Leaving no Native child behind: State proposal strengthens Indian Child Welfare Act

Special to the Times | Colleen Keane

Ambrose Ashley, who has made his home in Albuquerque, stands in front of the University of New Mexico. Ashley, an advocate for the homeless, runs AA meetings at the Albuquerque Indian Center.

By Colleen Keane

Special to the Times

ALBUQUERQUE

“I remember running into the open arms of my new family. Because of the (federal) Indian Child Welfare Act,” said Joseph Talachy, governor of Pojoaque Pueblo, at a Senate committee hearing on a state ICWA, “I was raised in a beneficial home.”

If he hadn’t been placed at Pojoaque, Talachy said he would have lost connection to his family, culture and the Tewa language.

Before the federal law was passed in 1978, Ambrose Ashley, 71, and his seven brothers, members of the Navajo Nation, didn’t have this critical protection.

When their mom had trouble caring for them alone after their dad died, they were abruptly removed from their home and cut off from their family, clan relations, culture and language.

He was 5 1/2 years old.

“They took my brothers and I in the middle of the night,” Ashley said. “It was a night-time kidnapping.”

Ashley and his younger brothers went to a non-Native home on the east side of town. The older brothers were placed at a mission home on the other side of town.

“It was traumatic,” he said. “The family was split up. We became strangers to each other.

“It left me feeling empty inside, invisible (on the outside,)” he added.

By 1978, one-third of the Native American child population had been placed in government and private foster and adoptive homes outside of their tribal communities.

Tribal leaders, parents and advocates demanded change resulting in the ICWA, which set down standards on how non-tribal courts and child welfare departments are to handle custody cases involving American Indian and Alaska Native children.

For example, when there is a need for placement, children are to be placed as a first priority with family members, secondly another family in the community and then a Native family from another tribe.

All the while, non-tribal government agencies actively help in this effort.

But over the years, it’s been an uphill battle.

“There are still a lot of problems around how the ICWA is complied with (or not),” said Donalyn Sarracino, the tribal liaison for the New Mexico Children, Youth and Families Department.

Challenges to the law

Most notably, she cited the Brackeen case in Texas. Anglo foster parents Jennifer and Chad Brackeen challenged the ICWA’s constitutionality in their effort to adopt a Diné/Cheyenne child.

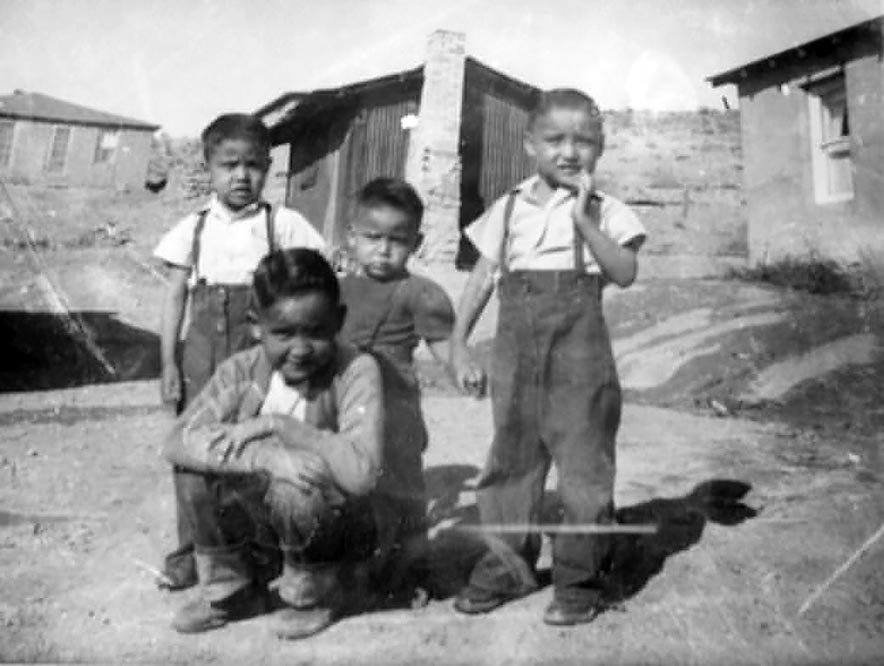

Courtesy photo

Ambrose Ashley’s family before the children were placed in different foster homes. Ambrose, center back, holds his brother Melvin’s hand as his brother Anthony stands to his left and his brother Eugene sits in front of them.

Sarracino, Acoma, said that because of challenges to the federal law, tribal leaders, parents and advocates are coming together once again for a state ICWA to strengthen and add protections to the federal law.

SB 278, sponsored by Sen. Benny Shendo, D-Jemez, has a companion bill in the House, HB 209, sponsored by Rep. Georgene Louis, D-Acoma.

At the Senate Indian, Rural and Cultural Affairs Committee meeting on Feb. 9, along with Talachy, representatives from the Choctaw Nation, Jicarilla Apache Nation, Navajo Nation, pueblos of Isleta, Tesuque, Santa Ana and Okay Owingeh, spokespeople from New Mexico Indian Affairs Department and Bold Futures, all expressed their support for SB 278.

The meeting was chaired by Sen. Shannon Pinto, Dine’, D-McKinley-San Juan.

Like the federal law, the proposed state ICWA honors the child’s family.

“Children fair better when they are raised by their family, keep their connection to their tribe where their culture and traditions are respected, taught their language, understand their clan and can participate in ceremonies,” said Judge Catherine Begaye, Diné, who presides over Bernalillo County’s (2nd judicial district) ICWA court. “That is critical.”

On a conference call with Begaye after the Senate committee hearing, she said the ICWA court, one of the few in the country, has made a big difference in reuniting Native children with their families and tribes.

“In our ICWA court program, 77 percent of children are placed with relatives,” she reported.

Currently, statewide there are 241 tribal youth in CYFD’s custody. More than half of the children are affiliated with the Navajo Nation, according to CYFD spokesperson Cliff Gilmore.

Major changes

One of the major ways the proposed state ICWA strengthens the federal bill is a provision giving tribes early notification when a child is in non-tribal court custody due to allegations of abuse or neglect.

“There are times when the child may not have to be removed,” said Jacqueline Yalch, Isleta, president of the New Mexico Tribal ICWA Consortium, on the same call with Begaye. “This provision would prevent the child from becoming an ICWA case.”

Yalch added that among other protections under the state law, the non-tribal government social workers are expected to clearly document what steps they’ve taken to reunite the child with tribe and family.

Ashley said his family never received any reunification support. During their six years in placement at the Gallup foster home, the brothers only saw their mom a few times and were isolated from their kin and clanship relations.

Sarracino said that the state ICWA bill was crafted by tribal leaders, parents and advocates with support from CYFD.

“We wanted to make sure we did this process and honored the tribal voice,” she said.

There have been four tribal consultations and regular workgroup meetings.

In the Senate Indian, Rural and Cultural Affairs Committee meeting, SB 278 passed with amendments regarding social worker efforts, documentation and child custody proceedings, to name some.

Sarracino said proposed amendments are still coming in from tribal leaders, parents and advocates.

“I hope this bill keeps other Native American children from going through what happened to my brothers and I,” said Ashley.

Talachy said the federal and state ICWA are critical protections for all tribes.

‘We are an endangered culture,” he said. “If we do not continue to protect our culture by protecting the children belonging to it, it will be lost in a few generations.”

ICWA is ‘gold standard’

As of Monday, SB 278 is waiting to be heard by the Senate Judiciary committee.

The session ends on March 20 at noon.

A Navajo Times story on Feb. 28, 2019, describing the Brackeen case features Ambrose Ashley and his brothers (“ICWA changed history, now court says it’s unconstitutional”).

Since the story was published, the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals overturned the lower Texas court decision, which had ruled in favor of the Brackeen’s.

“ICWA remains the gold standard of child welfare policy and practice,” said Sarah Kastelic, executive director of the National Indian Child Welfare Association. “It is in the best interest of Native children.”

A Marine Corps veteran, Ashley drew upon personal strength and heritage to overcome the trauma of foster care placement.

After his military service, he earned a social work degree, became an outspoken advocate for the homeless and runs AA groups at the Albuquerque Indian Center.

Information: nmlegis.gov, nicwa.org, narf.org and ncai.org

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow