Indicting Canada’s, America’s racism: Chief’s book offers ‘real talk’ on systems arrayed against Indigenous

Courtesy photo

Chief Clarence Louie joins President Jonathan Nez at the launch of the Navajo-Hopi Honor Riders annual memorial motorcycle ride in 2019.

SANTA FE

If you’re ready for some “real talk” literary inspiration in 2022, take a dive into “Rez Rules” by Chief Clarence Joseph Louie, who has led the Osoyoos Indian Band of the Okanagan Nation in British Columbia for 35 years and counting.

Turning the pages of Louie’s book is like savoring grandma’s stew – hearty, with a kick, and a dose of tough love – and you won’t be able to put it down until you’re finished.

Courtesy photo

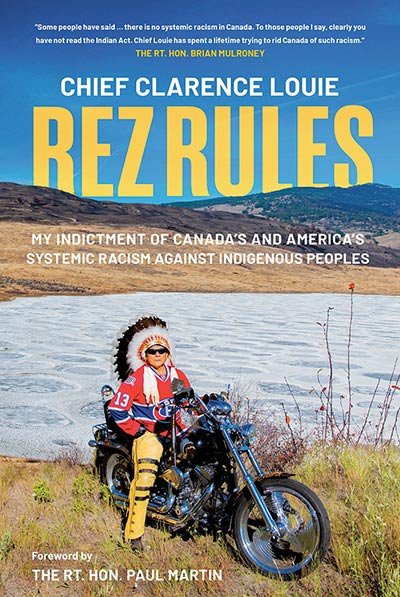

Rez Rules is published by McClelland & Stewart, Penguin Random House Canada, and is available in bookstores and on Amazon.com

In a rare memoir by a sitting tribal chief, Louie takes us on a journey through his upbringing on the Osoyoos “Rez,” his immersion into Native American studies, his commentary on the stark realities and injustices Native peoples have endured, and what it means for a tribal leader to put his people first in today’s complex world.

“A chief’s work is about and for the whole community they belong to and also extends to their tribal nation and the rest of Indian Country,” Louie said. “My legacy is not about ‘me,’ it’s about ‘we.’”

Hang on to your hat for a wild ride through the twists and turns of centuries of history that bridge the Canadian reserve and U.S. reservation experience.

Louie’s love for adventure, Native life and taking to the open road on his “iron horse,” coupled with stories of “Indian magic,” “Rez” culture, humor, sports and politics enthrall.

“Damn, I’m lucky to be an Indian!” says Louie.

Arbitrary borders

For Native people, systemic racism started in 1492, Louie writes.

“Before Columbus, tribes were self-sufficient and had their own economy,” he says. “After Columbus and colonization, tribes were economically and socially enslaved.”

Canada and the United States like to think of themselves as leaders of the “Free World,” says Louie, but it was free only in that they paid nothing for the lands they stole from Indians whose culture they then tried to destroy.

The reality is Natives were not included in the ideals proclaimed in the documents like the U.S. Declaration of Independence but instead continued to be subjected to racist ideals of the Doctrine of Discovery, Manifest Destiny, Indian Removal, and oppressive assimilation polices such as Canada’s Indian Act.

Louie’s Okanagan Nation territory (Nsyilxcén-speaking) spans south-central British Columbia and north-central Washington state, where Okanagan people live on the Colville Reservation.

“Like all tribal nations located near the forty-ninth parallel, the Okanagan people were split up by treaties that arbitrarily created a border between the Indian Reserve system in Canada and the Reservation system in the U.S.,” writes Louie.

“Since that arbitrary border was created,” he said, “my people have had to endure and suffer under various federal and provincial/state termination policies and programs intended to ‘kill the Indian in the Indian.’”

Government policy on both sides of the U.S./Canadian border viewed Indigenous people as “savages,” who lacked the same human and land rights as the English and French settlers who came late to this continent and presumed that since they had “found” it, they “owned it,” said Louie.

“So even though tribal nations can be so different, our Rez experiences and Rez life are what bind us,” he says. “My people, the Okanagan, are like all Native people in that we have an ancestral attachment to our territory that the colonial governments could not break.”

Dependency vs. self-sufficiency

Since being elected as chief of the Osoyoos Band in 1984 at age 24, Louie and the Council he heads have been leading his community, now referred to as the “Miracle in the Desert,” to prosperity.

As a chief, when it comes to the quality of life on your Rez, you only have two basic options, writes Louie.

“You can either become a chief who is an administrator of poverty and underfunded government welfare programs, or you can become a chief who creates revenue-generating jobs that make money for your First Nation,” he said. “It’s either a dependent (someone else feeds you) model or an independent (feed yourself) model.”

Louie has always emphasized economic development and self-sufficiency as a means to improve his people’s standard of living.

“Native people must change their mindset from spending money to making money,” writes Louie. “Socio-economic development is the foundation for First Nation self-reliance – our communities need to become business minded and begin to create their own jobs and revenue sources, not just administer underfunded government programs.”

All successful bands and tribes have one thing in common – none of them let Indian affairs run the Rez, he says.

“Indian affairs in North America is a multi-billion-dollar industry that has been built on the pain and suffering of Native people,” said Louie. “Operating from year to year on grants is not being sovereign or independent.”

It’s those tribes and bands that are generating their own source of revenue and creating an economic climate on the rez that are breaking away from federal government dependency, he said.

“No nation is free if it’s depending on foreign aid,” says Louie.

‘Reality costs money’

Louie says visioning, dreaming and ideas are free, but “reality costs money.”

“Everyone on the Rez says our future leaders are the youth,” says Louie. “Everyone says our number-one asset is our people,” he said. “Everyone says education is a priority. Nice words—but without economic development there will be no jobs for your educated people.”

Leadership requires team effort, good advisors, sound decision-making and compromise.

“History has proven that the best leaders are not the meanest and loudest but the most peaceful and kind,” he says. “Leaders lead by example.”

Louie’s leadership style is true to one thing – speaking the truth, even if it hurts.

“Everything has a price tag,” he said. “Real leaders know talk is cheap but governing is not.”

Louie believes job creation and increasing business revenue in a responsible manner can bring back the working culture and self-supporting lifestyle of his ancestors.

Fittingly, the Osoyoos Indian Band Development Corp.’s motto is “In business to preserve our past by strengthening our future.”

In Louie’s 35 years of leadership, the OIB has come to own and manage 11 businesses and be a part of five joint ventures in total employing more than a thousand people.

“Aboriginal people and governments must make economic development, self-sustaining job creation and business growth an everyday priority,” says Louie. “A real decent paying job that provides real opportunity is the very best social program on any Rez!”

Today, the Osoyoos Indian Band Development Corporation operates vineyards, a winery, retail stores, a concrete company, a championship golf course, a race track, gas station, cannabis stores, and a resort hotel and campground/RV park.

Over 18 two-year terms, Louie and Council have also emphasized the importance of maintaining the Okanagan language and preserving culture and heritage in all aspects of sustainable business development.

“We need leadership that isn’t in love with money but is in love with protecting the past, present and future of their Rez,” he says.

During Chief Louie’s tenure, the OIB has negotiated settlements of three Specific Land Claims, over 1,000 acres of lease developments, the acquisition of hundreds of acres of land, the purchase of an off-reserve business, and the construction of a daycare/preschool and grade school/gymnasium, a health and social services center, youth center and a cultural center.

“Today, many Rez people (especially on social media) talk about youth, and about how important the future generations are,” he said. “But they do this in words only. They don’t do the heavy lifting or figure out how to set money aside and create real job opportunities for those future generations.”

The ’Indian Problem’

Louie says it was the “Trail of broken treaties” that led him early on to engage in higher education. The ongoing injustices against his people became his calling.

After graduating from high school in 1978, he immersed himself in Native American Studies at the University of Regina (Saskatchewan Indian Federated College) and the University of Lethbridge and learned from the struggles and victories of his forefathers and contemporary American Indian Movement leaders.

“I decided to dedicate my life to doing something about this dysfunctional relationship between federal governments and Natives – a relationship that has so often been referred to by Canadian and American leaders as the ‘Indian problem,’” he says. “Indigenous people were referred to as savages to justify, both in religious and legal terms, the theft of Indian lands.”

Since then, in the U.S. and Canada, president after president and prime minister after prime minister sought to carry out cultural genocide against Native people – even after their tribes were either wiped out or forced onto reserves or reservations, he says.

“The racist abuse of power against all Native people was at the core of addressing the “Indian problem” in both of these countries,” says Louie.

Louie describes the cultural genocide of the Indian residential and boarding school era as the “greatest genocidal crime” ever committed in the histories of the two countries, which caused “irreparable damage” and led to intergenerational grief, alcoholism, hatred, mistrust and community and family breakdown in Native communities which persist to this day.

The legalized tormenting, abuse and killing of Native children was a national crime, a human rights violation, and a government cover-up at the highest level, he says.

“It’s time for Canada and the United States to acknowledge their historic war crimes against the First Nations people within their own borders,” he said.

Over centuries, through blatantly racist policies, generations of settlers and their governments tried to assimilate all First Nations into the Canadian and American melting pots.

“Thankfully, it didn’t quite work out that way,” he says. “… the so- called Indian problem has been around since 1492 and it’s important to note that those colonial ‘cattles on the hill’ in Ottawa and Washington have not managed to starve or Christianize all the ‘hostiles’ into submission.”

Louie says he will continue the fight for economic justice and the return of Rez land and the self-supporting lifestyle every first nation once had.

“… more than five hundred years after Christopher Columbus got lost and ‘discovered’ us, First Nations are now getting off our knees and back on our economic horse,” he says.

Reconciliation

Louie says law-abiding Canadians and Americans should be ashamed of how their government stole Native peoples’ Rez lands and it is the responsibility of today’s politicians to reconcile the Indian land thefts of the past.

He believes it would only take a few commonsense changes to not only right the injustices of the past but also give First Nations a chance at taking control of their own destiny.

“The conflict between Natives and Canada and the United States has always been and continues to be over land and unfilled treaty rights,” he says.

Reconciliation must translate into land justice and economic freedom for all First Nations, he says.

“…reconciliation must start with First Nations getting their old reserves and sacred cultural sites back,” says Louie.

Until both sides of the 49th parallel show themselves willing to be honest about the past and the ways in which its wrongs should be righted, there will be no such thing as truth and reconciliation.

“Truth and reconciliation means reconciling past wrongs!” he says.

Osoyoos Indian Reserve was created in 1877.

‘Listen to the Wind’

Louie says the bottom line is chiefs and councils are elected to improve the standard of living of their people and provide better “cradle-to-grave” services and offer opportunity not dependency.

“A chief does not sit above the people but with the people,” he says. “In the Indian way, it is the majority who rule, and they do so through a governance system of honour, caring, sharing and respect.”

They do so through ceremony and ancestral teachings that need to come back to every leadership table on the Rez, he says.

“Sometimes, we, as Native people, have to look to our past in order to figure out how to go forward…,” says Louie.

And, sometimes, when it comes to major cultural and governance decisions, Rez leaders just need to step out of office, get back to nature and “listen to the wind,” he says.

“Anything we accomplish must include a strong sense of going back to time immemorial,” writes Louie. “Our language, our culture, our ceremonies, the land, the water and every living thing, plants and animals, are part of that legacy…”

Something tells us that Chief Louie’s “Rez Rules” will be remembered by future leaders for a long time to come.

“Rez Rules” is published by McClelland & Stewart, Penguin Random House Canada, and is available in bookstores and on Amazon.com

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow