Shiprock attendees: Keep uranium statement Navajo

SHIPROCK

The main thing about the Navajo Nation’s position statement on uranium cleanup should be that it’s from a Navajo perspective.

That was the consensus of several attendees at the first public hearing on the subject, held at Diné College’s Shiprock campus Thursday. “From the traditional Diné perspective, we regard the earth as a living entity,” said Shiprock Chapter President Duane “Chili” Yazzie. “Every kind of illness, harm, injury that exists in the earth, there’s always been a remedy.

Navajo Times | Cindy Yurth

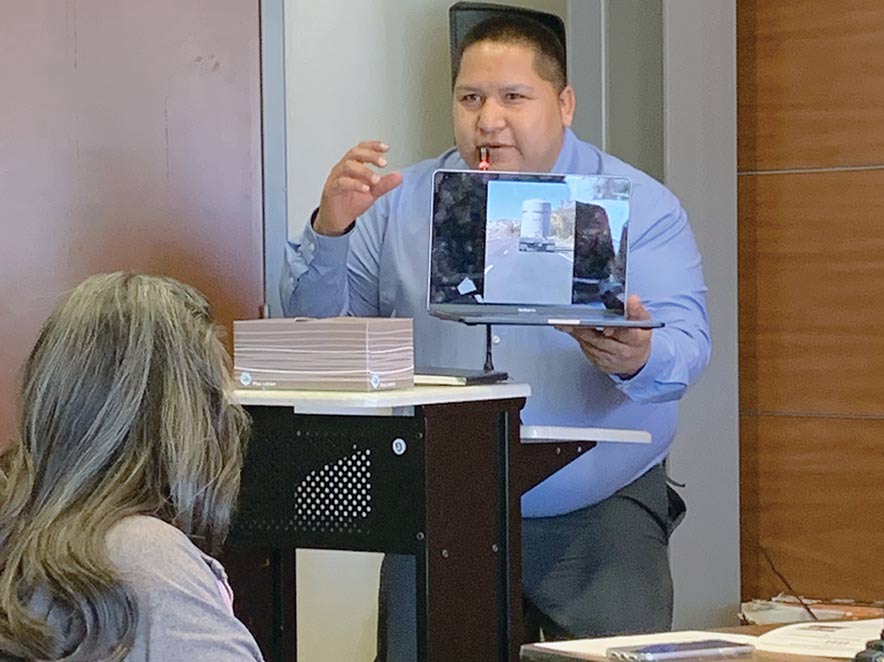

Joe Hernandez, who identified himself as the president of the Shiprock Head Start parents’ association, shows photos of trucks carrying unidentified substances coming through Shiprock. Hernandez said at the recent hearing on uranium that some of the containers had the nuclear symbol on them, and he was concerned radioactive waste might be being transported through Shiprock.

“Is there a ceremony that can be invoked that can neutralize the harm that emanates from uranium?” he asked. “If there is such a remedy we should look for it.”

Botanist and geologist Arnold Clifford said that, from his research, the appropriate ceremonies would be the Earth Way and the Ground Way, but he didn’t think there were any surviving practitioners.

“The spirituality is where we are all coming from,” agreed Hazel Tohe of the Diné Center for Research and Evaluation. “It (uranium) has got a spirit.”

While some of the 50-plus people at the meeting wanted the statement to press for more compensation for victims of uranium-related illnesses, Tohe, whose husband, environmental activist Robert Tohe, recently succumbed to stomach cancer, opined that “no money will ever suffice to save us from cancer.

“Let the (position paper) plan something out that’s productive for the community,” she continued. “We have to have a community ceremony, a community Blessing Way. We have to reflect on our inherent responsibility and initiate our relationship with the ground, with the air and with all our relations. We have to draw on Fundamental Law. It’s just not a backdrop.”

San Juan County (New Mexico) Commissioner and former Navajo Nation Council delegate GloJean Todacheene, who had to have her thyroid gland removed because of what she suspects was uranium exposure, suggested the position paper include five things: analysis and assessment, a plan of action, any necessary designs for the action plan, closing any remaining uranium mines that are still open, and monitoring the plan’s results, because “things break down.”

Personal experience

Several people described their own or a family member’s experience with uranium-related illnesses, including various cancers, heart problems, respiratory illnesses and birth defects in the children of uranium workers. Deficiencies in the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act came up, including the fact that it doesn’t cover post-1971 uranium workers, and that miners’ family members who ended up with cancer aren’t covered.

Stella Tsosie, secretary-treasurer at Red Valley Chapter, described the “village” that grew up around the uranium mine her father worked at, with children playing in the rubble and women cooking on fire rings made from uranium ore. Her father built the family’s first home out of rock from the mine, she said, and though the house later tested positive for radon and the government gave her family a new home, the old one is still standing.

“Who is going to demolish my house?” asked Tsosie. “I feel like doing it myself, but I might get in trouble dumping it somewhere.”

Nikki Begay, whose uranium worker father died of cancer, said she works for the Navajo Birth Cohort Study and the study is finding high levels of uranium in the blood and urine of some Navajo newborns even though the uranium mines have been closed for decades.

Like several people at the hearing, Begay mentioned the five-year plan by a consortium of federal agencies and the Navajo Environmental Protection Agency to address uranium contamination on the Nation and wondered why the Nation was just getting around to a position statement, considering the five years ended in 2018.

Tommy Yazzie expressed the feelings of many in the room when he said, “Let’s do something about it today. Let’s not just talk, let’s take action.”

While the six members of the Nabik’íyáti’ Committee who attended the hearing agreed that progress on the issue has been painfully slow, Delegate Eugenia Charles-Newton, who represents Shiprock, said it’s important the Nation present a “united front” when lobbying in Washington.

She pointed out that the Council has not been idle. “We have gone on several trips to D.C. to advocate for uranium workers,” she noted. “We have been bringing this issue to the forefront.” Delegate Amber Crotty said it’s important for the Council to hear directly from impacted communities before developing its position.

Evap pond

Chili Yazzie and others had questioned why, if the Nation was intent on letting the communities take the lead, President Jonathan Nez had issued a statement supporting the replacement of the liner of an evaporation pond at the old Shiprock uranium mill site while the community had not yet taken a position on the disposition of the pond.

Charles-Newton, who had attended several Department of Energy hearings on the pond, said she didn’t know how that position had been arrived at and agreed that the affected community should be consulted on any tribal position, which is the purpose of the series of hearings on the uranium paper.

Yazzie also wanted to know why the pond cleanup didn’t fall under the recent $44 million Tronox settlement, since that company had owned the mill. Tribal attorney Harrison Karr explained that the U.S. DOE is responsible for the Shiprock mill site, while the Tronox settlement went to the Navajo Nation EPA for use by that agency’s superfund program to deal with resource contamination.

Delegate Daniel Tso said his main frustration with the uranium cleanup process is how little a say the Navajo Nation seems to have. “We got a $1.7 billion settlement,” he said. “When there’s a settlement, it usually goes to the people who filed the suit. Instead they gave it to the USEPA. They (EPA) gave $300 million to this outfit that didn’t really have a good reputation.”

Tetra Tech, the contractor for the first phase of the uranium cleanup, is currently embroiled in a lawsuit filed by the U.S. government over alleged fraud in the cleanup of an old Navy shipyard in San Francisco that is now a housing development.

’638 the cleanup?

Speaker Seth Damon said the tribe had approached USEPA about the possibility of a memorandum of understanding and an eventual PL 93-638 contract for the cleanup.

“They flat-out said no,” he said, adding that the Council would continue to press for that option. But community member Kyle Jim questioned why the tribe has to work with the federal government at all.

“My concern is to be aware that this system we are upholding is the federal government that oppresses us,” he said. “We need to get back to k’e. We have to think amongst ourselves and network with other indigenous people.”

Hank McCabe, a consultant for Energy Fuels Resources — which owns the country’s last licensed uranium mill near Blanding, Utah — suggested the Nation transport the tailings from all the abandoned mines to the mill, where the tribe could profit from any extractable uranium or vanadium remaining in the waste and the rest could be “put away in our certified cells.”

“We can take 660,000 tons tomorrow morning,” he said. “We’re ready to go, man, that’s what we do.”

Another public hearing on the tribe’s uranium position was held Friday in Crownpoint (see accompanying story). The next two hearings will be March 13 in Chinle and March 14 in Tuba City, locations to be announced. Dates have yet to be set for hearings in Nahata Dziil and Oljato.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow