had been pretty tolerant of her husband’s poetic whims. But she almost drew the line when they were planning the trip and he said he wanted to keep heading east from California to Chinle.

“Why you want to do this, I don’t know,” she recalls saying.

To which Jim replied, “OK, I’ll drop you off at home and head to Chinle myself.”

In a 53-year marriage, such talk does not fly. So there they both were at the Holiday Inn in Chinle last Thursday, knowing they wanted to lay flowers on Mitchell’s grave (after asking permission from two of his granddaughters) but not having much else in the way of plans.

They had visited Canyon de Chelly on their last trip to the Southwest, the trip where Jim first heard of Mitchell and the Blessing Way. But that was before they read the book. For Jim, the book and Chinle went hand in hand.

During that visit four years ago, Karen had been attending a quilting conference in Albuquerque while Jim, looking for something more up his alley, found a poetry conference to attend in Santa Fe.

Other than “Black Elk Speaks,” which he loved, Jim hadn’t read much Native American literature. When he heard Lyla June Johnston’s poem “Hozho,” it blew him away.

“She was quoting her grandmother and saying, ‘Show me something unbeautiful, and I will show you the veil over your eyes,’” he recalled. “I couldn’t forget that line.”

Shortly thereafter, Jim was reading an essay by Barry Lopez and encountered the word “hozho” again. Lopez defined it as “a spiritual invocation of the order of the exterior universe, that irreducible, holy complexity that manifests itself as all things changing through time.”

Lopez also mentioned the Beauty Way, or Blessing Way, which sent Jim on the Google search that turned up Mitchell’s autobiography with Charlotte Frisbie and David McAllester, “Navajo Blessingway Singer.”

Back in Washington, the book finally arrived at the Bodeens’ local library through inter-library loan. It was a crisp new copy, as yet untapped and unloved, and maybe that’s why it didn’t speak to Jim the first time he read it.

“I didn’t get beyond the individual lines,” he recalled. “I was disappointed with myself. I told Karen, ‘I think we’re going to go there.’”

On the journey, the couple read the book — an older copy that Jim had purchased on the internet — aloud to each other.

Mitchell had included in his book a lot of translated text from the Blessing Way songs — Jim calls them poems — and “those poems really began to open up once we left home.”

As they neared Diné Bikéyah, Jim read, “It is a sacred home that I’ve come to. I have come to the house of the Earth.”

They had driven through the smoke of a hundred forest fires, but 5,000-year-old bristlecones were still standing. Mitchell’s words seemed like survivors as well.

“The Blessing Way is outliving the white man’s culture,” Jim said. “It’s healing stuff.”

The Bodeens had written a letter to the Navajo Times hoping to connect with Mitchell’s descendants, but the two grandchildren who had responded lived in Keller, Washington and Mesa, Arizona.

This reporter contacted some of Mitchell’s relatives in Chinle, but most were born long after Mitchell died in 1967, hadn’t known him and didn’t feel compelled to meet his bilagáana admirer.

Frisbie, who also got word of the Bodeens’ quest, did reach out. Coincidentally, she had recently republished the book with a new forward and the Bodeens were able to buy a copy at Navajo National Monument on their way to Chinle.

Even without meeting Mitchell’s descendants, the trip to Chinle was well worth it, Jim said.

Something about reading the Blessing Way songs in the landscape that gave birth to them made them come alive. Canyon de Chelly residents they met, like Ben Teller and Lloyd Draper, helped them to understand the people and their land-based spirituality.

The little notebook Jim had brought on the trip was filling up with notes, scraps of poems, addresses of interesting people they had come across.

He felt hope for the battered Southwestern landscape they had traversed. It was, you might say, like a veil had been lifted. Beauty was everywhere.

“I hope I’m not overstepping in any way,” he said, “but I feel these Blessing Way poems are not just meant for the Navajo. I feel they’re meant for all of us.”

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow