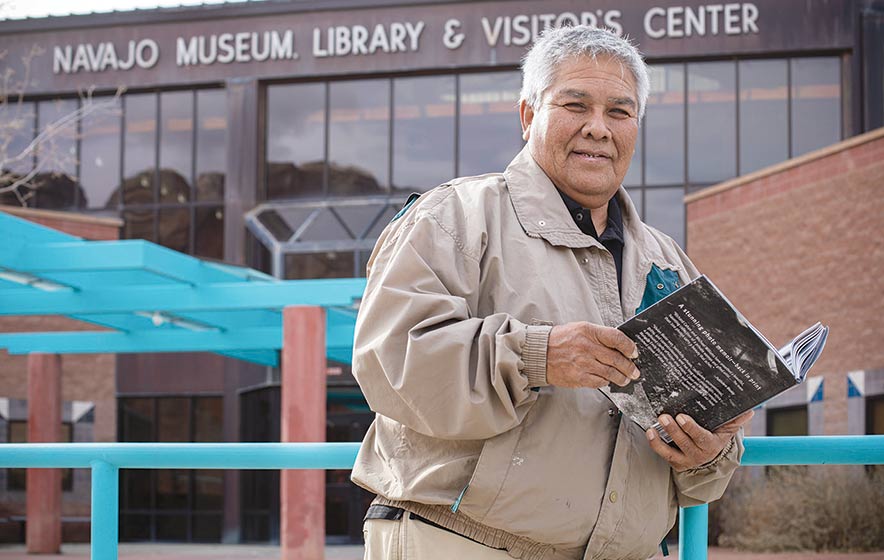

Nation’s top librarian turns the page on an epic chapter

Navajo Times | Sharon Chischilly

Navajo Nation Library Director Irving Nelson is planning to retire this year after more than 43 years with the tribal library.

WINDOW ROCK

If you were to make a list of the world’s most exciting careers, “librarian” probably wouldn’t even make the top 100. But in Irving Nelson’s 43-year stint with the Navajo Nation Library, he’s battled poisonous spiders, spent hours in an asbestos-ridden basement, walked miles in a blizzard and taken epic cross-country road trips just so you and the rest of the Navajo public can have something good to read.

Nelson, director of the Navajo Nation Library, is “trying” to retire at 61, but the COVID-related government closure is getting in the way of processing his paperwork. In a plot twist worthy of O. Henry, this lifelong bookworm is losing his eyesight to glaucoma and macular degeneration. “It’s getting so even driving home from Window Rock to Rock Springs is an adventure, especially if it’s dark,” he sighed.

But what a legacy he has left his people.

Lifelong love

Nelson, who is Kin Yaa’áanii born for Dziltl’ahnii, can’t remember a time he didn’t love books. As a student at John F. Kennedy Elementary, living in the Gallup dormitory, he eagerly awaited the weekly visit of English teacher Thomas Kirby, who would unlock the library and let the kids run rampant. Young Irving was one of his best customers, snatching up three or four books a week.

His favorites were the Louis L’Amour westerns. Books were his ticket out of the sometimes dreary dormitory life. “Reading was a way to transport myself to another world, another time, another dimension,” he recalled.

So it seemed only natural, when he turned 18 and graduated from Gallup High, to apply for a job driving the Navajo Nation’s only bookmobile. “We provided books to all 110 chapters,” Nelson recalled.

It was a big job, and all those miles must have taken a toll on the vehicle, because only about a year later, in January of 1978, the bookmobile broke down somewhere near Jeddito, Arizona. It was snowing hard and freezing cold. Nelson and his partner, the late Franklin Ayze, had to hitchhike back to Window Rock with only one jacket between them.

“We kept trading off wearing the jacket,” Nelson recalled with a chuckle. “We finally caught a ride in Steamboat. But it was in the back of a truck so we still couldn’t get warm.”

The bookmobile proved to be beyond repair. But Nelson had proved his mettle. They changed his title to “library technician,” and let him type the card catalog cards. (If you don’t know what a card catalog is, ask the nearest Baby Boomer. It’s all true.) “All I did was type all day long,” Nelson recalled.

Later the system graduated to microfiche (again, ask a Boomer), which was almost worse. “You’d have to search through hundreds of microfiche to find a title,” Nelson said. It’s starting to make sense that he’s losing his eyesight.

Promoted at 27

In 1986, then-library director Barbara Baum resigned. At the dewy age of 27, Nelson found himself the first Diné director of the Navajo Nation Library. And he’s been there ever since. “There” being a variety of places.

The first Navajo Nation Library was in the basement of the Window Rock Recreation Hall. It was infested with black widow spiders, and, perhaps more dangerous, crisscrossed with steam pipes wrapped in about a foot of asbestos. “It scares me to this day when I think about it,” he confessed.

There were only 5,000 volumes, divided into children’s literature, adult fiction, non-fiction, and along the back wall, an incipient collection of books by and about Native Americans.

The unpleasantness of the place notwithstanding, the Navajo people loved their library – maybe because it was the only one for miles. “We were always pretty busy,” Nelson recalled. In his off-hours, he took library science classes at the University of New Mexico-Gallup, trying to bring his education up to match his title.

Eventually, the research portion of the library was moved to the bottom floor of the Education Building, and in 1990, after the recreation hall was condemned, all the books were moved there. It was a lot more pleasant, but the collection was beginning to outgrow its space.

In 1992, construction started on the Navajo Nation Museum, which was planned to house the library as well. Nelson remembers the triumphant day the new library opened its doors: Halloween of 1997. “We had 11,000 books,” he said. “It was virtually empty.”

Filling the shelves

Nelson and his staff set out to fill the shelves. Using the tribe’s Native American Library Services grant, Nelson and a staffer would road-trip 36 hours straight to Washington, D.C., in a U-Haul to pick up the tribe’s allocation of books, turn around and tag-team another 24 hours to overnight in Oklahoma, then be back in Window Rock the next day.

Later they partnered with Goodwill Industries International in Annapolis, Maryland. “The very last trip I made, the other driver didn’t show up,” Nelson recalled. “I had to do the whole trip myself. I remember it was May and very hot … the U-Haul didn’t have air conditioning. But I was a young man then. I certainly wouldn’t try it now.”

Now the library partners with Reader to Reader in Hartford, Connecticut, and someone flies out, rents a van and brings the books back. It’s less heroic but much safer.

But the things Nelson is most proud of in his four-decade career don’t involve risking his personal safety. As with any nonprofit government entity, the real battles are for the funding to do the important work that laymen find too obscure to care about.

Points of pride

After begging the Navajo Nation Council for 20 years, Nelson finally obtained the $190,000 he needed to digitize the Office of Navajo Economic Opportunity Collection. These were film recordings taken in the 1960s of medicine men and other wisdom keepers. “The collection was 50 years old and I was terrified the tapes would disintegrate,” he said. Library staffers finally finished that project two weeks ago.

Nelson also digitized the entire 60 years of the Navajo Times, which involved tracking down the very first issue, which had gone missing. “We had two copies, both encased in Mylar and both encapsulated with a tracking tape, and they still walked off,” he said. “I finally located a digital copy.”

The fact that the library even still had copies of the Times was something of a coup. “At one time, I believe it was in 1979, I went before the Navajo Nation Council’s Advisory Committee to request funding to better preserve our collection of the Times,” he recalled. “They shooed me out the door — at that time the Times was running some unflattering articles about the Navajo Nation government.

“Before I left I was given a directive by one of the committee members to destroy all the library’s copies of the Times,” he said. “I said, ‘Yes sir,’ but I never did it. I knew I could lose my job if they found out, but I also knew that, as a librarian, I would never destroy an important historical document.”

Years later, the former committee member came into the library asking to see a certain issue of the Times.

“I said, ‘Sir, you directed me to get rid of the Navajo Times, and that’s what I did,’” Nelson recounted. “He got a sad face and started to walk out. I felt sorry for him and said, ‘Sir, come back here. I’m afraid I never followed your order.’

“Before he left he said, ‘I’m so glad you didn’t follow my order.’”

Playing a part

Libraries are beloved by those who read for pleasure and a necessity for students researching term papers, but we sometimes forget that they are also repositories for documents that provide the basis for important legal claims.

During the tribal government chaos of 1989, when the Navajo Nation Council put its chairman, Peter MacDonald, on administrative leave and he refused to step down, the Navajo Nation Department of Justice was frantically searching for documentation to see who held the authority in such a case.

“They looked at ASU, UofA, NAU, UNM, they couldn’t find anything,” Nelson recalled. “Finally they came in the library and I directed them to the Land Claims Collection.”

This was 32 filing cabinets of every legal document the tribe has to support its claim to its land base and sovereignty.

“From documents they found in the collection, they were able to determine that the ultimate authority resides with the Council,” Nelson said. “From there they were able to develop the three-branch government which laid out the division of power.

“I sincerely believe our library was instrumental in reforming the Navajo Nation government.” That collection remains to be digitized — a project for the next library director, Nelson says. But during his tenure, he has watched the library grow from 5,000 volumes in a musty basement to over 100,000 in an inviting, well-lit space, with a branch in Kayenta as well.

The next chapter

It’s a good time to hand over the reins, if the darned virus will let him. At the moment the building is closed for deep cleaning and, like millions of Americans, Nelson is working from home.

And what does the next chapter hold for Irving Nelson? The main thing he wants to do, as soon as it’s safe to travel, is get his wife back. She was visiting family in Canada when COVID hit and hasn’t been allowed to travel back to the States. “I haven’t seen her since January,” he lamented. “I miss her terribly.”

The man who spent most of his life between his job in Window Rock and his home 20 minutes away in Rock Springs now wants to see the world while his eyes are still able.

Of course, books will still be in his life. And no audiobooks for this lover of the printed word, at least not yet. “As long as I can keep enlarging the font on my Kindle,” Nelson professed, “I’ll keep reading.”

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow