‘We want frybread!’: Emergency gig grows into cottage business

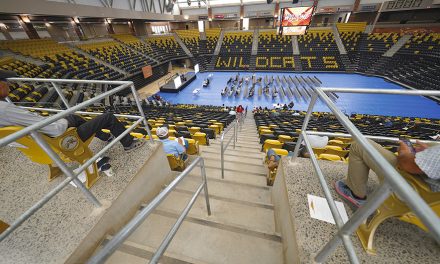

Courtesy of Valene Hatathlie

Sample of Val's Frybread

By Krista Allen

Special to the Times

TÓNANEESDIZÍ

It was Valene Hatathlie’s final semester of graduate school at Arizona State University, and she needed a little help paying her master’s program fees for spring 2020.

She did full-time study while her husband worked, paid the household expenses and helped pay for her tuition.

“I got to a point where I felt bad because my husband was paying all the bills and everything, and I wasn’t pitching in anywhere,” Hatathlie said. “I had a couple of (twill pattern) rugs that I wove. I made them into little purses, and I tried selling them.”

But her products weren’t selling and she wasn’t quite getting the price she expected – until one of her aunts invited her to sell the purses at the Native Art Market in Scottsdale.

Hatathlie said customers at the art market liked the purses but they couldn’t afford them.

Submitted

Valene Hatathlie

“It was kind of a drag,” Hatathlie said. “I just needed a little help. I just needed a little money to pay the program fee for the upcoming semester. I was almost done, and I had one more semester left. The finish line was just right there.”

While discussing the matter – and her career paths after graduation – with her aunt on Nov. 2, 2019, they overheard Denise Rosales’s conversation with someone about the need for a frybread vendor at the arts market.

“She (Rosales, Diné, the founder of Native Art Market) was like, ‘I need a frybread vendor. We need to find a frybread vendor,’” Hatathlie said. “I said (to her aunt), ‘Hey! I can do that! I heard her!’

“But I didn’t want to go over there and be rude and say, ‘Over here!’” she said. “So, I thought I’ll go find her at the end of the event and tell her I can be a frybread vendor and that I know how to make frybread.”

Anxious about approaching Rosales, who’s from Na’ní’á Hasání, to introduce herself and to ask for the frybread vending gig, Hatathlie hoped their first meeting would go smoothly.

Immediately after introducing herself and promoting her food service, Rosales accepted Hatathlie’s offer and showed her the spot where she would sell her frybread on alternate weekends after filing her food vendor’s, tax and business licenses with the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community.

Down to mom’s

“I went down to my mom’s (who lives right down the street from them in the Valley) house,” Hatathlie said. I told her, ‘Mom, I’m going to do this event. I need to borrow your tables, I need to borrow your canopy – your frybread pans.’”

Her mother, Theresa Hatathlie-Delmar, from Tsékǫ Hasání, accommodated her daughter and expressed support.

“Then my husband –– poor guy — I said, ‘We’re doing this. Be ready,’” she said. “He’s like, ‘What? Are you sure you have everything?’

“He went (through) a list with everything I needed,” Hatathlie explained. “When my sister came home from work, I said, ‘Guess what? We’re doing this next weekend.’ She was hyped.”

But the first sale at the art market was a “fail.”

“I sold one piece of frybread for $5,” Hatathlie said. “I’ve never heard of that but that was the pricing at that location based off of other vendors who sold there.

“But surprisingly people started coming around (on the weekends she and her family were there),” she said. “People were like, ‘We want frybread!’”

Hatathlie found it difficult to find a job after completing her bachelor’s degree in 2012, during an economic downturn.

“I moved back in with my parents for a whole year,” Hatathlie said. “I couldn’t find a job. I was volunteering at five different locations in Tuba City just doing my best, hoping that it will lead to a job.”

Her volunteer work led to 10 recommendation letters that she used to get a job at the Navajo Generating Station, where she went through the Operations and Maintenance I School before getting a job as a laborer.

“It was intense,” Hatathlie said about the O&M I School that is equated to a college course with classroom lecture and fieldwork followed by a nightly study group.

“It was the most studying I have ever done,” she said. “And at the end of (each) week you got tested and you had to pass. It was really intense, but I passed.”

Hatathlie worked at NGS for seven years until she heard talk about the plant shutting down at the end of 2019.

“Stuff got a little crazy at the power plant,” she said. “I figured this is my time. I need to move on to another chapter of life. I resigned from the plant in 2017 and I moved to Phoenix with my husband.

“It was a clear canvas that I could make into anything,” she said. “That’s how I looked at it. I had the opportunity to do something different, so I thought: I want a master’s degree.”

Master’s in business

Hatathlie wanted to study for a master’s in business at ASU but whenever she visited the W.P. Carey School of Business no one was ever available.

“For some reason, every time I went to go see (advisors at the school), the office was closed and there was nobody I could communicate with,” she said. “There was just a wall there and I was sitting in their office and I looked down beside the chair I was sitting in and I saw a pamphlet for the school of sustainability.”

After looking through the pamphlet, Hatathlie knew sustainability leadership was what she wanted to do and where she saw her future.

“That’s what I wanted to learn so I could make the biggest impact possible … being a businesswoman,” Hatathlie said. “I wanted to shift my focus to that.”

Hatathlie finished her master’s degree in May 2020. Now, she makes sure she’s always serving “the best frybread” to customers.

“They want them golden brown; they want it really fluffy,” Hatathlie explained. “But sometimes they don’t come out that way.”

Hatathlie learned how to make frybread when she was a child, alongside her cousin sisters and brothers, from her aunties and grandmother. She and her sisters and brothers made bread nearly every day either at home or at a ceremony during the summertime.

“And having to cook for a group of people, there’s always going to be tortilla bread or frybread, so that’s where we picked up on it,” Hatathlie said. “It’s just something that always had to be done.

“Tortilla bread went with breakfast, lunch and dinner,” she said, “especially when people came around my grandparents’ house to visit. My grandparents would say, ‘Come on, you’ve got to cook. You already know you got to cook for them. You already know you have to entertain them, so go make some dough.’

“To us, it was normal,” she said. “It was like everybody knows how to make dough – even the boys. My grandmother taught us all how to make food and if we didn’t want to make food, she always told us, ‘You need to learn this. This is a life skill.’”

That skill turned into a business, said Hatathlie.

Val’s Frybread

Customers say they enjoy Valene’s – or Val’s – frybread.

“It’s like the customers named us and everything just evolved,” she said. “‘This is Val’s Frybread.’ People comment on our frybread and it has kind of just stuck in our heads.”

When a customer joked he would like for Hatathlie to send him a box of frybread mix, the idea for a homemade frybread mix was born.

And that’s when the real work began with help from her brother-in-law, Justin Gilbert, owner of Kuvua Design.

“So I said, let’s jump on that,” Hatathlie explained. “It was kind of a big investment starting off, getting all the packages printed and everything; finding out what we needed; the labeling and stuff, the nutritional facts.

“We had to do the research on our own,” she said. “So we got the packages one day and we started. We had to figure out the science behind it, the measurements behind it.”

Hatathlie and her team learned that making either frybread or tortilla is a two-to-one ratio. For instance, two cups of Val’s Frybread mix plus one cup water is needed to make a good dough.

“And just letting the dough sit for 30 minutes before you roll it,” Hatathlie said. “When it’s done rising, then you would have to roll the dough out and sit for at least another 10 to 30 minutes and then you can flop it out and put it in the grease. And then we had to figure out the whole situation with the grease.

“If you’re indoors making frybread or if you’re outdoors making frybread, what’s the temperature range?” she asked. “So we had to buy all these gadgets to figure it out – measures, temperatures and stuff. It’s pretty interesting.

“So, finally after we figured that out, we had to write the instructions out,” she said. “We ran it through a lot of different people to test and then we submitted everything to the company that was going to be printing the bags.”

Hatathlie ordered 600 for the first run. When the packaging arrived, she and her team had to fill them one by one, after which she created a website to sell them, as well as selling them at her frybread stand.

Hatathlie said she employs Native college students not only help with extra money but also to give them business experience.

“A lot of the customers tell me, the non-Natives, they tell me they love frybread but there’s nowhere to get it,” Hatathlie said. “You have to go somewhere else to get it.

“And that’s kind of true,” she said. “You do have to go onto a (Native nation) to find the frybread. They’ll say, ‘We need frybread!’”

Hatathlie said she recommends putting honey or salt on frybread, which the non-Natives like.

“Native ladies, they’ll say, ‘One frybread with honey and salt!’” she said. “Then there are some Native ladies (who say), ‘We want one frybread extra crispy! With honey and salt!’

“I’ll say, ‘Yep, coming right up!’” Hatathlie said. “The popular one is frybread and honey.”

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow