Chapter Series: Hemmed in by history

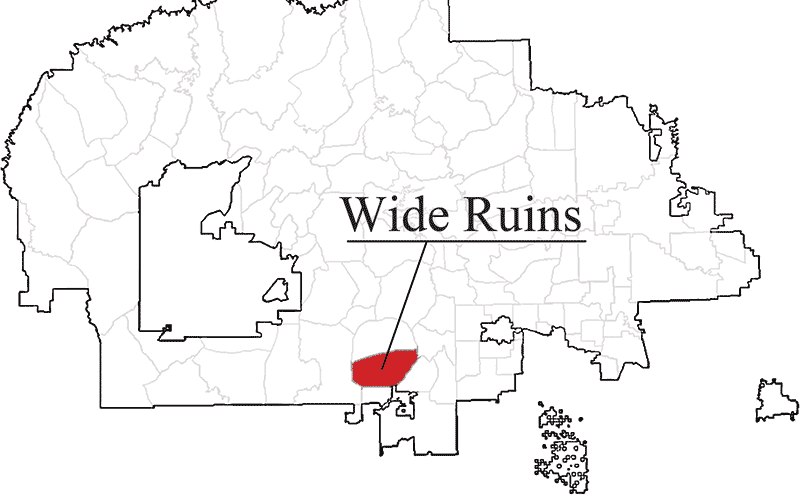

Wide Ruins locator map showing the chapter in the south-central portion of the Navajo Nation. (Times staff map.)

Wide Ruins’ future is threatened by its past

(Editor’s note: In an effort to chronicle the beauty and diversity of the Navajo Nation, as well as its issues, the Navajo Times has committed to visiting all 110 chapters in alphabetical order. This is the 110th and final installment in the series. Some information for this series is taken from the publication ‘Chapter Images’ by Larry Rodgers. For the full series, view the Chapter Series archive here.)

WIDE RUINS, Ariz.

The original Wide Ruins School is on the National Register of Historic Places. (Times photo – Cindy Yurth)

If you pull off U.S. 191 onto this pleasant, rolling plateau blanketed with pygmy forest, you will discover not one but three sets of ruins.

Careful eyes can pick out ancient walls protruding from the sand here and there — the outlines of a butterfly-shaped Anasazi greathouse wider than Chaco Canyon’s Pueblo Bonito.

Built into one of those walls, with stones pirated from the prehistoric construction, are the remains of a Turn-of-the-Century trading post, overgrown with giant cottonwoods.

A stone’s throw from that is a modern pre-fab metal building, vandalized and sprayed with graffiti.

Together, they tell the story of why this beautiful and very progressive chapter, former stomping grounds of the great Annie Wauneka, is stranded in time.

Let’s start with the Anasazi, who were here in the late 1200s, toward the end of their era, and probably numbered considerably more than Wide Ruins’ present population of 1,095. In addition to the greathouse, innumerable smaller structures dot the area along the big wash that bisects the chapter. You almost literally cannot walk around here without stepping on a pottery shard.

Henry Nelson, 81, shows off a picture of his grandson on his cell phone. Nelson was pulled out school at age 6, but his daughter is in college. (Times photo – Cindy Yurth)

‘They’re everywhere,’ said the chapter’s exasperated vice president, Louise Nelson. And when it comes to hanging onto their land, the Ancient Ones are worse than any grazing permit holder.

‘You wouldn’t believe the amount of time that goes into archeological clearances here,’ Nelson said. ‘If we want to build, we have to do it on land we already have.”

But that’s problematic too. Because in this chapter, where the trading post dates to 1895 and the school to 1930, even the Navajo-era buildings are historic. Both the trading post and the old stone original school are on the National Register of Historic Places, which means they can’t be razed.

When the trading post burned in 1986, the chapter used the insurance money to buy the pre-fab metal building, which it hastily erected right beside the old store. Until the National Park Service got wind of it.

‘We never got to use the building,’ lamented Nelson. ‘They won’t even let us go in there to move it.”

‘Even to clear brush,’ added Community Services Coordinator Dorothy Baldwin, ‘they won’t allow it.’

Historic yet progressive

This is too bad, because this is a progressive chapter with big ideas. It’s on the cusp of being certified, and between the major archeological site and beautiful Antelope Lake, it could have a thriving tourist industry.

It’s a land that produced some strong early leaders, like Black Rock Gaddy, Hastiin Yazhi, Boniface Bonney and Joe Yellowhorse.

In those days, Wide Ruins was known as a wealthy land. People planted big fields of corn and squash, and there were large ranches like the Lynch Ranch that employed 50 men.

‘We were like a food bank,’ said Baldwin.

‘If people needed something, they knew to come here,’ explained Nelson. ‘Wide Ruins was never greedy. When they saw someone in need, they would offer them something. And there was never any talk of charging.”

Back then, this sleepy plateau was bustling with activity.

‘Wagons were running here and there,’ Nelson said. ‘On butchering day, it wouldn’t be one or two cows, it would be 30 or 40. Everyone was weaving, even if they had to make a loom from the branch of a live tree.”

To this day, Wide Ruins rugs, with their subtle natural dyes and pleasing horizontal patterns, are prized by collectors.

The trading post hosted activities and acted as an employment agency for men like Nelson’s brother Henry, who was pulled out of school at 6 to help his mother herd sheep and never went back.

‘The Santa Fe Railroad and other employers would go to the trader and say, ‘I need some men,” explained Henry Nelson in Navajo, ‘and the trader would tell the men about it.’

Social life

Social life revolved around the trading post and the Mennonite Mission, where the women wore their hair in buns and kerchiefs almost like Navajos.

‘They were gentle people,’ recalled Louise Nelson. ‘We always looked forward to Christmas, when they would bring us candy, toys and hand-made quilts. They were the original Toys for Tots.”

To the north, St. Anne’s Catholic Mission in Klagetoh was also a boon to the community.

‘The priest and the nun were almost like our doctors,’ Nelson recalled. ‘They would bring aspirin, cough medicine and diarrhea medicine.”

To the east, St. Michael’s Mission kept birth and baptismal records and provided an alternative to the Wide Ruins BIA School, which was notorious even among the BIA schools.

‘The matron was just mean,’ recalled Nelson, who attended there. ‘All the staff walked around with paddles hanging from their belts, just looking for an excuse to use them. A few words in Navajo would get your knuckles rapped with a yardstick.”

Nelson, for one, would not mind seeing the old school razed, historic or not.

New school coming

After years of slowly drifting toward the top of the list and then being knocked down for one reason or another, the 1960s-era community school that’s in use now will be replaced starting this year. The replacement represents the lobbying work of several successive school boards, some of which Henry Nelson was on.

Next in line are power and water line extensions, the paving of the Wide Ruins Loop Road and the updating of the rural addressing system (Wide Ruins is one of the few chapters that already has street signs).

As far as economic development, the chapter is toying with the idea of a hemp farm, which got a firm thumbs down at the first chapter meeting at which is was brought up.

‘Our elderlies need to be educated,’ said Nelson. ‘They associate hemp with marijuana. They were asking, ‘What happens if it’s airborne? Are we all going to get drunk?”

If the chapter can convince the Park Service to let it move its metal building, it would love to have a store, gas station and Laundromat — presently most people drive 66 miles to Gallup to do their shopping.

‘We’re just waiting to be certified,’ said Nelson. ‘Then we can write proposals to some millionaires: ‘Come in and invest in us!”

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow