PRC hearings: Northern Navajo’s economy hangs in the balance

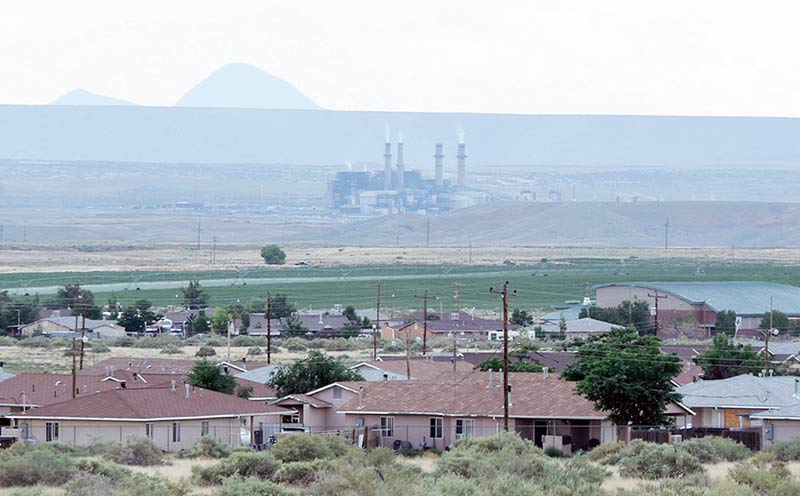

Navajo Times | File

The coal-fired San Juan Generating Station in Waterflow, New Mexico, pictured here, will close in 2022 if the New Mexico Public Regulatory Commission grants its permission. The PRC is currently hearing testimony on PNM's plan to close the plant and replace it with a gas-fired plant and/or renewable energy.

BOULDER, Colo.

Still stunned over the closure of the Navajo Generating Station, the Navajo Nation could soon be reeling over the closure of another power plant across the state line.

The San Juan Generating Station in Waterflow, New Mexico, which at its peak produced 1,848 megawatts of power for the city of Farmington and other customers, is scheduled to shut down in 2022 if the New Mexico Public Regulation Commission approves a proposal by the plant’s majority owner, PNM.

Public hearings on the shutdown started Monday and are scheduled to continue into next week.

While the impact to the Nation won’t be on the scale of the NGS closure, which will cost the Nation $20 to $30 million a year in revenue and more than 400 well paying jobs, it’s nonetheless a “major concern for the entire region,” said Navajo Nation Council Delegate Rickie Nez, who represents T’iis Tsoh Sikaad, Nenahnezaad, Upper Fruitland, Tsé Daa Kaan, Newcomb and San Juan chapters.

Between the power plant and the San Juan Coal Company, which operates the coal mine that supplies the plant, 189 Navajos hold well-paying jobs, according to PNM, the plant’s operating owner. A study commissioned by Four Corners Economic Development places the average salary for the plant and mine workers at $86,000 a year.

In addition, some 115 Navajo-owned contractors serve the plant and the mine, according to PNM, supplying yet more jobs.

Of the $7.4 million the plant pays annually in property taxes, $3.8 million goes to San Juan County and $3.6 million goes to the Central Consolidated School District, which comprises 14 schools on the Navajo Nation and three off-reservation schools.

Without that revenue, the district may have to turn to Kirtland, New Mexico, the lone off-reservation municipality in the district, to raise taxes to pay off its $37 million in outstanding bonds. Acting CCSD Superintendent Dave Goldtooth did not return two phone calls soliciting comment on how the district plans to cut costs or replace the revenue.

Prospective college students in the area can no longer count on the $115,000 in scholarships given annually by the plant and the mine.

The silver lining that didn’t appear with the NGS closure is state support for PNM’s weaning itself and northern New Mexico off coal.

New Mexico’s Energy Transition Act went into effect June 14, setting the ambitious goal of making New Mexico’s electrical grid 100 percent carbon-free by 2045.

The act, though, cushions the blow to coal-dependent San Juan County by allowing PNM to restructure its debt and add another $40 million for severance pay for its laid off employees along with job training, community projects and a displaced worker fund, to be paid by ratepayers over time (shareholders would forego future profits they would have received by keeping the plant open and merely recoup their investment).

PNM will also be required to locate at least some of its replacement power projects in CCSD’s territory to offset the property tax loss.

“The ETA is an amazing law,” said Raymond Sandoval, director of corporate communications for PNM. “The legislature listened to all the stakeholders and came up with something that, while we’ll all have to make some sacrifices, will allow us (PNM) to achieve our goal of transitioning away from coal and toward natural gas and renewables five years ahead of the state’s deadline.”

However, in a decision that surprised PNM, the Legislature and Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez, the state’s Public Regulation Commission on July 10 voted 4-1 to consider PNM’s plan to abandon the plant under an earlier docket that predated the ETA, putting the $40 million in employee and community transition funds at risk.

On Monday, Nez, New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham and the ETA’s sponsors petitioned the New Mexico Supreme Court to order the PRC to apply the ETA retroactively.

Meanwhile, the city of Farmington, which owns an 8.5 percent interest in one of the SJGS’s two remaining generators, has proceeded with plans to transfer its ownership to Enchant Energy, which in February floated a plan to keep the plant open by fitting it with carbon capture technology.

Enchant announced its selected contractors for the plan Tuesday, but PNM says the transfer of Farmington’s interest in the plant must be approved by a vote of the five partners in the plant, whether or not the others abandon the asset.

“Regardless of what happens to the plant, the partnership agreement does not go away,” argued PNM’s Sandoval. “It’s because the partners would still have liability.”

The tug-of-war over the plant has produced some strange bedfellows. The Santa Fe-based anti-climate-change group New Energy Economy is supporting Enchant’s proposal, while the Sierra Club has found itself allied with PNM in pushing the closure of the plant and its replacement with renewables and natural gas.

Much will hinge in the next two weeks as the PRC hears from citizens, including Navajo leaders, and decides whether to allow PNM to close the SJGS and whether the utility’s plan will be governed by the ETA.

And by the time this is all sorted out, the Navajo Nation will have to start thinking about yet another blow to its coal-fired economy. The contract between the Four Corners Power Plant and the Navajo Coal Mine, owned by the Navajo Transitional Energy Company, expires in 2031.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow