Teacher turns to way of life for comfort and healing

GALLUP, N.M.

Diné language and culture teacher and COVID-19 survivor Albert Brent Chase says the many profound challenges, revelations and changes he experienced in 2020 are guiding his path of healing in 2021. “I, too, have suffered the grief and heartbreak that is ongoing with our people,” said Chase.

These include the loss of his mother, Maggie Joe, to COVID-19-related heart failure in October, and his sister Amanda Toney to an unexpected tragedy one week later, events that have altered his life forever. Chase’s own battle with COVID-19 left him bedridden in agonizing pain for over three weeks at home last summer.

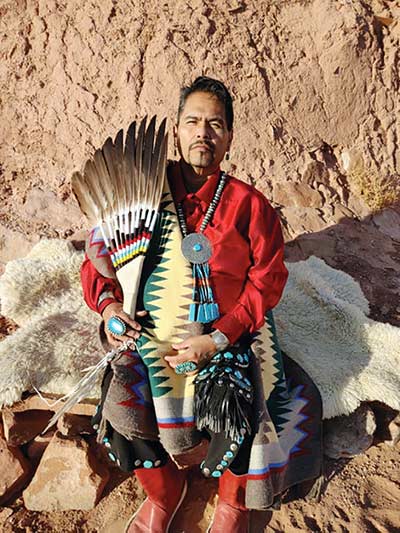

Courtesy photo | Garrick Yazzie

Seated by his hogan in Looking Horse, Arizona, Albert Brent Chase is dressed in traditional attire that he makes, including the necklace, feather fan, moccasins and gemstone-studded handbag.

“I did nothing but sleep because that was all the energy I had,” said Chase. “My strength was completely drawn.” By day 22 of COVID-19, Chase said he had “had it.”

“Because of the suffering, I was actually begging for this to be over with,” he said. After praying for relief, Chase fell asleep, and woke up to a rustling sound as the wind blew in his cornfield outside of his bedroom.

“As I looked to the window, I saw figurines of Corn People,” he said. “It scared me. One was pointing at me. I thought, oh, the Holy People came – I guess my prayer is answered. “They’re going to take me from my suffering,” Chase said. “But one spoke and said, ‘You’re going to survive, you’re going to get better.’” Chase dozed off and woke up the next morning, overwhelmed with emotion.

“I slept like I had never slept before,” he said. “As soon as I woke up that morning, I felt none of the pain I was suffering through the prior days.” As soon as Chase got his strength back, he walked out to the cornfield, where the corn stalks swayed above his head, and he sprinkled corn pollen on his body.

“I stood right in the middle of the cornfield, just bawling my head off, praying and thanking the Corn People for being beside me,” he said. “I thought, things will be good now. We’re all going to survive.” But soon thereafter his mom and his sister passed. The Corn People had also told him would have to be strong, said Chase.

“A lot of people are hurting right now,” he said. “I totally feel their pain. It’s so important to keep sharing and it’s OK to cry and feel that sadness because that’s part of the healing and we’re in this together.”

Life is precious

Chase says his spirituality is rooted in the cultural traditions and teachings of the elders who raised him from boyhood, including his grandmother Mae B. Chase, a weaver and herbalist, and his grandfather, Navajo Code Talker Frederick Chase.

“I felt their comfort and I was nurtured and loved by them,” he said. “A lot of them are gone and my heart breaks for those who are leaving us now.” Chase said his elders always taught him that life is precious.

“You live every day and you die once, that’s what my elders would say,” said Chase. “When you wake up, you give thanks to the Holy People and the Creator for giving you another day to experience the gift that was given to us.”

It’s important to take those teachings to heart, especially with something as detrimental as the COVID-19 pandemic, he said. “It brings you a new perspective and a more serious outlook,” he said.

Chase said many elders are striving to survive the pandemic. “Many of them still use the pollen to pray to live another day and thank the Holy Ones,” said Chase. “We have many of our people dying who would like to live many more years.”

Chase often reflects on the reasons the Corn People visited him. “The cornfield is our church, our sanctuary as Diné people,” he said. “The cornfield stories and the corn songs all hold our spiritual beliefs and the power of prayer and faith.”

Corn is also used as a teaching tool, he said. “Being that I am an instructor of our language and our culture, it makes sense,” he said. “Everything that I’m doing through language and teaching are tools of hope, strength and faith. Songs, prayers, and art are part of our healing entities so that’s what I’m turning to right now.”

‘We’re medicine’

Since last fall, Chase has redoubled his efforts to immerse himself in the Diné way of life and share language, culture, music and arts in new and innovative ways during the pandemic, including on social media. His group of Navajo language classes, including for students at Little Singer Community School, have moved to Zoom.

Chase says continuing his teaching has sustained him and given him strength to persevere through this time of monumental grief and uncertainty.

“Maybe by the grace of the Holy People and unfinished work that I’ve been assigned and was destined to do here on earth, I must have been spared,” he said. “I always think that there are reasons for things that happen. With that, I’ve been able to refocus on what I’m doing with my life.”

Founder of Diné Pollen Trail Cultural Consulting, which he runs with his nephew Garrick Yazzie, and leader of the Pollen Trail Dancers, who have performed all over the world for many years, Chase’s talents seem limitless. “I’ve always been told you should strive to be an extraordinary Navajo in all that you do so that you can pay it forward to those who need to be taught how to be extraordinary,” he said.

Chase is a traditional dancer, singer, storyteller, flute and piano player, weaver, basket maker, potter, hogan builder, sheepherder, farmer, and cook. He also makes traditional attire, including Diné hats, sashes, cuffs, handbags and jewelry. Some might call him a Renaissance man, but Chase says he’s just living the holistic way of life that was taught to him by his elders.

“Those are spiritual things that people took in as part of holistic healing,” he said. “I’m doing that to honor our way of life as well as my life because it makes me happy.” Chase says his online students appreciate his language classes because he ties in cultural teachings, storytelling and interactive art and music demonstrations.

The benefit of Zoom is that those who want to learn the language can do so from anywhere. “It gives us a chance to meet other people who are in the same boat and we learn together,” he said. Like many other artists and performing artists, Chase and his dance group lost many bookings at cultural events due to the pandemic.

His decision to redirect his energy to doing what he loves in a new way to prevent succumbing to grief is working, he said. “A lot of people are scared and feeling down about some of the tragedies we’re going through,” he said. “I’m going through it too, but if you can share something that’s healing, they feel good about it. We’re medicine for each other.”

‘Unseen monsters’

In considering the emergence of the pandemic, Chase said it’s been foretold that “unseen monsters” could return, and he has heard his elders speak of those things.

“It was also said that if we don’t abide by certain things and we begin to dishonor our way of life and our spirituality, our Hózhó will be coming off balance,” he said. “When we don’t sing our songs, when we don’t speak the sacred language that was given to communicate with the Holy People, we were going to pay a big price for it.

“I think we’re in those days,” said Chase. “Our shields are getting thinner and thinner from protecting us from these monsters.” He said those who were fortunate enough to learn Diné bizaad as their first language connected early on to the spirit and the power that can navigate them through life with the recognition of the sacredness in all things.

“The language is our shield,” he said. “It is our guide, our connection with realms unbeknown to other cultures. That’s why I’m so passionate to teach the language and to work with young people to try to regain that shield.” Chase believes that the power of prayer is also stronger in the Navajo language.

“Today, our prayers are different,” he said. “We leave a lot of important and sacred things out. We’re not feeding our own Holy People so they are not recognizing us. We’re not speaking to them in our language and pretty soon they’re not going to understand us anymore.”

It’s also important to continue to make offerings in accordance with the original instructions, he said. “When we take our pollen, our cornmeal, our offering, whether it be at the streams or a growing evergreen, those are our covenants that we make to the spiritual life, the spiritual beings and the Creator,” said Chase. “We call them out and we remember them so that they can take care of us.”

‘It brings Hózhó’

These days when Chase weaves at his loom, it brings precious memories of his childhood when he used to sit behind his mother’s loom playing with toys. “I could hear the pounding of my mother’s weaving,” he said. “It was such a comforting feeling to know that I was near those I dearly loved – my mother, my grandmother and my great grandmother.”

He says those memories are medicinal and therapeutic during these times. “It’s a healing place for me,” he said. “I feel the presence of the beautiful women who raised me.”

Cooking traditional foods also evokes warm remembrances for Chase. “It’s medicine that I’m partaking in to keep me strong and healthy,” he said. “The smell of that corn permeates throughout the house and brings me back to the hogan that I was raised in. I can still recreate it and those feelings take me through these tough times as I continue to grieve.”

Going to the corral and feeding his sheep, Chase says he also feels the presence of his elders who “put love into their work.”

“I feel they’re still around because I can see them through my flock,” he said. “The sheep, the cattle, represent our mother and our father and how they took care of us. They feed us and nurture us in the same way our parents did.” With newly sheared sheep wool, fluffy clouds turn into strings and carry the spirit of the weavings, said Chase. “You use them on your loom and see the designs, the expression of your love, your memory of your loved ones, and your life,” he said.

“Those strings that you weave tell a story for us. Then when someone sees it, it brings them Hózhó.”

Chase’s clans are Honághaanii, Naakaii diné’é, Tótsohnii and Nát’oh Dine’é.

Information: www.navajopollentrail.com or chasingwind@hotmail.com

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow