A letter from 17 students: Proper – and truthful – Long Walk memorial began with plea from students

Navajo Times | Donovan Quintero

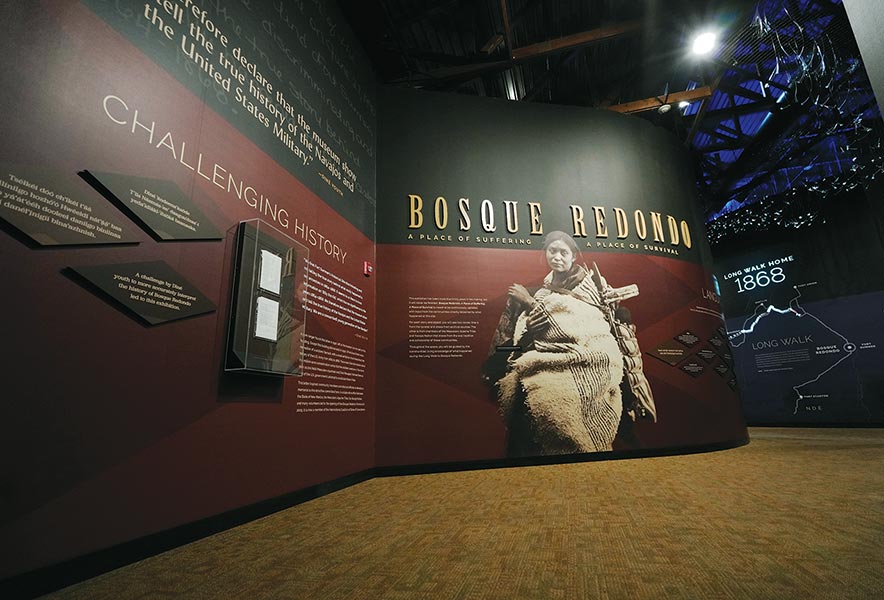

A mural and a letter written by students in 1990 started an exhibit called “Bosque Redondo: A Place of Suffering…A Place of Survival,” which opens on Saturday at 10 a.m. at the Bosque Redondo State Monument in Fort Sumner, N.M.

FORT SUMNER, N.M.

The story of what happened at Hwéeldi might have been lost forever.

Instead of learning how Bosque Redondo imprisoned 9,500 Navajo and 500 Mescalero Apaches, 17 Navajo students returning from a conference in Oklahoma City read a message on June 27, 1990, that compared their ancestors to a plague.

Aaron Roth, historic site manager at the Bosque Redondo Memorial at Fort Sumner Site in Fort Sumner, said an exhibit panel in 1990 read: “Newcomers to the west, are met with the same ferocity, from the Navajo and the Mescalero Apache, that plagued the Spanish years prior.”

In addition to the message, students were given a history lesson on William H. Bonney, an outlaw known as Billy the Kid, and Kit Carson, the U.S. soldier who campaigned against the Navajos by burning their homes and destroying their crops.

They decided to act.

No Long Walk history

Evelyn Becenti, who was a chaperone for the students at the time, remembered that at first, they had a hard time locating the museum.

“We looked and looked, and the only place close by that we could associate it with was the Kit Carson Museum,” said Becenti, who is now a retired teacher.

“So, pretty soon, we stopped there,” she said, “and we walked in, looked around.”

After walking through the museum, the bewildered group realized there was no history about the Long Walk.

“We were puzzled,” the Naschitti, New Mexico, native said. “As an adult, as a chaperone, I was shocked.

“I mean, there is nothing down here in Fort Sumner about the Long Walk, what our people went through,” she said.

The youth were disappointed, Becenti remembered, as they prepared to leave.

“We said, ‘OK, I guess that’s it. Sorry, I guess there’s nothing,’” Becenti said.

Then the group’s leader and conference coordinator Pauline M. Begay chimed in, remembered Becenti.

“‘Shall we just leave it? What do you think?’” Becenti recalled what Begay asked the students.

“And the youth said, ‘No, we got to leave something here, our thoughts – something,’” she said.

Begay, who worked with Save the Children, remembered how the children could not understand why the museum did not reveal the truth about the history of the Bosque Redondo Indian Reservation.

Writing a letter

Navajo Times | Donovan Quintero

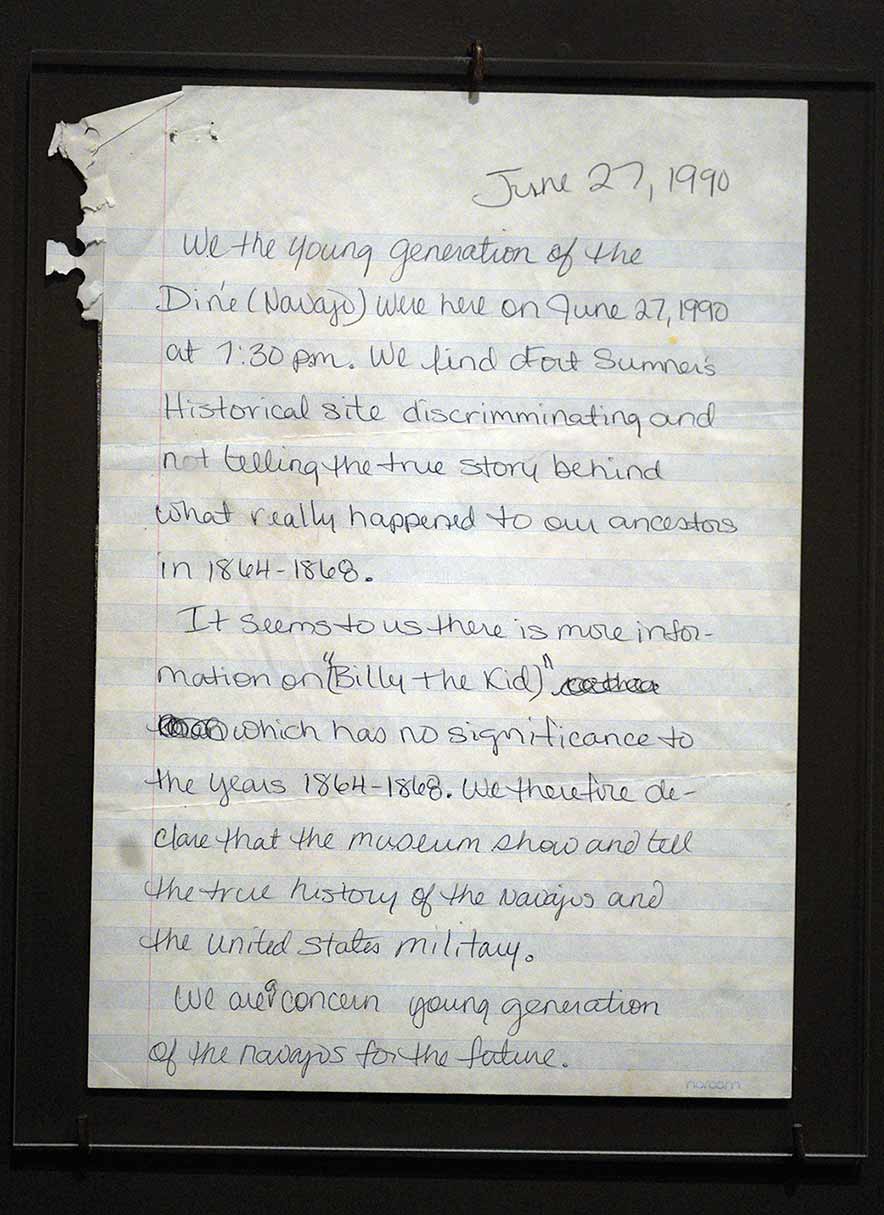

A letter written on June 27, 1990, by Navajo students is displayed at the Bosque Redondo State Monument, which will be part of an exhibit called “Bosque Redondo: A Place of Suffering…A Place of Survival,” which starts on Saturday at 10 a.m.

Begay said her grandmother passed down stories of what happened to them, which many Navajo youth do not have.

She felt the students deserved to learn more about their history because most of them at the time were getting accounts from movies.

“Except for maybe seeing western movies about Native Americans and cowboys and Indians and stuff like that,” said Begay, who would eventually serve on the Navajo Nation Board of Education.

So, the students began putting their thoughts together, with the help of Begay, and wrote a letter.

They wrote: “We the young generation of the Diné (Navajo) were here on June 27, 1990 at 7:30 p.m. We find Fort Sumner site discriminating and not telling the true story behind what really happened to our ancestors in 1864-1868.

“It seems to us there is more information on ‘(Billy the Kid)’ which has no significance to the years 1864-1868. We therefore declare that the museum show and tell the true history of the Navajos and the United States military. We are concern young generation of the Navajos for the future.”

“After that, we left. That is all we could do,” Becenti said.

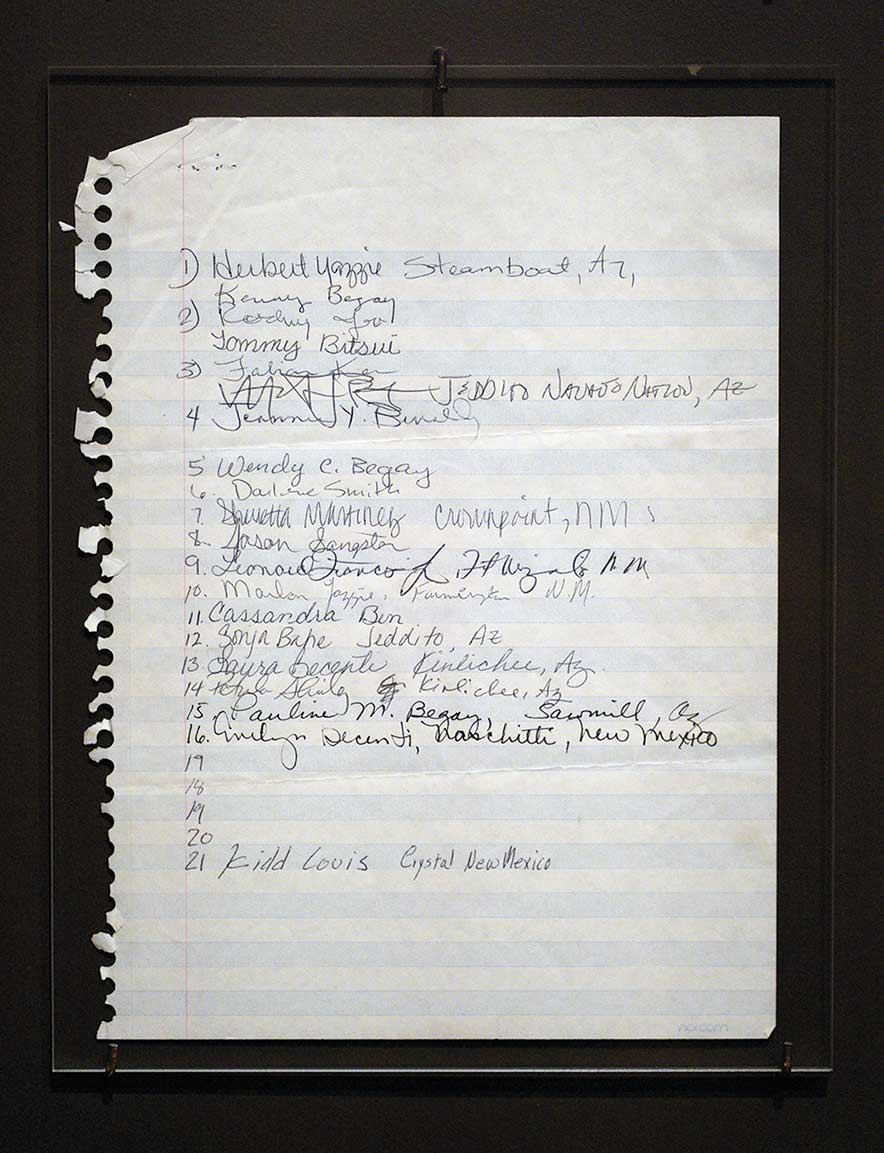

The students included Herbert Yazzie from Steamboat, Kenny Begay, Rocky Tso, Tommy Bitsui, Fabian Kee, Mat Fry from Jeddito, Jeannie Y. Benally, Wendy C. Begay, Darlene Smith, Sherretta Martinez from Crownpoint, Jason Songster, Leonard F. from Fort Wingate, Marlon Yazzie from Farmington, Cassandra Ben, Sonja Bahe from Jeddito, Laura Becenti and Petula Shirley from Kinlichee, and Kidd Louis from Crystal.

Proper truth

The community of Fort Sumner purchased a small section of the Bosque Redondo Reservation and deeded it to the state of New Mexico, according to Jose Cisneros, the former director of the Museum of New Mexico State Monuments.

The site was proclaimed a state monument on June 12, 1968, and two years later, Star Construction of Santa Fe constructed a visitor center for less than $40,000.

The visitor center – with an exhibit space of about 600 square feet – showcased and emphasized history.

Roth, who started as a ranger at the memorial site in 2014, said the 1990 letter set off a chain of reaction.

Three years after the Navajo students wrote their letter, the New Mexico Legislature in 1993 appropriated $100,000 to design a new center.

In 2002, former Sen. Jeff Bingaman appropriated $2 million through a federal bill.

By 2004, a new center was completed despite funding issues from the state, which had to fund half the cost.

The Navajo Nation AmeriCorps Project got involved and transported a sandstone boulder from the reservation in 1997 and placed it on the memorial site.

A metal plate was added to the boulder with a Navajo prayer inscribed on it, which former Navajo Nation President Peterson Zah dedicated in 1994.

The boulder is now on permanent display not too far from where the Navajo treaty was negotiated and signed on June 1, 1868.

A centennial reenactment of the signing took place on June 1, 1968.

Gregory Scott Smith, the former manager of the state monument, dubbed the area the “Navajo traveler’s shrine” after a Navajo hataałii blessed it in 1971.

Since the dedication, visitors have remembered Hwéeldi with small rocks they brought from locations all across the Navajo Nation.

A Purple Heart was also left by U.S. Marine Dean Begaye, who earned it after being injured by an improvised explosive device in 2005 in Fallujah, Iraq.

New exhibit

Navajo Times | Donovan Quintero

Names of Navajo students, including Pauline M. Begay, group leader and conference coordinator, and chaperone Evelyn Becenti, are listed on a paper that was signed on June 27, 1990.

Thirty-two years later, thanks to the students’ letter that told state monument officials to tell the truth, Roth said it has dramatically influenced an upcoming exhibit called the “Bosque Redondo: A Place of Suffering…A Place of Survival,” on Saturday.

The commemoration is a permanent interpretive exhibition that begins at 10 a.m.

The exhibition begins with the 1990 letter and a large mural of a Diné woman and her child who were at Hwéeldi when their photo was taken.

Exhibits of the Mescalero Apache, who were also imprisoned at Bosque Redondo, are also on display throughout.

The exhibition also highlights the boarding schools Navajo and Mescalero Apache children were forced to attend.

At the end of the tour, it ends with several clear plexiglass display cases with questions written on them, which visitors could write a response to on the plexiglass if they chose.

Becenti said she was invited and intended to go to the grand opening. Begay, who made a trip back to the Hwéeldi memorial site after 1990, said she noticed a slight improvement. She added she would not be able to make it but might plan to make a trip to the site soon.

Saturday’s event is free, but on Wednesday through Sunday, general admission is $7 for adults.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow