‘Buried alive’: Leonard Peltier, Native American activist imprisoned for nearly half a century over FBI killings, awaits last chance parole hearing

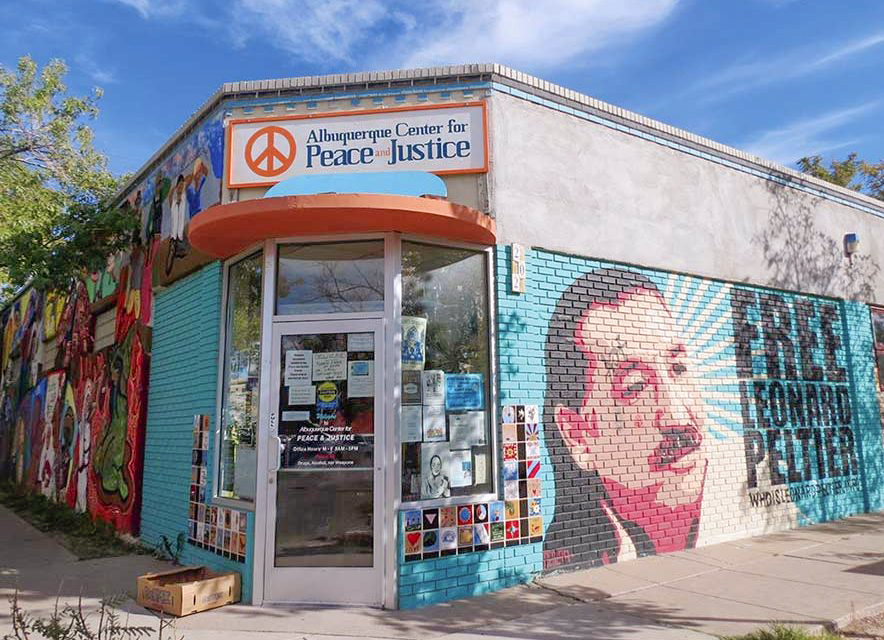

Courtesy photo | Joanna Keane Lopez

The Albuquerque Peace and Justice Center has advocated for Leonard Peltier’s release from prison for many years. This mural was created about 10 years ago, in this 2021 file photo.

By Melanie Cissone

Special to the Times

NEW YORK CITY – In less than a week, the fate of long-imprisoned Native American activist Leonard Peltier (Turtle Mountain Chippewa) will be known throughout Indian Country, among the world’s Indigenous people, and around the globe.

Peltier, who turns eighty years old in September, has been incarcerated for nearly 50 years. In fact, he’s the longest-held Indigenous prisoner in U.S. history. Peltier is serving two consecutive life sentences for the murders of FBI agents Jack R. Coler and Ronald A. Williams. On June 10 he appeared for the third and likely last time before a hearing examiner for the U.S. Parole Commission to appeal for clemency.

Peltier’s attorney, Kevin Sharp, wrote at the end of that long day, “Hearing ended at 5:30 EDT. Decision in 21 days.”

Attorneys Kevin Sharp, a former federal judge, Jenipher Jones, a “movement attorney,” and Moira “Mo” Meltzer-Cohen represent Peltier. From three separate law firms in three different states, the co-counselors have based arguments for their client’s parole on a few factors: the arbitrariness of his detention length given his age, health, and safety in a maximum-security environment and the inhumane lack of medical attention to the 79-year-old’s failing health.

Beyond these, Meltzer-Cohen, who gave closing arguments, included remarks which were a matter of “the record” or procedural. Including making mention of previous parole hearings, the hearing examiner heard letters for his release and in opposition to Peltier’s release, he heard oral testimony by victims’ advocates or family members, an FBI representative spoke, the U.S. attorney sent a representative, and proponent witnesses to parole Peltier spoke including a physician who had examined him and a representative from Indian Country.

Peltier can barely walk. He needs a wheelchair but uses a walker. He must make do talking and eating with the few remaining teeth he has. He suffers from diabetes, high blood pressure, the effects of a previously suffered stroke, and complications from jaw surgery. He was diagnosed with a potentially fatal abdominal aortic aneurysm and runs the risk of COVID-19 reinfection. The spread of the virus among prison populations is six times that of the general population, and in his current fragile state another bout of Covid might kill him.

Peltier is Inmate #89637-12 at United States Penitentiary Coleman 1, a maximum-security prison with some 1,456 male inmates located in Sumter County, Florida. Over the last five decades, he’s been moved to and from other federal penitentiaries, Leavenworth included. Peltier has been at Coleman 1 for more than ten years. At no time has he been close to his North Dakota home, making it a challenge for family members to visit.

Peltier has several children with different women. Lisa, his oldest, was born in 1965 to Peltier and Sandra Martinez, his wife for a short time. Chauncey, 58, and a younger sister, Cheryl, were born to Peltier and Joanne Lohnes. Marquetta Shields-Peltier, 50, and Wahacanka Paul Shields-Peltier, who passed away at 41 in 2016, were the product of Peltier’s union with Audrey Shields. Kathy Peltier, 48, is Peltier’s youngest daughter whose mother is Ann Begay. Born after her father had already been detained, she continues to be outspoken about her father’s release.

Board president of Justice Peltier and retired hod carrier and rigger, Chauncey Peltier remembers his father, “I spent a lot of time with him before he went inside. I actually traveled around with him quite a bit.”

It hasn’t been easy for Peltier’s family. “The first twenty years of Leonard’s incarceration was pretty rough for his family,” Chauncey said. None of Peltier’s children were able to attend his June 10 hearing because of the limited number of witnesses permitted.

Part of a larger prison complex in central Florida, Coleman 1 is the highest security detention center in the state. Even at a frail 79-years-old, Peltier is subjected to frequent lockdowns. “When you are imprisoned,” Peltier recently wrote, “when you are in a box, a large coffin, day in and day out, year in and year out, it never ends. It’s like you are buried alive.”

A formal request by The Navajo Times for a telephone interview with Peltier was denied by the Bureau of Prisons. The media contact at Coleman 1 wrote, “Your request to interview Mr. Peltier has been reviewed. Unfortunately, we will not be able to accommodate your request at this time. The request has been denied.”

On June 26, 1975, on the Pine Ridge Reservation in southwestern South Dakota, a pair of FBI agents and a devotee of the American Indian Movement were killed in a bloody shootout. All three victims were in their twenties: agents Jack Coler, 28, and Ronald Williams, 27, as well as Joseph B. Stuntz (Coeur d’Alene), 23. Both Coler and Stuntz were married and each the father of two sons.

Each driving an unmarked car and dressed in plain clothes, Coler and Williams were on the reservation that morning to serve a warrant for the arrest of Jimmy Eagle, who was accused of assault with a deadly weapon and stealing cowboy boots on the reservation. The FBI agents identified a car they believed was occupied by Eagle and went looking for it.

The Rapid City, South Dakota, FBI resident city office––120 miles away from Pine Ridge—routinely investigated felonies on the reservation including robbery, kidnapping, assaults, rapes, and murders.

Testimony in Peltier’s 1977 trial indicate that FBI agents dispatched on cases at Pine Ridge usually operated two radios from their cars; one was an FBI radio that enabled both car-to-car transmission and communication with the Rapid City office, and the other was a state radio with channels that allowed agents to speak to state highway patrol, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and the Pine Ridge Police. Far from their home office, agents assigned to Pine Ridge investigations would stay in motels in Rushville or Gordon, Nebraska.

According to FBI case files, Peltier, then 30, was at Pine Ridge with a group from AIM, staying at the Jumping Bull’s family ranch with other movement followers who had traveled from a ten-day AIM convention in Farmington, New Mexico. Coler and Williams were unaware that Peltier had an existing warrant out for his arrest for Unlawful Flight to Avoid Prosecution for the attempted murder of an off-duty Milwaukee, Wisconsin, police officer.

Agents found themselves uninvited strangers in a place and at a time when then Chairman Dick Wilson’s militia was exerting self-imposed authority reservation-wide. At one point the vehicles stopped, a stand-off ensued and, inexorably and tragically, a shootout occurred.

Peltier has never denied exchanging long-range gunfire with the FBI agents. In a 1992 “60 Minutes” interview that coincided with the release of the documentary film “Incident at Oglala,” Peltier told Steve Kroft about a third vehicle that happened upon the scene at the fateful moment. “Well, there’s two individuals in this red pickup, which drove down there,” said Peltier. “And the passenger got out. That’s about as far as I can go.”

Kroft asked if he knew who they were, to which Peltier answered, “Yes.”

Asked if he would reveal their identities, Peltier said, “No. No.”

Kroft pressed further, to no avail. “I can’t do that, Steve,” Peltier said. “I can’t do that. I can’t. I’m not a rat, I’m not a snitch, I’m not an informant first of all. Second of all, we sincerely believed what we were struggling for, and, to turn against one of your own and start pointing fingers, in my heart, in my mind, would be treason.”

“Why treason?” asked Kroft quizzically at the use of a word to describe an act of criminal behavior that’s usually a betrayal of one’s country.

“Because they’re (the FBI) the enemy,” Peltier says, “They’ve been the one that’s oppressed my people, nearly exterminated my people. I lived it. I experienced it. I witnessed it. So, nobody can tell me any different.”

On the heels of AIM’s fifth annual convention attended by hundreds representing Indian Nations from throughout North America, a press release details the group’s adoptions. Under “Cultural Racism, America’s Longest Undeclared War,” the eight-page announcement enumerates six action steps, “When these crimes are committed against our people, the communities must be dealt with immediately by these actions,” and the sixth of these said, “Immediate retaliation against these communities by whatever actions are necessary.”

Ten days after the June 16 close of the AIM convention, Peltier was at Pine Ridge Reservation. Peltier had a rifle. Peltier exchanged fire with Coler and Williams. Three men’s lives were taken and Peltier fled South Dakota and eventually the United States.

Four men were indicted in connection with the murders of William and Coler. Among them was Jimmy Eagle, whose charges were dropped for insufficient evidence. In July 1976, Dino Butler and Bob Robideau went to trial in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Arguing self-defense, Butler and Robideau were found not guilty.

Meantime, Peltier was a fugitive from justice and on the FBI’s Most Wanted list. On the lam and sited in northern California in November 1975, he crossed the Canadian border on foot, thinking he would never get a fair trial. Sheltered at the Smallboy Camp, a traditional splinter group of the four Cree Nations of Maskwacis in the Rocky Mountains of the British Columbia province in Canada, Peltier was arrested by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police on Feb. 6, 1976. Detained in Vancouver, Peltier was extradited to the U.S. in May 1976.

A blood-stained contextual history

Wounded Knee Creek (Čhaŋkpé Ópi Wakpála) winds through the southwest corner of South Dakota, where the badlands meet the Great Plains. Amber waves of grain sway in the wind, showcasing the spectacular geographic beauty there. Beneath the surface, however, the stunning landscape disguises a blood-stained region.

The 100-mile tributary of the White River lies about the same distance southeast of Mount Rushmore. There, the likenesses of four U.S. presidents are carved into the sacred Black Hills, otherwise known as the Paha Sapa. The Lakota say Paha Sapa is “the heart of everything that is.”

South of the national memorial and monument therein, and two dozen miles through a foothill pass from Oglala in East Shannon, South Dakota, is the site of the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre. It was here that 250 Lakota civilians, many of them unarmed men and innocent women and children, were wounded or killed by the U.S. Army. In a senseless standoff for fear of the Ghost Dance, the 7th Cavalry also suffered injuries and losses numbering 64.

Fast forward 82 years. In 1973, more bloodshed occurred in the region during the Wounded Knee Occupation. From Feb. 27 to May 8 of that year, 200 AIM followers joined forces with dissident Oglala Lakota “traditionalists” to occupy the village of Wounded Knee for 71 days.

Invited by those wishing to govern in customary ways, AIM joined the opposition to the thuggish, corrupt, and nepotistic reign of Oglala Lakota Chairman Richard “Dick” Wilson and his private armed force of Guardians of the Oglala Nations, whose apt acronym was GOONs.

This unrest was unfolding as the Lakota Sioux were suing the U.S. government for violating the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, demanding a full return of the Black Hills land taken in 1877. Oglala occupiers also wanted to divorce themselves from a meddling Bureau of Indian Affairs. A year earlier, in 1972, AIM marched on Washington, D.C., in what was called the “Trail of Broken Treaties” and occupied the BIA headquarters.

The 1973-armed siege, sometimes called The Second Wounded Knee, resulted in the deaths of Frank Clearwater (Cherokee) and Lawrence “Buddy” Lamont (Oglala); the wounding and partial paralysis of U.S. Marshall Lloyd Grimm; and the disappearance of black civil rights activist and journalist Ray Robinson. Law enforcement numbered more than 1,000 and there was talk of paramilitary assaults prior to the ultimate May 8th stand down. Much like the murderous Reign of Terror of the Osage, Pine Ridge Reservation was experiencing a reign of terror of its own. Few were aware that the U.S. government, as has been asserted by renowned former FBI Special Agent Coleen Rowley, was in collusion with the likes of Dick Wilson.

The backdrop

Tensions remained high at Pine Ridge after the 1974 re-election of Wilson, whose opponent, Russell Means, was the first national director of AIM. Despite an investigation by the U.S. Civil Rights Commission alleging election fraud and declaring the runoff against Means an invalid election, a federal court upheld Wilson’s re-election.

It’s impossible to understand Leonard Peltier’s story and his motivation for joining AIM absent a glance into the tenor and tone of the era.

In the post-WWII era of the late 1960s and early 1970s, a Cold War timeframe in which anti-communism was the U.S. primary foreign policy objective, activism among the disenfranchised and liberation movements took shape. The American Indian Movement was founded, the Black Panther Party formed. It was a time of peaceful anti-Vietnam activism—Make Love Not War. Gay rights came to the fore, the women’s movement grew, the Equal Rights Amendment passed, and Title IX was introduced. A little sunlight began to shine on causes that had long lurked in the shadows.

Even before its Washington, D.C., occupation of the BIA and the Wounded Creek Occupation, AIM had occupied Alcatraz in 1969, had staged a protest in Boston and took over the replica Mayflower II ship on Thanksgiving Day 1970, and it had taken over Mount Rushmore briefly in 1971.

In a 2023 interview with Nick Estes of Red Nation podcast, 24-year FBI veteran Coleen Rowley, described the palpable 1970s climate that served as a backdrop leading up to the incident at Oglala. She also weaves in to the conversation theories on institutional groupthink.

Rowley is that rare G-man (or G-woman) whose name you may have heard. In 2002 Time magazine named her its Person of the Year for her role as a 9/11 whistleblower. Rowley and fellow agents in her Minneapolis office had warned their superiors of an impending terrorist attack prior to 9/11. Afterward, Rowley testified before the 9/11 Commission in Washington about the inherent failures in the FBI in terms of how information travels up the ladder.

Speaking to Estes in 2023, Rowley said, “Nothing’s perfect. You start to see little flaws. One thing after another…systemic policies that make good people do dumb or bad things.”

Rowley and another retired FBI Special Agent, Jack Ryan, support Leonard Peltier’s release. Sadly, Ryan lost his pension in 1987. He was 10 months short of eligibility when he was let go for refusing to investigate non-violent activists like many of the people who would have been in the groups named above.

Adding color and context to the state of affairs during Special Agent Rowley’s days in the Minneapolis FBI field office, the podcast host reminded Red Nation listeners that most of the AIM surveillance and investigations were launched from there. It was also the founding hometown and headquarters of the American Indian Movement.

Rowley told Estes that, as part of her 1981 FBI training school, “There were lectures that re-viewed the FBI’s version of the facts of the Leonard Peltier case…in gory detail…with slides…more than once.” She suggested it seemed an unusual training alternative on those days when students couldn’t do shooting practice because of sleet or snow.

It was also how Rowley first became familiar with Peltier and AIM.

Two years into her FBI career, Rowley gained access to stacks of files the National Lawyers Guild received as a result of a Freedom of Information Act request. An attorney herself, she combed through the FBI’s counterintelligence program (COINTELPRO) files to see just who the agency had been spying on.

With 300 categories of crime, as it turned out, everyone from mobsters to popular folk singers were surveilled. “Spying on someone like Pete Seeger,” Rowley said, “or communists meeting in a house, you drove by and got their license plates.”

While Seeger had been a member of the Communist Party in the 1940s, the popular folk singer known for such hits as “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” was watched by the FBI for decades. The FBI kept hundreds of files on Seeger. Can you imagine how many were kept about AIM?

“It was easy work,” she says. “Post and floats,” were what the non-violent surveillance assignments were called. Such surveillance was exactly what Jack Ryan opposed.

Rowley spoke of “the banality of evil,” a phrase coined by historian Hannah Arendt. She talked about the power and peril of group loyalty, citing the “FBI family” or the “Blue Code of Silence” among police officers as examples. She explained how groupthink pervades police work and the military and that it can blind well-intended loyalists from objectivity and truthfulness. Therefore, it became acceptable to monitor peace activists and groups like AIM.

Peltier’s case, she added, is out of sync with other murder prosecutions. Rowley’s point gets to the arbitrary arbitrariness of convictions and sentencing. Wrongly or rightly convicted of murder, Rowley contrasts Peltier to FBI agent Mark Putnam, who murdered his informant girlfriend, stowed her body in the trunk of his car, and served 10 years of a 16-year sentence. Whereas Peltier, as a reminder, is serving consecutive life sentences and has already done nearly half a century.

All three legal teams are up against constitutional indiscretions, prosecutorial inconsistencies, in addition to old-law incarceration versus new-law detention. Those convicted of crimes before 1987 are rarely granted compassionate release.

Amnesty International refers to Peltier as a “political prisoner.”

The designation “political prisoner” connotes malfeasance on the part of the U.S. government. It’s most commonly used to describe people being punished for their beliefs or threat to the government. Imprisonment for the expression of political beliefs is rare in the United States because free speech and expression are well-established law.

The USA branch of Amnesty International sent representatives to Peltier’s 1977 trial and to evidentiary hearings in 1978, 1983, 1984, 1985, and 1991. Amnesty International made a plea in 1995 to then U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno to conduct a special executive review.

In a moving letter to the Parole Commission recognizing all who lost their lives that day, Amnesty International USA Executive Director Paul O’Brien wrote on March 27, 2024:

“We are not alone in asking you to use your powers to grant parole to Leonard Peltier. We join Tribal Nations, Tribal Leaders, Indigenous Peoples, Members of Congress, former FBI Agents, Nobel Peace Prize Laureates and even the former U.S. Attorney, James Reynolds, whose office handled Leonard Peltier’s prosecution and appeal, in urging his release. Reynolds wrote in 2021, ‘in my opinion, to continue to imprison Mr. Peltier any longer, knowing all that we know now, would serve only to continue the broken relationship between Native Americans and the government.’”

Arbitrary arbitrariness

Kevin Sharp points out that judicial review of cases was different in 1977 than it is today.

Ruled inadmissible at the time, the jury in Peltier’s trial never heard about the relevant underlying tensions between factions at Pine Ridge Reservation leading up to AIM followers being invited there. There was hidden exculpatory evidence, which normally would have been cause for a new trial. One member of the jury admitted a prejudice against Native Americans and was, nonetheless, permitted to serve as a juror in Peltier’s case. The jury didn’t know Myrtle Poor Bear had falsified her witness affidavit. They also didn’t know that ballistic experts could not match shell casings in the trunk of the shot-at FBI agent’s car to Peltier’s rifle. Further, misconduct on the part of the FBI never prompted another trial. Rebuking former FBI Director Louis Freeh for opposing executive clemency, former Attorney General Janet Reno under President Bill Clinton never called to question the prosecutorial misconduct in Peltier’s case.

Peltier’s parole rests solely in the hands of President Joe Biden’s Office of the Pardon Attorney and the recommendation to the Parole Commission by the hearing examiner in attendance at the June 10 hearing. Normally a five-seat body, there are only two commissioners now, one a Bush appointee and the other an Obama appointee. Both have been serving for decades.

Peltier’s fate has been down this road before. Years can pass between the time a petition is made and when it’s heard. He petitioned for the commutation of his sentence in 1989 but it was “administratively closed.” Peltier petitioned again and was denied in 1993 and, in 2016, he petitioned and was denied on Jan. 18, 2017, by President Barack Obama. The current petition in front of the U.S. Parole Commission was pending its 2021 filing. Peltier, his representatives, witnesses for and against his release were heard on June 10.

What’s the most expeditious get-out-of-jail card? Confess and show remorse.

He has demonstrated a weightiness for the three lives lost that day, but Peltier won’t say he did something he says he didn’t do, even if it could return him to his family and home. Mo Meltzer Cohen said after the hearing, “His refusal to admit to something he did not do shouldn’t be taken as some kind of perverse recalcitrance, but as an excess of rigid honesty.”

“He has issued a full-throated expression of remorse for his part,” she said.

Whether Leonard Peltier is released, not paroled, or possibly remanded to a less restrictive prison remains to be seen. We’ll know by July 1. Currently, Peltier is and has been a cause célèbre for the humane treatment of aging pre-1987 federal parolees, for Native American rights, and for prosecutorial, judicial, and prison reform. If his parole is denied and he dies in prison, Peltier will surely rise to the ranks of martyrdom.

“My life is an extended agony. I feel like I’ve lived a lifetime in prison already. And maybe I have. But I’m prepared to live thousands more for my people. If my imprisonment does nothing more than educate an unknowing and uncaring public about the terrible conditions Native Americans and all Indigenous people around the world continue to endure, then my suffering has had—and continues to have—a purpose. My people’s struggle to survive inspires my own struggle to survive. Each of us must be a survivor,” from Peltier’s 1999 personal testament, “Prison Writings: My Life is My Sun Dance.”

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow